On the New York Young Lords: An Interview with Darrel Wanzer-Serrano

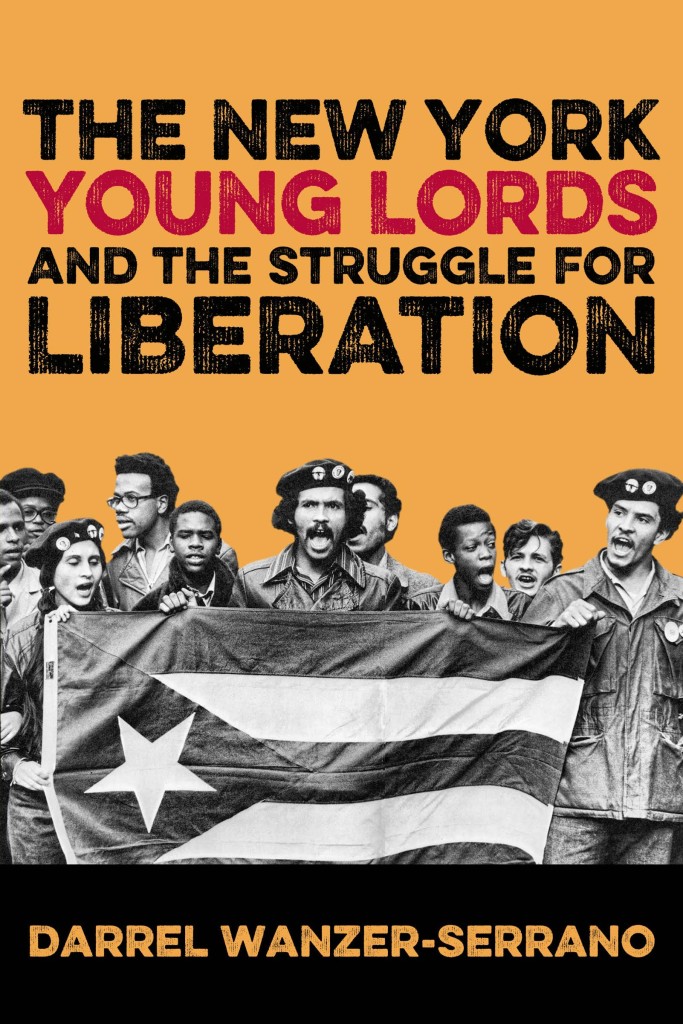

This month, I interviewed Dr. Darrel Wanzer-Serrano, the author of an exciting new book entitled The New York Young Lords and the Struggle for Liberation (Temple University Press, 2015). An original study, Wanzer-Serrano’s book is the first full-length scholarly work on the history of the New York Young Lords. Drawing on a wealth of primary sources including oral histories and memoirs, Darrel Wanzer-Serrano rescues the organization from historical obscurity and makes a compelling argument for its continued relevance in contemporary Latino/a politics.

Dr. Darrel Wanzer-Serrano is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication Studies at the University of Iowa. He was born and raised in western Washington state, where he remained until graduate school. He attended the University of Puget Sound for a B.A. in the Department of Communication Studies (1999), where he was an active participant on the policy debate team. After four years there, he made the difficult decision to leave the Pacific Northwest and pursue graduate studies at Indiana University in the (then newly formed) Department of Communication and Culture. At Indiana, Darrel received an M.A. in Rhetoric and Public Culture (2001). In 2007, he received his Ph.D. in Rhetoric and Public Culture under the directorship of John Louis Lucaites. His first book, The Young Lords: A Reader, was published by New York University Press in 2010. He joined the faculty at the University of Iowa in 2012, where he teaches graduate and undergraduate courses in rhetoric, cultural studies, critical theories of race/ethnicity, coloniality, and Latino/a studies; and he has a research focus on the same topics. You can follow Darrel on Twitter @DoctorDWS.

