Zora Neale Hurston, Diaspora, and the Memory of Hurricanes

September has become the month to remember disasters. Apart from September 11, there is the memory of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and its devastating impact on New Orleans. And now the new hurricane season has spawned new memories of Harvey and Irma and the disasters left in their wake. As a daughter of Caribbean parents with family and friends scattered throughout the islands and southern states, I have significant memories of hurricanes. There is Hurricane David in 1979 that threatened my time in St. Croix with my family but mercifully passed us by (while damaging nearby Puerto Rico). And how could I forget Hurricane Hugo in 1989, which destroyed my grandmother’s house in Nevis and blew the roof off my aunt’s house in the U.S. Virgin Islands? Living in upstate New York, I felt, but was spared the effects of Hurricanes Irene and Sandy back to back.

“July, stand by/August, look out – you must!/September, remember/October, all over.” So goes the saying, and climate change may have extended the season. Such moments recall provocative conversations with my mother, who suggests that hurricane winds are more than the trade winds forming off the coast of Africa. What if they have absorbed the collective rage of our fallen ancestors from the slave ships? Anyone who has heard such winds would not doubt that spirits are still reeling from pain. The hurricanes of the Atlantic certainly follow in the path of the Middle Passage, beginning at the west African coast and making their way to the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, or the eastern coast of North America.

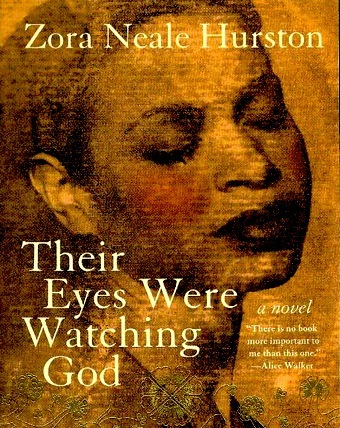

Whether interpreted as “nature” or “rage,” the winds – or spirits – demand our listening and our memory. It is with this current hurricane season in mind that I have revisited Zora Neale Hurston‘s Their Eyes Were Watching God. A novel told from the perspective of its light-skinned heroine Janie Crawford, who walks away from two husbands before falling in love with the younger Tea Cake, it is as much an ecological tale as it is love story with its documentation of the 1928 hurricane devastating the Lake Okeechobee area and leaving over 2,000 dead – most of whom were black migrant workers. As Janie survives controlling marriages, a passionate but also controlling lover, and a deadly storm before she reaches self-actualization, we are treated to the genius of Hurston, who allegedly wrote this novel in seven weeks while embarking on anthropological research in Haiti before it was published in 1937.

Having left behind a tumultuous love affair with a younger man, Hurston’s Guggenheim-fellowship-supported trip gave her respite from a man who demanded she give up her career to devote to their relationship. This personal tale is interwoven with memories of Hurston’s own experience of a 1929 hurricane in the Bahamas, as well as her interviews with survivors of the Okeechobee hurricane in Florida. Their Eyes Were Watching God thus intersects the geopolitical memories of Florida, Haiti, the Bahamas, and New York (the site for Hurston’s love affair), the hurricane an apt metaphor for tensions and contentions shaping black women’s lives and their own Diasporic consciousness.

In Sister Citizen, Melissa Harris-Perry connects Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God to the black female Katrina survivors, arguing that “post-Katrina New Orleans, as read through the lens of Hurston’s novel, is a place to begin taking seriously the idea that black women’s experiences act as a democratic litmus test for the nation.” Harris-Perry further contends that it was the pain and vulnerability of black women that shifted the national conversation from black male looters and rapists to suffering black mothers, daughters, and children. Such political legibility extends back to a legacy of black women writers like Hurston. Asserting a similar argument, Keith Cartwright suggests Hurston’s role – based on her participation in a Vodou ceremony in New Orleans as an Oya initiate – is akin to a literary Oya-Yansa, Vodou goddess of the storms. 1 In rewriting the history of Florida’s hurricane, Hurston conjures the storm – both literally and figuratively – as a transformative and passionate force.

Widening the Diasporic lens, Claire Tancons traces this 1928 Okeechobee hurricane back to its initial impact on the island of Guadeloupe, based on the memories of that storm shared by her grandmother, as well as its later manifestation as Hurricane Felipe on the island of Puerto Rico. Locating the historical “women of the whirlwind,” Tancons suggests their representation “is never too assured, or so secured, and is always on the verge of going with the wind.” 2

In other words, whether we look to the literary role of Hurston-as-Oya or the political symbol of black womanhood and their precarity, what would it mean to locate a “Black Atlantic” or “Diaspora” not on solid ground or even the expansive Atlantic, but within the stormy winds? What gets irrevocably transformed, what is salvaged, and what are the remnants of memory and our livelihood?

In revisiting Hurston, who devoted her anthropological and literary works to making legible the Black Diaspora and to validating its cultural expressions, linguistics, and aesthetics, her interests remained as mobile as the hurricane winds, and as committed to tracing the tracks of our Diasporic footsteps. She simply conjured a proto-feminist tale in the process of remembering an unforgettable storm.

- K. Cartwright, “‘To Walk with the Storm’: Oya as the Transformative “I” of Zora Neale Hurston’s Afro-Atlantic Callings,” American Literature 78, no. 4 (December 2006): 741-767. ↩

- C. Tancons, “Women in the Whirlwind: Withholding Guadeloupe’s Archipelagic History,” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 16, no. 3 39 (November 2012): 143-165. ↩