What is Happening in Waller County?: Sandra Bland and the Sister Comrades Who #sayhername

On Friday, July 10, 2015, just outside of the campus of Prairie View A&M University (PVAMU) in Waller County, a Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) officer named Brian Encinia pulled over 28-year-old Sandra Bland, and subsequently arrested her. Three days later, and about seven miles from where law enforcement handcuffed, arrested, and detained her, Bland was dead inside of the Waller County Jail, located in the small town of Hempstead.

The aim of this post is not to narrate the details of Bland’s case so far. Many domestic newspapers, magazines, and radio programs have done so. You can find reports in the Atlanta Daily World, Atlantic, Chicago Tribune, Democracy Now (and here), The Washington Post, Houston Chronicle, Voice of Detroit, New York Times (here too), Boston Globe, Truthdig, Huffington Post, New York Amsterdam News, CounterPunch, Workers World, Los Angeles Times, The Intercept, Uprising, San Francisco Bay View, People’s World, and Final Call. International outlets have also spotlighted events in Waller County, such as Russia Today (also here and here), The Independent (also here), Al Jazeera, and International Business Times. These stories have reported on various aspects of Sandra Bland’s case, such as the conflicting and contradictory claims of Waller County officials about what exactly happened to Bland inside the jail, not to mention the problems with Brian Encinia’s arrest report, among other issues.

Rather, the aim of this post is to offer a local look at some of what’s been happening in Waller County since Bland’s death. I live about 20 minutes from PVAMU, and about half an hour from Waller County Jail. I have conducted research in the archives at PVAMU over the last several years for a project on W. E. B. Du Bois and Texas, and I am a former resident of Waller County. I know the campus and the county well.

To invoke the work of Jeanne Theoharis and Komozi Woodard in Groundwork: Local Black Freedom Movements in America (NYU Press, 2005), there’s a local Waller County perspective I’d like to highlight in this post. In the Introduction, Theoharis and Woodard note “the groundbreaking work of local people across the country who challenged the racial caste system in the United States. These local people drove the Black Freedom Movement: they organized it, imagined it, mobilized and cultivated it; they did the daily work that made the struggle possible and endured the drudgery and retaliation, fear and anticipation, joy and comradeship that building a movement entails” (1). The editors further describe “local people” in terms of “a political orientation, a sense of accountability and an ethical commitment to the community. As such, local people were those who struggled with, came out of, and were connected to the grassroots” (3). Theoharis and Woodard’s description of “local people” in previous Black freedom struggles rings true to what I have seen and experienced in Waller County as I’ve followed the Bland case, and as I’ve participated in some of the vigils and actions. The local people with whom I have interacted, some of whom I reference below, are part of the long legacy and long history of civil rights groundwork. And in our contemporary moment of #BlackLivesMatter, these folks are history-making individuals whose collective action seeks to initiate structural and systemic change.

While this post is in no way a definitive account of what is currently happening in Waller County with the Sandra Bland case—the research and writing for this post was current as of the evening of August 11, 2015—I do hope it can serve as one collection of links to stories and other digital spaces where information is available so that readers can continue to stay on top of the fight for justice as we collectively ask #WhatHappnedToSandraBland. In asking about Sandra Bland’s death, we also keep focused attention on evidence in the case, as provided here by activist DeRay McKesson. Finally, posting about Sandra Bland on the AAIHS’s blog is also an open invitation to add helpful resources in the Comments section.

***

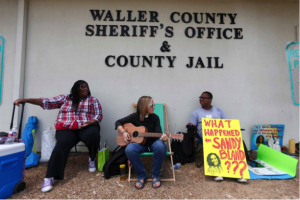

After the story of Bland’s arrest, and death, broke in mid-July, some of the folks first on the ground at Waller County Jail included the Reverend Hannah Bonner, a United Methodist pastor, Rhys Caraway, a local Houstonian who attended PVAMU, and Carie Cauley, a Perkins School of Theology student. The image below, which features Cauley on the left, Bonner, center, and Caraway, right, is from a Houston Chronicle article on Sandra Bland.

On a warm night in July, Hannah, Rhys, and a friend named Nina drove to the Waller County Jail to hold vigil and pray for justice. A candle they lit that evening in Sandra’s honor was the same votive used in remembrance of Charleston a few weeks prior. Adding further religious symbolism to the vigil, and undergirding the righteous nature of the struggle for justice, Reverend Bonner recently built an Ebenezer at the back of Waller County Jail, to which allies have also contributed. Since July, Caraway’s Twitter feed has provided up-to-the minute accounts and has chronicled the ups and downs of holding vigil outside of Waller County Jail. Bonner’s tweets and Instagram updates document a visual, verbal, and digital narrative that tells a story about what’s been happening in Waller County. Her local groundwork has also revealed important facts about Bland’s case, including the curious absence of surveillance cameras at the back of Waller County Jail. Bonner’s on-line writing and blogging, especially about Waller County, brim with insightful observations and critical perspectives. Black Houstonian Ashton Woods, another key figure in the vigils and actions on behalf of Sandra Bland, who also represents GLBTQ interests, has posted about events in Waller County. Among others, the perspectives offered by Caraway, Bonner, and Woods are definitive must reads for anyone who wants to understand the nuances of local civil rights and human rights groundwork happening in Hempstead in relation to the case of Sandra Bland.