***

Keisha N. Blain: Tell us more about the developments that led to the writing of this fascinating new book. What inspired and/or motivated you to write about the New York Young Lords?

Darrel Wanzer-Serrano: I write about this a little bit in the introduction, rather than a preface, because I think it’s crucial for Latin@ studies scholars to be clear about the epistemic location from which they speak and write. My journey to the Young Lords and this project began in graduate school, long after I thought I knew who I was as a scholar and had finally settled into the epistemic zeitgeist of critical communication studies. As I went through my coursework, my department made some new hires that helped shift my perspectives and began leading me down another path. First, we hired Yeidy Rivero, an amazing media scholar and the first Puerto Rican professor I had ever met. Although I never had the chance to take a course with her, she and I began informally discussing Puerto Rican history, politics, culture, and so on; and she provided me with some reading list suggestions to start me on the path of ascertaining a bit more about my own ethno-racial background. Discovering more about Puerto Rico’s colonial history led me to also talk with another professor in my department, Roopali Mukherjee, about postcolonial theory and the politics of race/racialization. These conversations with Rivero and Mukherjee remained in the background— side work that I investigated half-heartedly for my own personal edification rather than scholarly pursuits. Second, we hired Phaedra Pezzullo, an abundantly smart and savvy feminist and environmental rhetorician, who offered her first graduate course on “feminist rhetoric” during what was supposed to be my last semester of coursework in the spring term of 2003.

Pezzullo’s class became a key moment in my personal and intellectual development. About a third of the way through the semester, we met to discuss final project ideas. We had been reading some feminist scholarship on autoethnography and performative writing, and knowing that I wanted to tackle the ideas I first broached with Rivero, Pezzullo offered the idea of letting me do a kind of autoethnographic piece related to my Puerto Rican heritage. Never before had a teacher or professor ever encouraged me to research something so intimately tied to who I was. Knowing virtually nothing and unsure where to begin, I started by turning to Roberto Santiago’s edited collection Boricuas: Influential Puerto Rican Writings— An Anthology. Eagerly opening the pages of the book, I experienced multiple revelations. First, reading Sandra María Esteves‘s “Here,” I got poetry for the first time . . . and I wept. Her words spoke (and continue to speak) to me on a level that I struggle to verbalize. Second, I ran across a small piece by Felipe Luciano, excerpted from the Young Lords’ book Palante: Young Lords Party, and was entranced. Identifying with his experiences surrounding a lack of access to language (i.e., not being fluent in Spanish), culture, history, and more, I became excited and hurriedly began researching the New York Young Lords as best as I could from Bloomington, Indiana. The experience was transformative both on an intellectual level and on a personal one, as I became Boricua (Rivero would affectionately refer to me as a “born-again Boricua”) through my research and writing. While I was born a Puerto Rican in Washington State, it took three professors (all of whom are women, two of whom are women of color) to jumpstart the process of getting me to think from a position rooted in Puerto Ricanness and latinidad.

Once I really got into the archival research and began conducting oral histories, I became even more inspired by what I was finding. Here was an organization — the first uniquely Nuyorican radical organization of the post-McCarthy era — that had a tremendous impact on diasporic politics, art, and culture, yet there was very little scholarly attention paid to the group. So one motivation became recovery and recuperation of the history of the Young Lords. A second motivation, which came later, was to explicate the unique ways that the Young Lords can contribute to a more grounded understanding of decoloniality, both in the realms of activism and scholarship. Decolonial scholars have done well to lay out the theoretical foundations of decoloniality, but but work remains to be done to explain what it looks in the world and what it looks like as a scholarly critical perspective. For me, the Young Lords seemed like the perfect vehicle to accomplish those theoretical/critical goals.

Blain: In broad strokes, how would you describe the New York Young Lords? What were their primary goals and political strategies? What were the movement’s ideological goals?

