What to the Black Academic is the 4th of July?

July 4 is not normally a day that we associate with black history. The “we” here refers both to the average citizen and the average statesman, for while one seldom sees black sponsored July 4 productions commemorating black history, it is perhaps more rare to see state-sponsored productions focusing on black contributions to American independence.

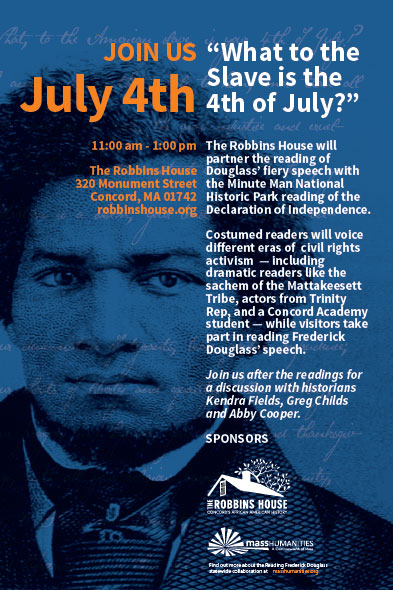

So it was with some measure of delight that I received word from a colleague and good friend at Tufts University that the Robbins House in Concord, Massachusetts– an organization dedicated to preserving the home “formerly inhabited by the first generation of descendants of formerly enslaved African American Revolutionary War veteran Caesar Robbins”- wanted us to come to a re-enactment of Frederick Douglass’s 1852 speech to the Ladies Anti-Slavery Society of Rochester, NY “What to a slave is the 4th of July ?”1 We had attended the same event together the previous year and now the organizers of the Robbins House wanted us to return and serve as historical experts who could answer questions from the audience about Douglass and about slavery and freedom in the nineteenth century more broadly. Having just participated in the AAIHS roundtable on Neil Roberts’s Freedom as Marronage, I felt more ready than usual to talk to a public, non academic audience about the ways that black men and women in nineteenth century America lived through, thought about, and theorized from the standpoint of being a fugitive.

The speech was reenacted impressively and with passion by members of the Minute Man National Historical Park, along with help from audience volunteers who also got on stage and recited some paragraphs from Douglass’s speech. We came forward after it ended and took our place on the podium to begin answering questions.

Everything started smoothly enough. We initially got some questions from audience members who just wanted to know more about Douglass and anti-slavery activism: “what did Douglass do after the speech in terms of his career?” for example, and “When did Douglas die and how did people feel about that?” As the question and answer continued, however, we started to get questions that were quite pointed and had nothing to do with Douglas or slavery. First there was a question about hope and despair, or rather how we maintain hope in such disparaging times considering the possibilities for who our next president will be. Then there was a question about why can’t we say “all lives matter” today. Problematic questions, of course, but my colleague and I regarded these questions as being asked in sincerity, as being asked by people who genuinely wanted to know if we had answers they hadn’t heard before. And so we responded with educational kindness: by explaining to the one questioner the various ways that holding on to black joy and hope has always required looking beyond and outside of formal electoral politics, and by telling the second questioner that we can’t say “all lives matter” because that very same notion has already been historically practiced and encoded in American politics in sentiments like “all men are created equal”– statements that only signified white people and thus have more than a residue of inequality structured into them.

Everything started smoothly enough. We initially got some questions from audience members who just wanted to know more about Douglass and anti-slavery activism: “what did Douglass do after the speech in terms of his career?” for example, and “When did Douglas die and how did people feel about that?” As the question and answer continued, however, we started to get questions that were quite pointed and had nothing to do with Douglas or slavery. First there was a question about hope and despair, or rather how we maintain hope in such disparaging times considering the possibilities for who our next president will be. Then there was a question about why can’t we say “all lives matter” today. Problematic questions, of course, but my colleague and I regarded these questions as being asked in sincerity, as being asked by people who genuinely wanted to know if we had answers they hadn’t heard before. And so we responded with educational kindness: by explaining to the one questioner the various ways that holding on to black joy and hope has always required looking beyond and outside of formal electoral politics, and by telling the second questioner that we can’t say “all lives matter” because that very same notion has already been historically practiced and encoded in American politics in sentiments like “all men are created equal”– statements that only signified white people and thus have more than a residue of inequality structured into them.

So we made it through those questions and finished up the session without much of a hiccup. The moderator gave some closing remarks, which were followed by a light round of applause, and everyone began to gather their things to go. So far, so good still. Yet as we were grabbing our things and preparing to leave that’s when the questioner who I thought we had escaped began to make his way to the podium.