Several weeks into holding vigil in Waller County, divinity student Carie Cauley, who drives many miles roundtrip each day to Hempstead to #sayhername, commented that her actions on behalf of Sandra Bland include “praying, and asking the question and joining in unity to ask the question what happened to Sandra Bland . . . we’re standing in the gap.” Karisha Shaw, another Black woman who is traveling to Waller County Jail to #sayhername, also prayed, and commented that her presence signaled “standing up for justice for the life of Sandra Bland, and all the other black lives that have been lost this year alone due to police brutality.” Shaw spoke about the power of local, civil rights groundwork: “With every movement that’s ever had any great momentum, it started with people sitting, just to learn what they were actually dealing with. As long as there’s injustice in the world, I think that people need to be sitting somewhere. And for me, it’s in Waller County.” Fran Watson, yet another Black female participant in the vigils, observed that being present at Waller County Jail to name the system of white supremacy that killed Sandra Bland was necessary because “black people don’t feel safe. So, that’s a problem. That’s a problem.”

Cauley, Shaw, Woods, Bonner, Caraway, and Watson, along with other allies and local activists, organizers, and university students, have braved the scorching Texas heat topping out at over 100 degrees some days, to press Waller Country officials for the truth, and to proclaim solidarity. Pastor Alexis, a Black minister, showed up in Waller County to express support and proclaim the dignity of Sandra Bland’s life and words. Additionally, two white clergy from Chicago, Carol Hill and Rachel Birkhahn-Rommelfanger, traveled to Waller County. Pastor Hill even asked the jail directly, “What happened to Sandra Bland?” And AME minister David Madison showed up for Sandra Bland too.

Erin Hawkins, a Black woman who works for the United Methodist Church as the General Secretary for the General Commission on Religion and Race, came to Waller County to show her support. Her article for the United Methodist Reporter “Enough is Enough” not only described her travels to Texas, it presented the weariness of facing daily the reality of police brutality and state-sanctioned violence. “For the last few months, I’ve been caught in what seems like a perpetual struggle, trying to decide whether or not to write a statement after each incidence of violence toward black people at the hands of law enforcement or racist hatemongers,” she wrote. “It seems that just as I find the words to respond to one act of terror, another one becomes the headline story of the day. I can’t form the words fast enough. Truth be told, I can’t process the emotions fast enough to make a statement that fits within the timeline of the ‘talking heads cycle of commentary.’” At the same time, Hawkins expressed the resolve necessary to name injustice in efforts for freedom and dignity. Invoking the faith tradition that she represents, Hawkins vowed to continue the struggle. She stated: “There simply aren’t enough words, enough statements to do justice to the truth that all people of good will—all people who proclaim to follow Jesus who said, ‘in as much as you did it unto the least of these you did it to me’—must join hands, say ‘enough is enough,’ and take action if we are to break through the physical and spiritual forces of violence and hatred that plague us.” As practical steps to counter the fatigue of fighting for equality, Hawkins sounded a pastoral and prophetic tone, “I believe that prayer is powerful, and I encourage leaders at every level in the Church to continue praying and calling for prayer. I believe that declarations of solidarity and support are an important first step in building relationships with the harmed and hurting. I also believe that if those are the only two things that you are doing in the face of the staggering realities of racism, sexism, and classism—which are being made more and more visible every day, all around the world—then you are a part of the problem.”

The case of Sandra Bland connects fundamentally to the recent deaths of Black men and women at the hands of police officers. It signals yet another tragic example of how state sanctioned white supremacy devalues the lives of Black people, and dehumanizes people of African descent.

In concert with other organized responses to violence against Black bodies, on Sunday, July 9, 2015, a Day of Remembrance and Response took place on the grounds of Waller County Jail. Presenters, very much like the crowd that was assembled, represented a broad cross-section of Black and white, straight and gay, and Christian, Muslim (including members of Houston’s Nation of Islam community), atheist, and humanist. I saw members of the Texas Organizing Project turned out in large numbers, as well as several representatives of the New Black Panther Party. There were even a handful of “#AllLivesMatter” protesters with posters. Rally presenters spoke in support of #BlackLivesMatter; proclaimed the dignity of Black people; acknowledged non-Black allies in justice struggles; announced an economic boycott of Waller County; and said the name of Sandra Bland, encouraging the “kings and queens” present to fight for justice in the same way that Sandra did. The very last speaker at the mic was Sandra Bland herself; rally organizers played a “Sandy Speaks” segment.

