“Why Aren’t Black People More Optimistic?”

In a 1968 interview, television personality Dick Cavett asked James Baldwin, renowned author-activist, what many white Americans at that time had been wondering: why aren’t Black people more optimistic? Even as they faced systematic oppression, racism, and other problems, African Americans were making significant progress. That is, as Cavett continued, Blacks were mayors, they were in sports and politics, and “they’re afforded the ultimate accolade of being in TV commercials now. Is it at once getting much better and hopeless” for Blacks in America?

This fifty-year-old question—one notably posed in the same year as Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination—was relevant then and still resonates today. At the crux of it is a fundamental dualism and tension that far too often punctuates Black life with simultaneous progress and hopelessness, advancement and seemingly incorrigible despair. And even a half-decade later, this inquiry, almost like a leading question with a built-in answer, reverberates resoundingly.

Black people have and continue to progress substantially. We have witnessed Blacks serve as not only mayors and in politics, but we have also experienced the first Black US President, Barack Obama, serve two terms in the highest post in America. There are Black billionaires such as Michael Jordan, sports legend and astute entrepreneur, as well as the media mogul and businesswoman-extraordinaire Oprah Winfrey. Add to that the catalog of countless Black athletes who play and dominate in a range of sports. And even more recently, we witnessed a historic moment when directors Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther and Ava DuVernay’s A Wrinkle in Time broke cinematic terrain for a variety of reasons—and, impressively, for earning the top-two box office spots in a historic achievement. To be sure, this is a particular echelon of greatness that most people, regardless of race, do not achieve. So while it is not the standard for the mass majority, it does nonetheless mark what is possible when Black people are endowed with and afforded rights and the freedom to do, to be, to achieve, and to exist.

And perhaps that precisely is why films like Black Panther, with a place uncontaminated by colonization and Blackness unsullied by the West, or Wrinkle—wherein one could travel across time and, in the process, save one’s self and the world from the very entity, the enemy, seeking destruction—are appealing. For a moment, if even temporarily, Black people could absorb the aesthetic opulence and possibilities. They could consume with pride the solace, the eloquence, and the escape: to contemplate life in Wakanda or to imagine a world where we could travel across place and time. In the breathtaking visuals, the arresting imagery, the cultural dynamics, and sentiments, Coogler’s and DuVernay’s films have sustained us, filled us with joy, and afforded us the capacity to relish in our humanity reflected on the screen. Yet, it was short-lived. We were transported back to the stark reality and reminded, as if it were a backlash, of the exponential assaults on Black life, of the far-too-often state-sanctioned violence against our bodies and our very humanity, in the recent cumulative attacks on Black people.

