We are our own Multitude: Los Angeles’ Black Panamanian Community

*This essay is republished in partnership with Boom California as part of an ongoing series on Black California.

On a Saturday morning in late October, public workers in downtown Los Angeles block off the stretch of Broadway from Olympic Boulevard to Hill Street. Around 10 a.m., a crowd gathers, donned in blue and red garments, shirts embroidered with mola, white polleras with bright-colored pom-poms, or Panama flags draped across their backs, to celebrate the Annual Panamanian Independence Day Parade. Distant relatives and former neighbors spot each other and greet with air kisses on each cheek. The crowd travels with the parade down Broadway and ends with a battle of Panamanian bands at Pershing Square. By activating spaces like downtown, a small but significant, interconnected community of Black Panamanians made Los Angeles their home.

While some have lived in Los Angeles since the 1960s, many Black Panamanian families moved to L.A. from Panama and other states such as New York, to live alongside African Americans with roots in the American South during the 1970s and 1980s. As they sought housing in areas where other Black Panamanians already lived, a constellation of Black Panamanian families and individuals grew in South Los Angeles, North Long Beach, Watts, and Compton. Decades before they migrated to the United States, their grandparents left countries like Barbados, Jamaica, Guadeloupe, Martinique, and other Caribbean islands for Panama. Like them, they relied on family, friendship, and cultural practices.

Settling into their new city, they moved to affordable homes and several apartment complexes in Compton, including an apartment complex my mother, a canteen cashier at an aerospace company, managed. Known as “The Blvd,” because of its location on Long Beach Boulevard, one of Compton’s major thoroughfares, Black Panamanians came to occupy over half of the complex’s units. Its layout — apartments that faced each other with a communal space in the front and a walkway in the back that led to the next building — encouraged neighbors to interact and kids to play together. On Saturday mornings, music poured from every apartment: Anita Baker, Johnnie Taylor, Ruben Blades, or Tabou Combo. The aroma of fried, sweet platanos and collard greens drifted between the apartments. During the summer, one neighbor sold duros, juices frozen in plastic cups, with flavors like tamarindo, ginger-infused jamaica, and, my favorite, coco, made with fresh coconut milk and shredded coconut, sweetened with cinnamon and nutmeg. If someone had a party, we all partied and feasted on delicacies such as saus (pickled pig feet with onions, cucumber, and white vinegar), chicheme (a drink made with sweetened milk, corn, and cinnamon), and Panamanian tamales (a spicy, reddish masa filled with green peas, peppers, a bone-in piece of chicken, and a prune, tripled wrapped, first in a banana leaf, then wax paper, then aluminum foil). For Nochebuena, my mother made pineapple glazed ham for everyone and rang in Navidad with the songs of Ismael Rivera, Oscar D’León, and Ruben Blades. Though the apartment’s location placed us in the cross-hairs of both gang violence and pedestrian-involved car accidents, we created spaces of joy by sharing Black Panamanian and African-American culture and resources.

On weekends, the Black Panamanian community throughout Los Angeles came together. The physical and social proximity of Compton, Watts, North Long Beach, and South Los Angeles, made it easy to gather in each others’ homes or in local, public spaces. On Saturday afternoons, a group of women, which included my mother, gallivanted to local or cross-town casinos, Compton’s Ramada Inn or Inglewood’s Hollywood Park and Casino, to play bingo. On Sundays, they headed east, out of Los Angeles County, to San Bernardino’s San Manuel Casino. If they didn’t want to drive, they got together in someone’s home, but kept the stakes high and brought their plata. The men played straight dominos in the dining room or backyard or joined the women in the living room, where you could hit on two or three in a row, before winning with the traditional five in a row. Their children commandeered the kids’ room to play video games or listen to hip-hop and dancehall music, growing hungrier as time passed before the evening’s host finished cooking rice and peas (red beans), guandú (also called gandules or gungo peas), or lentils, fried, sweet platanos, stewed chicken, and salad — potato or coleslaw. At times, food inspired the gathering, and someone prepared and sold dinners or fritura, fried finger foods such as hojaldas (a fried bread, also known as hojaldres/dras), empanadas, fried yucca, patacones (twice-fried green plantains), or carimañolas (mashed yucca filled with ground meat then fried). Whatever the occasion, we all ate and ate together.

