You Can’t Eat Freedom: A New Book on Rural South Activism after the Civil Rights Movement

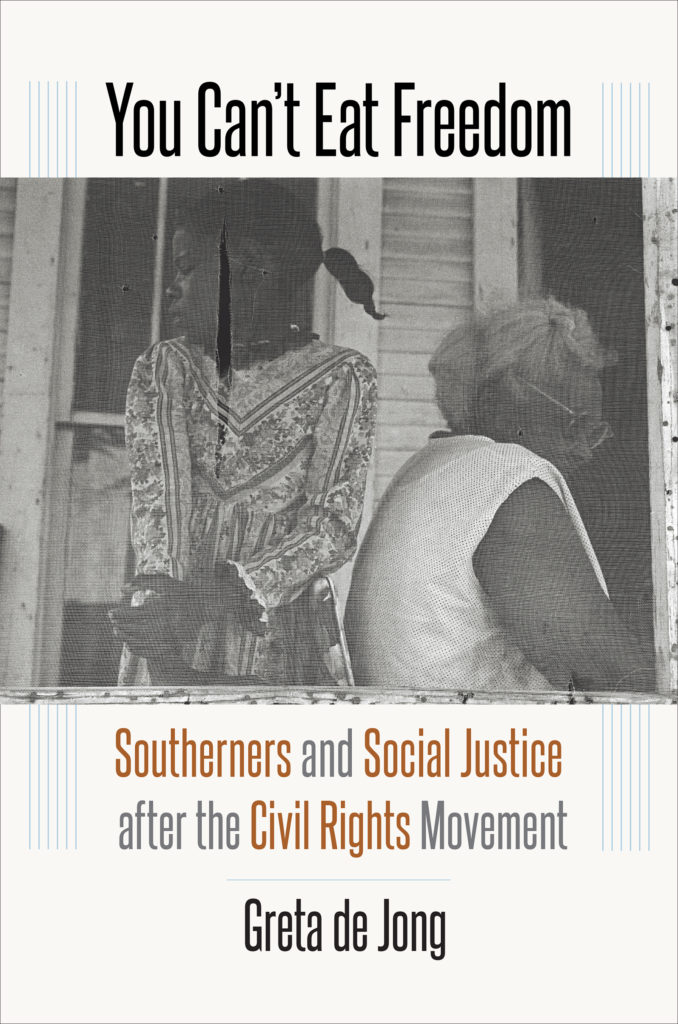

This post is part of a recurring blog series I am editing, which announces the release of selected new works in African American and African Diaspora History. Today is the official release date for You Can’t Eat Freedom: Southerners and Social Justice after the Civil Rights Movement, published by The University of North Carolina Press.

***

The author of You Can’t Eat Freedom is Greta de Jong. Professor de Jong is an associate professor of history at the University of Nevada, Reno. She completed her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in New Zealand and worked as an editor for eighteen months before coming to the United States to complete a Ph.D. degree at the Pennsylvania State University. She held a fellowship at the Carter G. Woodson Institute for Afro-American and African Studies at the University of Virginia and teaching positions at George Mason University and the University of Wisconsin-Parkside before taking a position at the University of Nevada, Reno in 2002.

The author of You Can’t Eat Freedom is Greta de Jong. Professor de Jong is an associate professor of history at the University of Nevada, Reno. She completed her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in New Zealand and worked as an editor for eighteen months before coming to the United States to complete a Ph.D. degree at the Pennsylvania State University. She held a fellowship at the Carter G. Woodson Institute for Afro-American and African Studies at the University of Virginia and teaching positions at George Mason University and the University of Wisconsin-Parkside before taking a position at the University of Nevada, Reno in 2002.

de Jong’s research focuses on the connections between race and class and the ways that African Americans have fought for economic as well as political rights from the end of Reconstruction through the twenty-first century. She has written two other books, A Different Day: African American Struggles for Justice in Rural Louisiana, 1900–1970 (University of North Carolina Press, 2002) and Invisible Enemy: The African American Freedom Struggle after 1965 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010). Her current project is a study of the tensions among family, community, and justice that emerged during struggles over school desegregation in the mid-twentieth century.

Two revolutions roiled the rural South after the mid-1960s: the political revolution wrought by the passage of civil rights legislation, and the ongoing economic revolution brought about by increasing agricultural mechanization. Political empowerment for black southerners coincided with the transformation of southern agriculture and the displacement of thousands of former sharecroppers from the land. Focusing on the plantation regions of Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi, Greta de Jong analyzes how social justice activists responded to mass unemployment by lobbying political leaders, initiating antipoverty projects, and forming cooperative enterprises that fostered economic and political autonomy, efforts that encountered strong opposition from free market proponents who opposed government action to solve the crisis.

Making clear the relationship between the civil rights movement and the War on Poverty, this history of rural organizing shows how responses to labor displacement in the South shaped the experiences of other Americans who were affected by mass layoffs in the late twentieth century, shedding light on a debate that continues to reverberate today.

“With an impressive breadth of research, You Can’t Eat Freedom takes us inside communities fighting for civil rights after 1965, looking beyond the much studied earlier period to show us how these ongoing racial struggles were contested on the ground. This book does not shy away from highlighting the prevalence of black poverty after 1965, avoiding the temptation to find silver linings in what is quite a sobering–even bleak–story. This is a nice corrective to the triumphal nature of some civil rights historiography.”

—Timothy J. Minchin, coauthor of After the Dream: Black and White Southerners since 1965

***

Ibram Kendi: Did you face any challenges conceiving of, researching, writing, revising, publishing, or promoting this book? If so, please share those challenges and how you overcame them?

Greta de Jong: I did have trouble conceiving of the project in a way that made it manageable. I had studied the freedom struggle in Louisiana for my dissertation research and first book. Originally, my plan for You Can’t Eat Freedom was to examine how black southerners continued to fight for racial justice after the 1960s and the obstacles that white supremacists continued to place in their way. I expanded my geographical scope to include the plantation regions of Alabama and Mississippi as well as Louisiana, which meant it took longer to research than if I had chosen to focus on a single state. And there was so much to cover in the struggles over economic justice, education, social welfare policy, political power, and other concerns that continued in the late twentieth century. I also took a detour to write Invisible Enemy for Wiley-Blackwell, which meant that some chapters of this book were drafted years apart and at different stages of my thinking on these topics.

Working on Invisible Enemy in between my first book and this one delayed completion of this project for several years, but it also helped me to develop a better sense of what I wanted to do and the contributions I was seeking to make to the historiography. In the end, it all came together after I narrowed the focus down to the problem of labor displacement and the ways that plantation owners, social justice activists, and federal policy makers responded to that. Once I did that, it was much easier to revise the earlier chapters and write new ones that would frame everything into a coherent whole.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.