Blain: In broad strokes, how would you describe the New York Young Lords? What were their primary goals and political strategies? What were the movement’s ideological goals?

Wanzer-Serrano: During their brief tenure (1969–1976), the New York Young Lords were a revolutionary nationalist, antiracist, antisexist group who advanced a complex political program featuring support for the liberation of all Puerto Ricans (on the island and in the United States), the broader liberation of all Third World people, equality for women, U.S. demilitarization, leftist political education, redistributive justice, and other programs as these fit into their ecumenical ideology. Their activism took many forms. They gave speeches, held rallies, taught political education courses out of their community offices, and produced a newspaper and radio program (both called Palante) that articulated their vision of democratic egalitarianism, anticolonialism, and socialist redistribution. They started numerous community initiatives such as the lead poisoning and tuberculosis testing programs, childcare for working mothers, and meal programs for poor children. They also engaged in acts of civil disobedience such as the garbage offensive, two separate takeovers of an East Harlem church (which they renamed the “ People’s Church” each time), sit-ins and disruptions at a local hospital that the city had condemned, and support of acts of civil unrest sponsored by other groups (e.g., Black Panther Party and student groups). In all, they engaged in what they believed were strategically and tactically sound actions to advance their cause and transform their people. Operating in a colonial borderland that was mapped onto their spaces, bodies, and minds, the Young Lords advanced decolonial sensibilities in El Barrio and beyond.

Their goals and ideology were complex. On the one hand, they initiated a number of programs that were very practical with clear instrumental goals. For example, their lead poisoning testing program, which I open the book discussing, was a very practical action that set out to test kids in tenements to determine if they were being poisoned. New York City had the test kits, but they weren’t using them to actually help curtail what was becoming an epidemic. So the Young Lords staged a sit-in to acquire the test kits and then worked with medical students to administer the tests. On the other hand, they had broader goals that were based in their Thirteen Point Program and Platform, which laid out their ideological and practical commitments. Every time they did an action, even something as protean as offering free coats, they linked it to their Program and Platform. Furthermore, their ideology — although calling for socialism — was quite ecumenical insofar as they drew inspiration from seemingly contradictory sources (e.g., quoting Jefferson and Castro) to assemble a set of perspectives rooted in the invention of what some in the group called “compatibility.” Eschewing the resolution of contradictions, such compatibility allowed them to engage in complicitous critiques in the Puerto Rican tradition of jibería. In their final phase of development as the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization, however, they lost their flexibility and endorsed an orthodoxy rooted in Marx, Engels, Stalin, Lenin, and Mao.

Blain: How were the New York Young Lords similar to and/or different from other political groups during the Black Power era? How were they similar to and/or different from other chapters of the organization in cities like Chicago?

Wanzer-Serrano: I think they were probably most similar to the Black Panthers for a couple of reasons. First, they had some similar intellectual roots insofar as both groups drew from radical Black thought. For example, both the Panthers and the Lords drew implicitly and explicitly from the writings of Frantz Fanon. Beyond the comparison, the Young Lords consistently operated in coalition with the Black Panthers from their beginnings in Chicago. In fact, the original Chicago chapter formed a partnership with the Black Panthers and the Young Patriots (a radical white organization), which was called the Rainbow Coalition (not to be confused with Jesse Jackson’s group). And in New York, the two groups regularly worked in cooperation with one another, even coming to each other’s aid in times of crisis. All of that said, the Young Lords did not merely parrot the Black Panthers; they drew some inspiration and worked together, but the Young Lords were not simply the Puerto Rican version of the Black Panthers. They had their own issues and community needs, some of which overlapped of course, and their own genealogy of thought anchored in Puerto Rican and other Latin American revolutionaries.