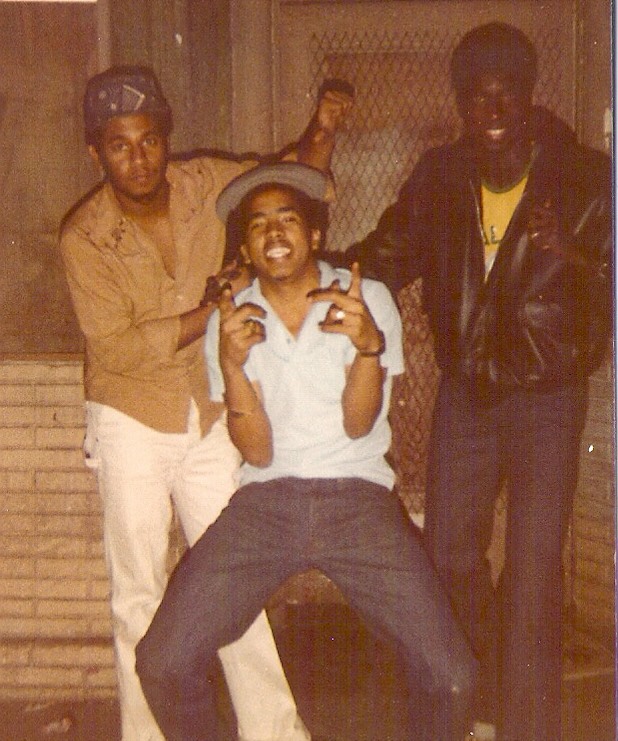

Some Saturdays I accompanied my father to Victor’s Upholstery Shop (known to everyone simply as Victor’s shop); this meant peeking into the shop to say hello then sitting in the car for what felt like hours while my father hung out. Initially located on Washington Boulevard in L.A.’s Arlington Heights, the upholstery shop occupied the corner unit of a large, white brick building, with peeling paint, no windows, and one front metal gate. Named for its proprietor — a slim, brown Panamanian, with a gold tooth and a Caribbean accent (like many Black Panamanians), who often dressed in a natty fit and cap — Victor opened the shop in 1965 and availed his business to the local Panamanian community. For decades, the shop doubled as a communication hub and hang-out spot. If you wanted to confirm information about an event, you called Victor’s shop. If you needed to purchase pre-sale tickets for the upcoming boat cruise or dance, you could buy them at Victor’s shop. When the Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega was ousted in 1989, the local news stations came to Victor’s shop to interview the Panamanian community. The layout of the space itself reflected its many functions. Bolts of fabric lined up like wallpaper on one wall, shelves with binders upon binders of swatches stacked on another wall, and a wide wood work table occupied the center; it sat atop a carpet of wood dust. A dim corner room, across from the work table and behind Victor’s desk, housed a large TV and chairs. The walls were plastered with posters of athletes and bikini-clad women selling alcohol. While the sounds of Victor pounding sofa upsides with a mallet echoed through the shop, the TV room rang with the raucous laughter of men who planted themselves to talk politics and bochinche (gossip) in a mix of Spanish, English, and Patois, drink rum and milk or Cerveza Panama, and watch boxing matches, especially ones that featured Panama’s pride, Roberto “Manos de Piedra” Duran. In exchange, they helped Victor make deliveries. As they aged, they gathered for potlucks and quieter moments.

Across from Victor’s shop was Jucy’s Jamaican restaurant, one of L.A.’s few sit-down Caribbean restaurants, which has operated for over thirty-five years.1 It serves typical Panamanian cuisine like chicken soup with dumpling, stewed meat dishes, and chicken curry. Sometimes we drove down Crenshaw to indulge in a beef patty from Stone Market. Opened in the 1970s, we first frequented Stone Market because it carried typical food items and brands that local stores did not, such as guandú peas, Malta Hatuey (a sweet, carbonated beverage), and bacalao (salted codfish).2 Outside, men sat on folding chairs or milk crates, talking and playing dancehall and old school reggae that you could purchase. Over time, it became a staple in the Black Panamanian community. Located next to the market is the star of the operation: a take-out, cash only, food kiosk, where dinners, patties, and, the best carrot juice I’ve ever tasted, are prepared and sold. It is a small structure, with just a kitchen and front counter, a floor fan circulating heat and noise, and a dry-erase board that displays the menu of the day. Upon entering, the smell of coconut, butter, and cinnamon from the loaves of Coco bread and bun welcomed you the way the cashier will not. What was written on the board is what they had in stock; if an item was marked out or erased, they ran out of it for the day. If it wasn’t on the board, one shouldn’t ask for it (these were the unspoken rules). When an abuelita or other keepers of the homemade bun recipe went on a cooking hiatus, families settled for purchasing buns for Easter or Christmas from Stone Market.