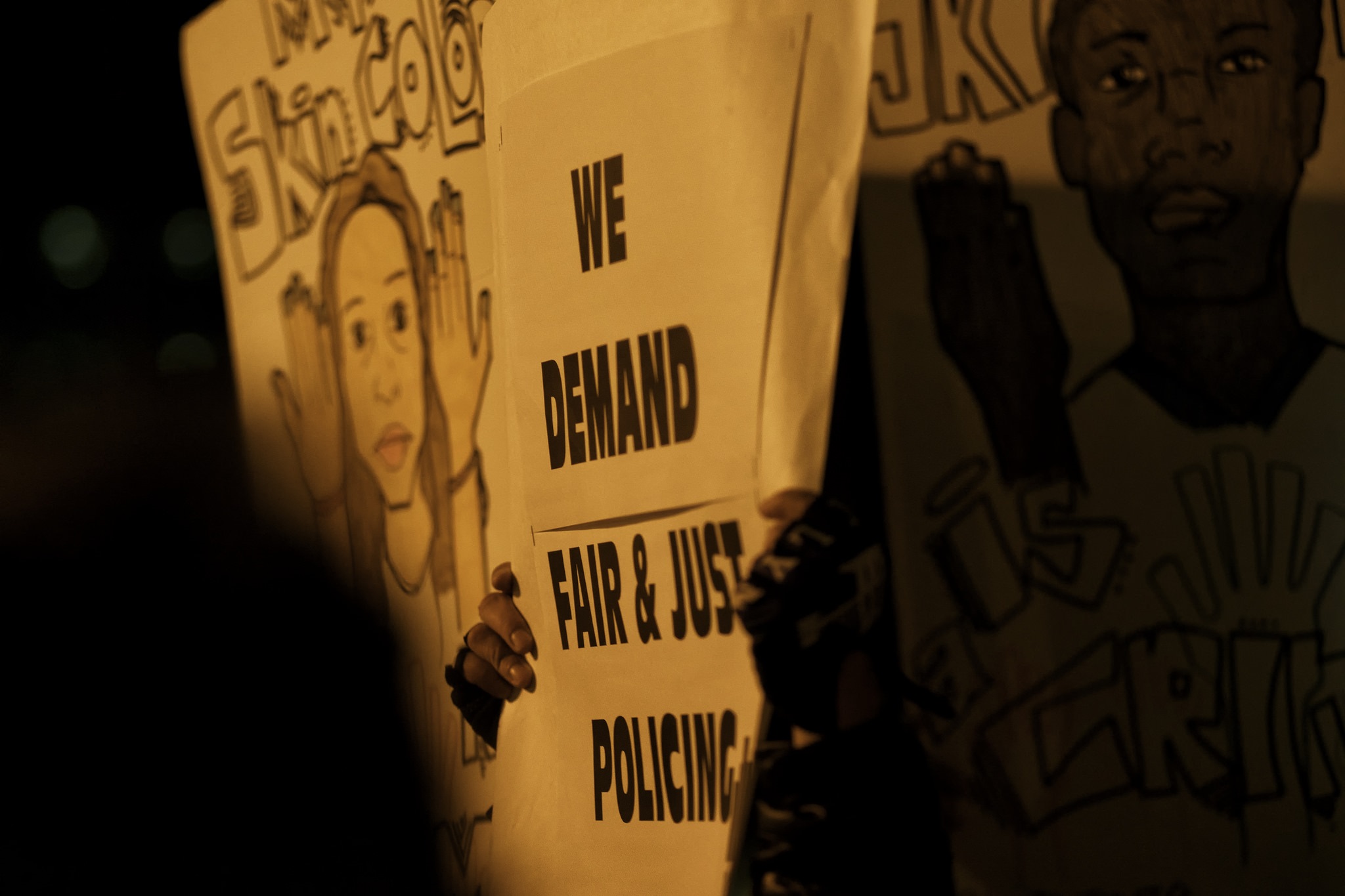

How does one process or make sense of the atrocities inflicted on human beings, flesh and blood, like 39-year-old Anthony House or 17-year-old Draylen Mason, both of whom were targeted and murdered by the Austin bomber with explosive-filled packages on March 2 and 12, respectively? What words or rhetoric begin to convey what happened to 22-year-old Stephon Clark, whom the Sacramento police shot at twenty times, with eight bullets lodged in his body, in his very own (grandmother’s) backyard on March 18? He was unarmed with merely a cell phone in his hand. Six days prior, police killed 34-year-old Decynthia Clements after she took two steps out of her vehicle in Elgin, Illinois. Instead of de-escalating the situation and using non-fatal interventions, the police shot Clements in the head accounting for—like that of House, Mason, and Clark—her unnecessary and untimely death.

Days later, in Louisiana, state authorities announced that they would bring no charges against the two Baton Rouge police officers involved in the killing of Alton Sterling, shot and killed in July 2016 by Blane Salamoni who used deadly, excessive force. It comes as absolutely no surprise to some, though deplorable, that the state did not charge these officers. For in the words of Quinyetta McMillon, the mother of Sterling’s son, “We all knew what it was just like y’all knew what it was going to be.” In this year alone, as of April 5, 2018, police have used deadly force, shooting and killing, 294 people, according to the 2018 Washington Post’s national police shootings database. Regardless of race officers customarily are not indicted, charged, arrested, or even fired—in some cases—when they use excessive lethal force on Black people, unarmed or armed, women or men, young or old.