The connection to Chicago and its affiliated branches is a bit more complicated. The Young Lords were originally a street gang in Chicago, beginning in the 1950s. In 1968, while doing a bid in jail, Chicago Young Lords leader Jose “Cha Cha” Jimenez had a political conversion after reading Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Thomas Merton. Upon his release, he transformed the gang into a street political organization. When the New York Young Lords formed in July 1969, it was as an official chapter of the Chicago group. As their relationship developed, however, the two main branches began to grow apart. There are various, complicated reasons for the eventual separation — reasons that will differ depending on whether you talk to someone from the Chicago group or the New York group — but the bottom line is that they had different strengths and different aspirations. In May 1970, the New York group changed their name to the Young Lords Party and continued to operate in coalition with Chicago, but took with them the organization’s national media program and much of the attention. Ultimately, I believe the New York group (and its branches in Newark, Philadelphia, etc.) was better organized and more media savvy than Chicago and its affiliates.

Blain: Tell us more about the process of conducting research for the book. What did you find most surprising and/or exciting about conducting research for this book? What kinds of sources did you find most useful?

Blain: Tell us more about the process of conducting research for the book. What did you find most surprising and/or exciting about conducting research for this book? What kinds of sources did you find most useful?

Wanzer-Serrano: I began by acquiring copies of the Young Lords’ writings that were available through interlibrary loan: their book, Palante: Young Lords Party; issues of their Palante newspaper available on microfilm; mass media news coverage of the group; published testimonios of leaders; and documentary films. There was little scholarship on the Young Lords at the time, but I gathered the handful of book chapters and journal articles that were available. Quickly, I realized the need to travel to New York City to conduct research and made arrangements to spend some time in the archives and collections of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College. Surrounding that trip, I tracked down former Young Lords (leaders and cadre) whom I could interview. As word spread that I was not yet another person looking to merely capitalize off the legacy of the Young Lords, more doors were opened. Over the course of about three years, from 2004 to 2006, I conducted about two dozen oral histories of former members and allies. Across multiple visits, I collected materials from additional archives—New York University’s Tamiment Library, the New York Public Library, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, private collections—including images, ephemera (e.g., flyers and buttons), and recordings of their radio program and other radio and television appearances. Some of this textual and imagistic material made it into an earlier collection of primary sources titled The Young Lords: A Reader (NYU Press, 2010). Other materials, however, have sat in my archive only to be reencountered as I was preparing the manuscript for this book.

One of the things I found most surprising and frustrating was the lack of any single, good collection. Most of the members have long ago lost the materials they once had, including the all-too-familiar story of a parent or friend throwing them out when moving or cleaning an attic. What was most exciting and useful, however, were the stories from former Young Lords themselves. Not only did those interviews help fill in gaps in the historical record, but they provided texture that could never have been captured by archival documents. Hearing and seeing people tell their stories allowed me to observe the lived dimension of their experiences—the ways in which memories of their time in the Lords were inscribed onto their bodies. In Chapter 3, I draw heavily from oral histories with women members so that I might operate in the interstices of the archive and the repertoire. Oral histories, according to Maylei Blackwell, function as “a hybrid that fits somewhere in between the archive and the repertoire, depending on how the narrator narrates, how the listener listens, and how the researcher wields the apparatus of objectivity that records or captures this performance.” In drawing from these oral performances of embodied memory, I rely heavily on the women’s own words and act as much as possible as a facilitator bringing their story of change over time to the reader. As a listener of their stories, my praxis is undergirded by a decolonial ethic of love and grants an epistemic priority to the voices of these women. At the same time, I recognize how problematic that role may be for me, so I try to deal with that explicitly in the book. At the end of the day, though, the conversations I had with the Young Lords women and men were the most rewarding part of the research process.

Blain: How would you compare and contrast women’s roles and responsibilities with men in the New York Young Lords? How were the experiences, concerns, and priorities of men different from the women in your study?

Blain: How would you compare and contrast women’s roles and responsibilities with men in the New York Young Lords? How were the experiences, concerns, and priorities of men different from the women in your study?