After the main speakers concluded, the Houston chapter of the National Black United Front (NBUF) led a spirited yet peaceful march around the jail, circling it three times, which ended with NBUF activists and allies entering (not “storming” as the Houston Chronicle incorrectly stated) the small lobby of Waller County Jail to continue invoking Sandra Bland’s name and calling for answers. After a short time in the lobby, as the peaceful but spirited chanting continued, Waller County Sheriffs forcefully pushed the activists out, slamming and locking the doors. As the push-out ensued, several activists inadvertently got trapped in the lobby. After further protest with marchers demanding the activists be released, Waller County law enforcement officials escorted the activists out of the building’s side exit. Here’s an extended video of the lobby action, which like the writings and tweets of Caraway, Bonner, and Woods, adds very helpful nuanced and detailed coverage of what actually took (and it taking) place in Waller County.

The lobby moment, and the moment when a police officer pulled out a rifle from an unmarked police car, were the tensest of the rally up to that point, which, in stark contrast to some local and national news reports, was expressly peaceful and nonviolent. In response to the lobby fracas, Texas DPS officials suited up in riot gear, a provocative gesture designed to incite reaction, and an entirely unnecessary display of state power. Such a forceful response and display, from my perspective, seemed to confirm the reasons for the rally in the first place, as another participant stated as well.

The images below are some of my own pictures from the rally. From top to bottom, the images are: 1) Members of a local Unitarian Universalist contingent wearing green and yellow t-shirts participating in the Day of Remembrance and Response; 2) and 3) Participants carrying a variety of homemade signs; 4) Deric Muhammad, local Nation of Islam leader and activist announcing an economic boycott of Waller County, whose face you can make out directly under the red, black, and green NBUF flag; 5) and 6) A crowd entering (again, entering, not storming) the Waller County Jail lobby at the conclusion of the NBUF-led portion of the protest; 7) My own personal homemade signs, etched in Pan-African colors, I carried throughout the day.

***

On Monday, August 10, less than 24 hours after the Day of Remembrance and Response concluded, and on the same day activists delivered petitions to the front of the Department of Justice for a federal investigation into Sandra Bland’s death, a number of us returned to Waller County Jail mid-day to continue holding vigil to ask #WhatHappenedtoSandraBland. Little did we know, the 100 plus degree temperatures would serve as a metaphor since things heated up in the afternoon outside of the jail. Shortly after we arrived, Waller County Sheriff R. Glenn Smith exited the front door of the jail, and confronted Reverend Hannah Bonner, reminding her (and us) to make sure we did not block the entrance to the jail. Bonner respectfully replied that none of the activists and allies holding vigil had ever blocked the front doors in 20 plus days sitting outside of the jail. In a series of exchanges that followed, during which Reverend Bonner used nothing but respectful tones and language, the same respectful tone and language I have witnessed her use during the last month of sitting vigil, Smith acidly said that the protesters showed their “true colors yesterday,” meaning the aforementioned lobby moment on the Day of Remembrance and Response. Smith’s bald attempts to intimidate Bonner, and by extension those of us present (and in effect all allies in this struggle), continued. He walked out to the jail parking lot, took photographs of our cars and license plates, and told Hannah he was “going to do something with them.” Then, as the Waller County Sheriff walked back towards the jail’s entrance—the same Sheriff in whose custody Sandra Bland died—he turned directly to Reverend Bonner and told her, “Why don’t you go back to the Church of Satan you run.” The photo below, taken a short time after Smith’s comments, features some of the sister comrades referenced in this post, along with a local ally. Later in the afternoon of Monday, August 10, those holding vigil asked the sheriff several questions, and another exchange ensued. As reported by the Houston Chronicle on Tuesday, August 11, in additional video footage Smith again referred to Reverend Bonner as the “church of Satan lady.”