During summer holidays like the 4th of July, we celebrated at Scherer Park in Long Beach. Nicknamed “Parque Del Amo,” for its location off Del Amo, between Long Beach Boulevard and Atlantic Avenue, some families arrived as early as six am to claim one of the limited numbers of picnic tables, while others brought folding tables, lawn chairs, or blankets. Each family prepared meals at home and brought them to the park: cole slaw, potato salad, rice and peas or guandú, baked barbecue chicken, and even hotdogs and hamburgers. Occasionally, my father set up a fryer and sold patacones and codfish cakes. Children would go from table to table to meet-up with friends. Asking for or accepting a plate from a table other than your own was a faux paus; my mother insisted that doing so constituted begging and set the trap for a good piece of bochinche. Folks might say that your mother did not care for you properly. The Scherer Park gatherings grew in size; at one point, someone hired an official DJ and a Panamanian ballet folklórico group performed on a portable dance floor. As Panamanians began to move to cities within San Bernardino County, festivities like an annual end of the summer picnic, were held east of Los Angeles at Frank Bonelli Park in San Dimas.

Parties worthy of a formal venue took place at Shatto Banquet Hall, a rental hall on Slauson Avenue, which was popular among L.A.’s Louisiana Creole community.3 We had our own version of formal wear. For men, it consisted of a button-down blouse, silk slacks, and dress shoes with no socks. Women wore glittered or sequined body-hugging dresses, extra-high heels, and a slather of gold — gold bracelets, anklets, earrings, and necklaces with placas (name plates or plates in the shape of the Panama Isthmus) or an Ojo de Venado (a round ball/amulet wrapped in gold letters). No matter the type of jewelry, it had to be gold, as the women deemed anything else chichipatti (cheap). At Shatto Hall, I witnessed my first and only quinceñera, another second-generation Black Panamanian girl, who body rolled down the two lines of Black damas and chambelanes to Raven-Simone’s rap song “That’s What Little Girls are Made of.”

The predominant narrative about the Afro-Latinx community in L.A. claims that we suffers from isolation and are disconnected. However, it is clear that a network of Black Panamanians nurtured and created a strong sense of identity for the next generation, including myself. As an Black Panamanian in Los Angeles, I was not a anomaly. Instead, I was part of a community that held and named me.

Yet, as the places and spaces known to the community changed, so did the community. Panamanians no longer live on “The Blvd.” Encounters with violence and the lack of opportunity due to divestment and the loss of jobs once provided by large industries, pushed African American and Black Panamanian families out of Los Angeles.4 Many followed the out-migration of African Americans east, to cities like Rialto, Upland, Fontana, and Rancho Cucamonga. Folks no longer gather at Scherer Park. After decades of running his upholstery business out of Washington Boulevard, Victor had to move. This was likely a result of rising commercial rent costs and gentrification. The original location of Victor’s shop is now an art gallery. He retired soon after his shop relocated. Jucy’s and Stone Market have managed to weather the changes and will perhaps benefit from the planned Crenshaw light rail running next to Stone Market.5

While many families moved out of L.A. County, some families, including my own, remained.6 We moved from Compton to Long Beach, and finally, to Watts. My family arrived to these places without the community that once enriched us and made these places home. I long for that community — my mother does too. Now, as a mother, I desire for my children to experience the affirmation that I did growing up in a Black Panamanian Los Angeles. Yet, in the face of change, we remain resourceful and look to the past for guidance. As the child of migrants, I am able to do things that my parents were not able to: I can take my children to Panama. I can take them to the annual parade, the place where we still gather, and introduce them to our neighbors from “The Blvd” and our friends like Victor. Those of us who grew up nurtured by this community of Black Panamanians, and those who are just discovering it, know that in any place we gather, we are our own multitude.

- Linda Burum, “Getting Down Home JAMAICAN,” Los Angeles Times. Sep. 10, 1989. Accessed at https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-09-10-ca-2664-story.html ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Steve Lopez, “As L.A. riots raged, she was shot before she was even born. Now 25, she embodies survival and resolve” Los Angeles Times, Apr. 29, 2017. Accessed at https://www.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-lopez-king-evers-0430-story.html. ↩

- “Natraliart, A Meaty Jamaican Spot in Arlington Heights,” Eater Los Angeles, Jul. 11, 2014. Accessed at https://la.eater.com/2014/7/11/6188189/natraliart-a-meaty-jamaican-spot-in-arlington-heights. ↩

- Lynell George, No Crystal Stair: African-Americans in the City of Angels (San Francisco: Verso, 1992) pp. 239-40. ↩

- Steve Lopez, “As L.A. riots raged, she was shot before she was even born. Now 25, she embodies survival and resolve” Los Angeles Times, Apr. 29, 2017. Accessed at https://www.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-lopez-king-evers-0430-story.html. ↩