Wanzer-Serrano: I think the longest chapter of the book is the one on women in the Young Lords, in part because the issue is so complex and in part because there’s so much to say since it’s the aspect of their history that has been covered the least. And that’s actually one of the points I open the chapter with: the absence of this issue from many of the “official” (male) stories of the group. The absence of a markedly gendered struggle from our collective memory, however, should probably not be surprising. As Marianne Hirsch and Valerie Smith argue, “gender is an inescapable dimension of differential power relations, and cultural memory is always about the distribution of and contested claims to power. What a culture remembers and what it chooses to forget are intricately bound up with issues of power and hegemony, and thus with gender.” Accordingly, when the history of an organization is baptized in a sexist revolutionary politics and recounted officially from within a cultural frame marked by machismo, that frame shapes what is remembered and forgotten. Those memories, then, have an extended impact on our contemporary public discourse.

Initially, women in the organization were given what they called “shit work”—invisible labor in the private sphere and behind the scenes, such as cooking, cleaning, and sexual availability. This probably isn’t a shock to any of the readers. Officially, the organization supported women’s struggles; but only from within a strangely articulated frame. Their 10th point in the Program and Platform began, “We want equality for women. Machismo must be revolutionary … not oppressive.” It was well intentioned, but it was also clear from the supporting language (e.g., pronoun usage) that the men really didn’t know what they were talking about. Women began meeting in a women’s caucus, reading internationalist feminist texts, and pushed back against the machismo, which in their analysis was a particular form of sexism rooted in the intersections of racism, sexism, capitalism, and anchored in coloniality. Of course, men in the group pushed back as well, wielding institutional power to punish them, verbally berating and deriding them, and physically assaulting them. Eventually, they won a major victory that resulted in significant structural changes in the organization, including the virtual elimination of the chairperson position (so they could more effectively govern by committee), the inclusion of women in leadership positions, and inclusion of women in all aspects of the organization (including the Defense Ministry). There was always resistance to those advancements, of course, but I think they still did more and accomplished it faster than many similar organizations at that time. They also produced a marvelous “Position Paper on Women” that laid out their position on women in the struggle, and even extended their intersectional critique of the social construction of gender into sexuality—forming a gay and lesbian caucus and fighting for trans* rights alongside Stonewall combatant and STAR founder Sylvia Rivera.

Blain: What is the biggest misconception that you think many people have about the Young Lords? How does your book clarify this misconception?

Wanzer-Serrano: I think the biggest misconception people have about the Young Lords in New York is that they were a gang. I think this misconception is rooted in the gang roots of the original Chicago chapter. You see, in Chicago, José “Cha Cha” Jiménez had been in the Young Lords gang since 1959, when it emerged in response to manifold forms of abuse Puerto Ricans faced from white neighborhood gangs. Spending time in and out of jail, Jiménez again found himself incarcerated in 1968. While in the Cook County Jail on drug charges, Jiménez befriended a Black Muslim librarian and began reading widely. Central to his emergent consciousness were the works of Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and the American Catholic Thomas Merton, from whose Seven Storey Mountain Jiménez drew a vocabulary for conversion. “When Cha Cha got out of jail,” recounted Iris Morales, “he returned to his neighborhood and organized the Young Lords to protest the city’s urban renewal plans that would have uprooted the Puerto Rican/ Latino community.” In the fall of 1968, Jiménez transformed the gang into the Young Lords Organization, which operated in coalition with the Black Panthers and Young Patriots under the banner, as I mentioned earlier, of the original Rainbow Coalition. As I make clear in the book, the New York Young Lords had a different trajectory. While there were individual members who had been parts of gangs, the organization itself didn’t have any kind of gang roots. Rather—and this is complicated given the different origin stories that have been told—the New York chapter formed through a merger of a few different groups that were focused on community activism, education, and art.

Blain: How would you summarize the historical legacy and/or significance of the Young Lords? How would you summarize its relevance for contemporary Latino/a and Black politics?