More than likely you know the kind of questioner I am talking about. They sit through your entire presentation or session but never speak during the question and answer segment. In fact they do not even raise their hand to attempt to ask you anything in that moment and so they are not foremost in your mind as you are concluding your panel and thinking about what went well and what went wrong. They do not even come up to the podium or the table after the panel is done to talk with the panelists or with other audience members, but rather wait in the wings until you are alone or without an audience or about to transition from your mental work-space to your mental relaxation-space before approaching you. And so because they are not foremost in your thoughts, and because you are thinking about your presentation as being done you are blindsided by them and by what can only be received as a hostile line of questioning.

“I hear a lot of you academics talk about police killing black kids,” he started, “but where’s the intellectual or academic response to what’s happened in Chicago over the weekend? What do you do about that?”

So we were far away from Frederick Douglass, far away from anything historical and squarely in the moment of the now. It was too much to tackle right then and there and not what I had been brought to discuss. My first instinct was to be both sarcastic and to try to be serious at the same time by saying that if we could all just beat the hell out of a slave breaker like Douglas did maybe that would solve the problem. But I refrained and held myself in check and simply said “yeah, no, what do you think about it?”

I don’t recall everything he said, but it was something along the lines of we need community improvement, need to create good schools, and give everybody a little piece of land that they can buy so that they feel… You know the rest. I had neither the kindness, nor patience left to inform him that he sounded like almost every gradual abolitionist who was concerned about how to free black people from slavery and get them “ready “for citizenship under white tutelage. So I let him go on for a few minutes, respectfully said thank you, and took my leave.

Now we know what happened the next two days after this year’s July 4. On Tuesday, July 5, Alton Sterling was killed by police in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Then on Wednesday, July 6, Philando Castile was shot and killed by police in Falcon Heights, Minnesota. As I received news of both of these events I thought back to the question we had been asked about killings in Chicago and how to stop “black-on-black crime.” I thought with relish at first “wow, I’d like to be able to talk to that gentleman again today and ask him if he still feels his question is warranted after what can only be called police executions of civilian black men.”

Almost immediately after this, however, another thought came to mind, something more urgent and more demoralizing. Why was I concerned with proving wrong an older white male from Concord whom I didn’t know at a moment like this? Why did my thoughts turn at all towards this individual who only wanted black folks to care for one another so that we could explain ourselves to him and eventually look “better” and more like “normal” citizens to white America?

At the same time I had to acknowledge that he was only able to ask that question because of the public perception and representation of Douglass as a “model negro” for whites. I had to recognize that even as liberal whites have listened to the speeches of Douglass or Obama and occasionally heard themselves indicted for failing to be truly progressive, at the end of these fiery orations they have historically still been palliated by the fact that the “angry black man” is still thinking about and talking to them. And after allowing myself to think through this, my question became not why this white male expected an answer from black intellectuals about solving black crime, but rather why is it that in moments of crisis and tragedy a great many of us black intellectuals can only think about the white gaze or about the image of the black person in the white imagination? What would it look like if we rigorously cultivated and practiced thinking with one another and about one another without concern for our public representation in front of white people or without concern for speaking truth to white power?

Of course there is a serious need for black voices in public forums, and I am certainly not making a call for less black public voices or asking for peace without protest or resistance. I am only calling for more attention and asking for more concerted consideration of how easily our mental space becomes occupied by the image of the white audience in the most harrowing moments of Black history, how our efforts to receive news about and heal from devastating racial violence often continues to compete from the outset with caring about whiteness in some form or another. In this sense, then, I share Kevin Quashie‘s concern that while we need resistance, and while resistance has been meaningful beyond measure to Black strivings, we have to think of stronger ways to cultivate the interiority of blackness, a deep and rich well of thought that cannot be subsumed to the white gaze and white concerns for how black people look to, and resist against, a white public.2

I’m very moved by the self-reflexivity and vulnerability that you’ve followed and made public here. The call to cultivate “the interiority of blackness” speaks to the need to rethink blackness, to frame a narrative that is not exclusively centered on resistance to white racism. Resistance is hugely important, but it has us constantly reacting against anti-blackness.

I’m just now reading an instructive book, “Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology,” that points to the limits of the common progress-against-racism narrative and outlines some parameters for different starting points. It’s provocative and carefully written. I’m encouraged to see blackness on the move, something to be shaped, cultivated, and interrogated. A project rather than a place.