“Yet Lives and Fights”: Riots, Resistance, and Reconstruction

How civil war in the South began again—indeed had never ceased; and how black Prometheus bound to the Rock of Ages by hate, hurt and humiliation, has his vitals eaten out as they grow, yet lives and fights.~W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America

Reconstruction, in most states, went forward by blood, not by decree.

In July 1866, Republicans gathered at the Mechanics Institute in New Orleans to discuss drafting a new state constitution. Despite stubborn Democratic and pro-Confederate resistance, Republicans—a coalition of abolitionists, Northern whites, Unionist southerners, members of Louisiana’s large formerly free community of color, and those recently freed by the assassinated Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation—believed they could successfully draft a state constitution that offered suffrage to freedmen and citizenship to freed men, women, and children in the aftermath of the Civil War. Some of these Republicans were idealists; some were naive. Most had faith in the strength of their coalition.

When the sun dawned on July 30, 1866, over the sixth ward of New Orleans, residents of the city gathered to watch the events. Politics remained the formal terrain of white and, to a limited extent still, black men, especially black veterans. However, men, women, and young people of all races made their way to the sites of meetings. Black residents in particular listened at windows and gathered in the street outside meeting places to discuss among themselves what citizenship and suffrage meant for them in a post-emancipation society. Political meetings would also have been opportunities for petty commerce as coffee and praline women and watermelon men sold their wares to would-be politicos arriving and departing the scene. Black residents would also have been going about their business on that day, hurrying from one place to another, oblivious to what was about to happen.

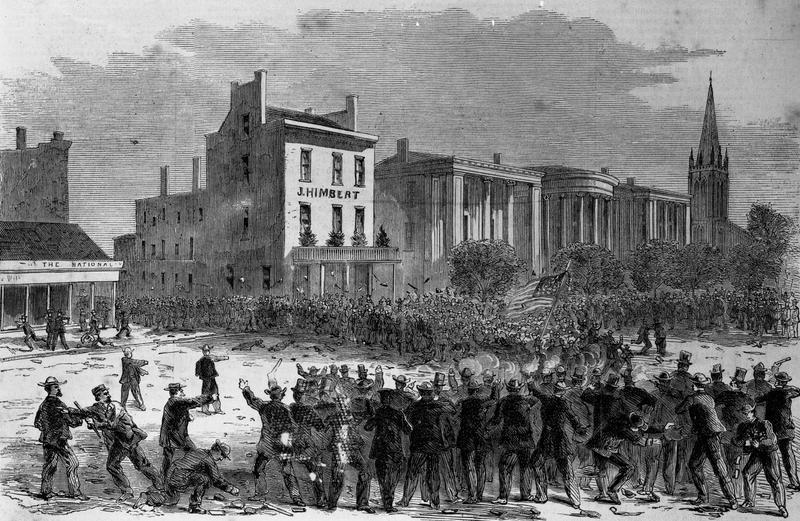

Tensions rose as marchers moved through the city. Many were harassed on their way, including by police gathered for the occasion. One man was arrested. Convention attendees finally arrived at the meeting place—only for police to turn on them and begin shooting. Details around the riot differ. W. E. B. Du Bois describes the beginning of the massacre as initiated by “a signal shot…and the mob deployed across the head of Dryades Street, moved upon the State House, and shot down the people who were in the hall.”

Black veterans and residents returned fire, scrambled into the building for protection, and mob violence scattered in all directions as spectators fell to gun shots, assaults, and marauding white rioters. General Baird mobilized federal troops to end the fighting, but arrived too late to stop the worst of the battle. About forty to fifty people were killed. Three white victims stood out as Republican members of the convention or vocal sympathizers: A. P. Dostie, a local dentist; Republican member John Henderson; and Rev. Jothan Horton. The vast majority—Du Bois claims the rest of the dead—were black people.

When General Sheridan gathered reports on the fighting later, he described it as a massacre:

The more information I obtain of the affair of the 30th in this city the more revolting it becomes. It was no riot; it was an absolute massacre by the police which was not excelled in murderous cruelty by that of Fort Pillow. It was a murder which the mayor and police of this city perpetrated without the shadow of a necessity: furthermore, I believe it was premeditated, and every indication points to this. 1

The Mechanics’ Institute (or Mechanics Hall) Massacre, considered one of the most violent race riots of the Reconstruction era, helped to usher in Congressional Reconstruction, providing Congress with an excuse to propose (and for states to ratify) the Fourteenth (1868) and Fifteenth Amendments (1870). It followed conversations and attempts at the federal and state level to extend suffrage to black men, including deliberate organizing by formerly free blacks, black veterans, and a black community determined to fight for an end to even the shadow of bondage.

It is discussed by historians as a race riot and as a street brawl, but not always in the terms offered by Sheridan when he reported on it to his superiors. By comparing it to Fort Pillow, Sheridan placed the Mechanics Institute Massacre both in the tradition of war—skirmishes and battles between states—and in the tradition of state violence against black people who dared to bear arms, exercise their right to participate in the political process, take up space in the cities and towns they live in, and fight for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

The archive for the Reconstruction era is filled with moments like these—black men, women, and children determined to live out the promises of emancipation and move forward, progress, make change, and find themselves facing unbelievable levels of state violence and repression. There were bloody, dark, and terrible moments where lives were lost and it seemed like the promise of freedom would not be fulfilled. And there is no solace in or for these moments.

Black Prometheus “yet lives and fight” again and again, but it doesn’t feel good and it isn’t easy. The people killed in New Orleans that summer day did not return to their families, and to describe those who lived the tale as having survived does not capture the pain, fury, and grief of the experience or the betrayal of the promise of emancipation. Nor can pragmatism be comforting or comfortable. Presumably black veterans attending the meeting bore arms, just in case. This likely helped some in the moment against the abject state violence enacted against them, but their arms did not then and do not now help us mourn.

What Reconstruction does teach us is that the bloodiest struggles and the most terrible betrayals have always occurred in the wake of black success, of gains in a freedom struggle that has been in motion since Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619 (and in New Orleans in 1719).

Whatever might be at stake since the results began filtering in on Tuesday night, it is clear that the country remains in the throes of that battle, and that is, indeed, a civil war and epic struggle to define what freedom means and who it will include. It also continues to be a bloody struggle. While we have yet to see how bloody this 21st-century battle will get, a terrible truth must be faced—it will get worse before it gets better. And the worse it gets, more than likely, the closer we are to a port in the storm and the harder we need to fight. This is what Reconstruction teaches us.

- Telegram, P. H. Sheridan to U. S. Grant, August 2, 1866, in House, New Orleans Riots, 11. ↩

I do not have a comment as much as a question. If you have time I would appreciate a synopsis of General Grant’s response to General Sheridan’s Telegram. Thank you very much in advance, Lee.

Hi Terry,

I’m posting General Grant’s response to the African Diaspora, Ph.D. Tumblr along with a link to the House documents which happen to have been digitized by Google Books.

Find it here: http://africandiasporaphd.tumblr.com/post/153143286664/see-more-here

Grant’s response is rather formulaic; then-President Johnson’s response is more interesting as he seems to sympathize with the Mayor and against the “rioters” (Republicans, free blacks, etc.).

Thanks,

Jessica