Hannah’s recording of Smith’s confrontational comments, shortly after being tweeted and retweeted hundreds of times, went viral starting on the afternoon of Monday, August 10. Huffington Post picked up the story shortly thereafter. On Tuesday, August 11, Cynthia B. Astle, on behalf of the United Methodist Church, composed on open letter to Sherriff R. Glenn Smith. That same day other news outlets picked up this developing story, including the Houston Chronicle, The Independent, New York Daily News, and The Washington Post. Also on Tuesday, August 11, it became apparent that the sheriff assembled barricades in front of the entrance to Waller County Jail, with “No One Beyond this Point” and “No Loitering in Lobby” signs posted. Ashton Woods offered an on-site commentary about it. It also appears that the Waller County Sheriff discarded the makeshift Sandra Bland memorial that had remined untouched for weeks outside of the front door of Waller County Jail. Unable to sit next to the front door of Waller County Jail in peaceful protest, those keeping vigil then assembled under a large oak tree at the edge of the parking lot with lots of shade. Scenes from Woods’ video above shows the tree’s actual size, and how much shade it provided. Astonishingly, after the vigil-keepers left on Tuesday evening August 11, Hannah Bonner reported that the oak tree was cut down.

About the first Smith “church of Satan” video, one supporter tweeted, “Outside a jail a month in a clergy collar and this is the conversation.” Another person commented that the video offered “A glimpse into the #WallerCounty sheriff’s heart. This is what #SandraBland was up against.” After watching the video, a Prairie View professor stated, “I see Waller County Sheriff is living in his continued negativity toward #WhatHappendToSandraBland community today.” Rhys Caraway wrote, “The Sheriff of Waller County is really showing his true self today. Told @HannahABonner to go back to the church of satan that she runs.” A local graduate student, who attended the previous day’s rally, added: “Be clear: “Waller Cty is directing their intimidation at @HannahABonner, but they are doing so *in response* to a crowd of people.” And a fellow clergy member asked, “It makes me wonder: if that’s how he [Smith] treats clergy, imagine how he treats his inmates …???”

***

In the immediate context, there is no question that the case of Sandra Bland adds further impetus to the #BlackLivesMatter movement that has emerged over the last year. From a historical vantage point, there is also much on which to reflect in terms of African American history, most especially in light of conversations conducted in the space of the AAIHS blog.

First, it is powerful to note that a large majority of those holding vigil for Sandra Bland in Waller County are Black women and white female allies—the sister comrades referenced in the title of this blogpost. On the one hand, this speaks to the tragedy of state violence against Black women, a topic that contributors such as Emily Owens, Janell Hobson, and Ashley Farmer have investigated on this blog. On the other hand, it exemplifies a documented longitudinal trend of the power of Black women’s activism and organizing, another subject which this blog has addressed through the posts of Jessica Marie Johnson, Patrick Rael, Kami Fletcher, Ashley Farmer, (and here), Lauren Kientz Anderson, Rhon Manigault-Bryant (and here), Chernoh Sesay, Jr., and Marcia Watson, for instance.

On African American history and literature as intellectual resources in the context of engaged activism, something about which blog contributor Guy Emerson Mount contemplated in his insightful #BlackThoughtsMatter post, those on-site in Waller County have started to assemble a make-shift “library” of books that have provide intellectual and existential sustenance, just as the water and Gatorade have kept everyone physically hydrated. Works by W. E. B. Du Bois, bell hooks, James Baldwin, Audre Lord, and Mumia Abu-Jamal, for example, have delivered food for thought, and content for discussion and reflection. More informally among some of those holding vigil, this small collection has been referred to as the Sandra Bland Memorial Library of Herstory, History, and Culture in honor of Bland’s stated commitment to return to the South in the context of a university setting to carry out Black freedom activities.

Third, and finally, given the substantial presence of clergy—most of whom are Black and white female pastors—who have spearheaded some of the organizing, supported the memory, and celebrated the life of Sandra Bland, we can connect the vigils in Waller County to the history of religion (in this case, Christianity, although other faith traditions, including atheists, have been part of the vigils and actions) and Black freedom struggles. Whether we recall, as referenced above, the expressions of prayer, the Ebenezer, or the daily recitation of Psalm 23 at Waller County Jail from the sister comrades, or inversely, consider the Waller County Sheriff’s comment about Reverend Bonner’s “church of Satan,” as Kami Fletcher, and especially Rhon Manigault-Bryant have reminded us on this blog, religion remains a powerful reserve of spiritual and existential strength in the quest to proclaim the dignity and humanity of Black people.

While the story of Sandra Bland and her death and her memory continues to develop in Waller County, Texas, I wanted in this post to provide a local perspective and present groundwork developments not necessarily represented in national news stories. Yet as we attend to staying current with news stories in today’s 24-hour reporting cycle, very few of which have captured or fully appreciated the local nuances of actions and activism in Waller County, it is vital that we keep history in mind. Referencing the reservoirs of the past—akin to what the late Manning Marable called “living Black history”—sheds critical light on the present as we document and narrate the valiant efforts and persistent struggles of people like Sandra Bland—and her sister comrades in Waller County—who at this very moment, along with many others, continue to #sayhername.

*I thank Carie Cauley and Hannah Bonner for feedback on earlier drafts of this post.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.