We Live for the We: A New Book on the Political Power of Black Motherhood

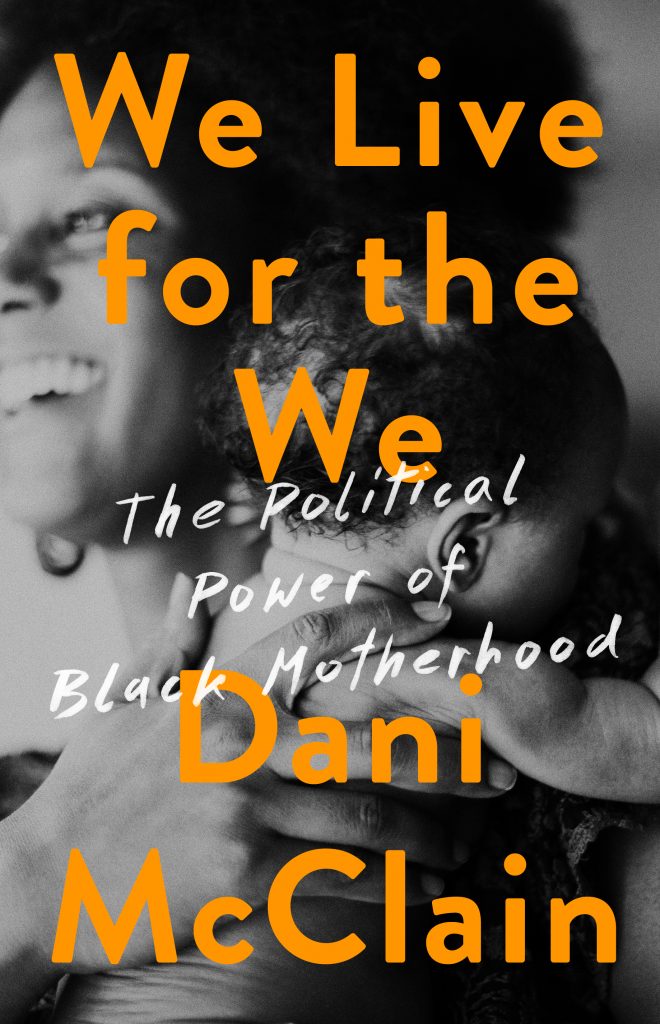

This post is part of our blog series that announces the publication of selected new books in African American History and African Diaspora Studies. We Live for the We: The Political Power of Black Motherhood was recently published by Bold Type Books.

***

The author We Live for the We: The Political Power of Black Motherhood is Dani McClain who reports on race and reproductive health. She is a contributing writer at The Nation and a fellow with Type Media Center (formerly The Nation Institute). McClain’s writing has appeared in outlets including Slate, Talking Points Memo, Colorlines, EBONY.com, and The Rumpus. In 2018, she received a James Aronson Award for Social Justice Journalism. Her work has been recognized by the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association, the National Association of Black Journalists, and Planned Parenthood Federation of America. McClain was a staff reporter at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and has worked as a strategist with organizations including Color of Change and the Drug Policy Alliance. McClain has a B.A. in history from Columbia University and a master’s degree from Columbia’s journalism school. Follow her on twitter @drmcclain.

The author We Live for the We: The Political Power of Black Motherhood is Dani McClain who reports on race and reproductive health. She is a contributing writer at The Nation and a fellow with Type Media Center (formerly The Nation Institute). McClain’s writing has appeared in outlets including Slate, Talking Points Memo, Colorlines, EBONY.com, and The Rumpus. In 2018, she received a James Aronson Award for Social Justice Journalism. Her work has been recognized by the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association, the National Association of Black Journalists, and Planned Parenthood Federation of America. McClain was a staff reporter at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and has worked as a strategist with organizations including Color of Change and the Drug Policy Alliance. McClain has a B.A. in history from Columbia University and a master’s degree from Columbia’s journalism school. Follow her on twitter @drmcclain.

J.T. Roane: Books have creation stories. Please share with us the creation story of your book—those experiences, those factors, those revelations that caused you to research this specific area and produce this unique book.

Dani McClain: In the summer of 2016, when I was pregnant with my first child, I began reporting a story about Black maternal health for The Nation. I talked to public health researchers and Black birth workers (obstetricians, midwives, doulas, and nurses) about why this country has such significant race-based maternal health disparities and what we can do about it. The reporting process allowed me to reflect on my own experiences and consider how they either fit with or diverged from broader trends in maternal care. That same summer, the Mothers of the Movement, whose Black children had been killed by police or vigilantes or had died while in police custody, took the stage at the Democratic National Convention. An editor who knew I’d been slowly gathering string for a book about black motherhood sent me a long email later that night, reminding me that these women’s loss was something quite foreign to mothers who are not Black, particularly white mothers. Meanwhile, many Black mothers live with the fear of losing their children because of white supremacist violence and this country’s general disregard for Black life. I became even more motivated to write about the distinct challenges and joys of Black mothering. I didn’t want to tell a story mired in fear, anxiety, and hopelessness. So I started asking Black mothers and grandmothers who are immersed in political and cultural organizing how they bring their values into family life and pass their optimism and commitment to bettering this world on to their children. I learned a great deal from asking other Black parents my most urgent questions about how to raise my daughter with dignity and joy. This book is the culmination of those conversations.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.