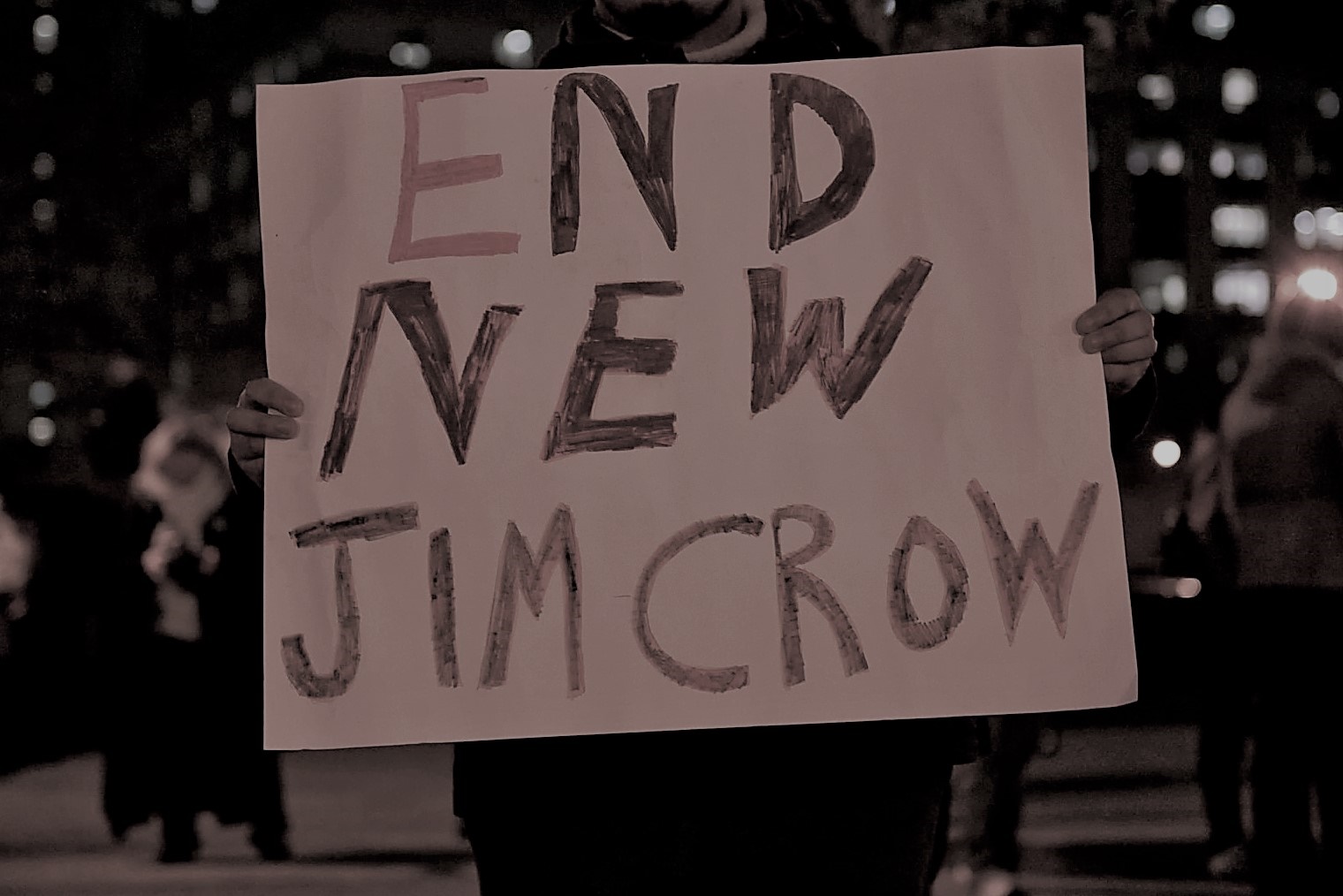

A Somali-American police officer, Mohamed Noor, who fatally shot a white Australian woman in Minneapolis, was charged with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. Some have called into question what appears to be double standards concerning race in police-involved killings. “We don’t feel that officer Noor was treated the same way as other officers were treated that were in [a] similar situation as him,” noted Waheid Siraach, the Somali-American Police Association spokesperson. “The only difference [. . .] is that the deceased person in this case happens to be a white woman and the officer involved in this case happens to be a black officer” and, he continues, “he’s also a Muslim and he’s a Somali.” Minnesota is also where an officer shot and killed Philando Castille while he was driving with loved ones as people witnessed his murder in real time on social media. The officer who killed Castille, who used a similar “rationale” as that of Noor, was not only acquitted, found not guilty, of all charges, but he will also reportedly receive $48,500 in a buyout as he leaves the department where he worked at the time of the fatal shooting.

Failure to charge police officers for the murder of Blacks is not new, nor is the strategic assault on Black folks a contemporary phenomenon. Exactly forty years ago, in 1978, June Jordan—poet, writer, and activist—penned her indictment and poetic diatribe, inspired in part because of the controversial officer-involved killings of Black citizens in New York City. In “Poem about Police Violence,” Jordan writes, “I lose consciousness of ugly bestial rabid and repetitive affront [. . .] when they tell me/18 cops in order to subdue one man.” And she closes with a controversial refrain: “tell me something/what you think would happen if/everytime they kill a black boy/then we kill a cop/ everytime they kill a black man/then we kill a cop/you think the accident rate would lower subsequently?”

To be clear, I am in no way referencing Jordan to suggest retaliation or the killings of police. Bloodshed does not bequeath justice. What Jordan’s poem does is imbue Black bodies with humanity and forces us to think about Black people’s right to life and the fallacy of authority when police officers kill Black folks in seeming pedestrian-like fashion with impunity. Jordan’s poem importantly illuminates and begs us to contemplate: what if the value and premium we ascribe to (white) police and, by extension, place on white lives, we equally ascribe to Black people’s lives? Would that mitigate or lessen the number of police-involved shootings of Black folks? And similarly provocative if the very thought of the death of a cop offends, enrages, or causes you to cringe or experience aggrievement, where is that same level of empathy or moral outrage in the same scenarios when police kill Black people, cutting short their lives?

Why aren’t Black people more optimistic? Is it at once getting much better and hopeless? To shed light on these, we only need to return to James Baldwin who eloquently and cogently put it best regarding race, optimism, and the future of America: “I am not a pessimist because I am alive. To be a pessimist, it means that you have agreed that human life is an academic matter. So I am forced to be an optimist. I’m forced to believe that we can survive whatever we must survive.” The future of Black people, Baldwin continues, is “precisely as bright or as dark as the future of the country. It is entirely up to the American people and our representatives [. . .] whether or not they will deal with and embrace the stranger they have maligned for so long.”

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.