Wanzer-Serrano: In one sentence, I’d say that the Young Lords were the most significant post-McCarthy era radical Puerto Rican organization in and of the diaspora, who inspired a generation of young people to assert their humanity in the face of an oppressive, violent, racist-sexist-capitalist-colonialist system. Although other Puerto Rican groups, which had formed on the island, had a presence in New York City at the time, their specific analyses didn’t speak to the unique conditions of Puerto Ricans and other oppressed peoples in New York City in the same way that the Young Lords did. The emergence of the Young Lords gave voice to a group of peoples and their interests that had escaped the attention of other radical groups and social service organizations. Furthermore, the Young Lords helped spark the imagination—politically, artistically, and more—of their generation. They showed people that they didn’t have to meet the societal expectations that they be docile, disenfranchised outsiders.

I think their relevance for us today is at least twofold. First, the Young Lords showed us that it’s important to recover a history of activism to empower yourself. They did this by drawing from the few English language resources available at the time to craft their own popular history of revolution in Puerto Rico and internationally. I think that lesson and their methods for doing so remain valuable for us today. As a critical-interpretive history of the Young Lords, my book is an attempt to engage in practices of historia to craft a story of change over time that can energize a new generation of activists today. This is a story that isn’t taught in our school systems and is barely (if at all) glossed even in some of the best universities. At the same time, I recognize that my history (any history, for that matter) is incomplete; so I hope that the book can inspire others to offer their own angles on explaining the Young Lords, conduct research on the other branches, etc. Furthermore, specific elements of that history are vitally important. For example, I think that the Young Lords’ focus on “community control” can be incredibly useful in Black and Latin@ communities today. The old maxim “all politics is local” continues to hold truth. Even in an era marked by the rise of neoliberal globalization and transnational information flows that make the world a smaller place for some, local grassroots politics remains relevant and vitally important. The Young Lords and others in common cause laid an intellectual and practical infrastructure for instigating change by speaking with diverse and allied voices to demand justice in their communities. Rhetorics of community control are malleable enough to have force within various systemic constraints, in part, because they neither have inherent conflict with neoliberal rhetorics of “personal responsibility” nor do they require calling for or operating within a logic of “revolution.” Instead, at their heart they retain a decolonial commitment to local knowledge and invite attentiveness to the plurality of interests and perspectives that animate community togetherness—commitments that must be retained, cultivated, and strengthened in order to guard against neoliberal co-optation.

Second, I think that the Young Lords’ decoloniality offers another point of relevance for us today. On the one hand, they fill out our understanding of what decoloniality can look like on the ground, which helps to advance us beyond the more abstract, theoretical formulations of decoloniality that occupy the majority of existent literature. That knowledge has practical application in activist politics, but also it has scholarly application insofar as it gives us things on which to focus our critical attention in order to better understand how other groups and individuals engage in projects that challenge modernity/coloniality. On the other hand, their model of decoloniality contains lessons for scholarly critical praxis. Building off the excellent work of scholars like Nelson Maldonado-Torres, Chela Sandoval, and Kelly Oliver, I’ve tried to advance an ethics of decolonial love that points to a particular set of scholarly critical practices that are crucial if we are to challenge the hegemony of (western) Man in the manner that folks like Sylvia Wynter, Alexander Weheliye, and Frantz Fanon demand. As I write in the conclusion, we who are colonized or function in some way otherwise cannot be the only ones leading the charge to delink from modernity/coloniality. An ethic of decolonial love requires those who benefit most from the epistemic violence of the West to renounce their privilege, give the gift of hearing, and engage in forms of praxis that can negotiate more productively the borderlands between inside and outside, in thought and in being. It is crucial that all scholars and activists begin to take decolonial options seriously if we wish to do more than perpetuate “a permanent state of exception” that dehumanizes subalterns and maintains the hubris of a totalizing and exclusionary episteme.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.