W.E.B. Du Bois and the Souls of Academic Folk

*This post is part of our online forum on W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150.

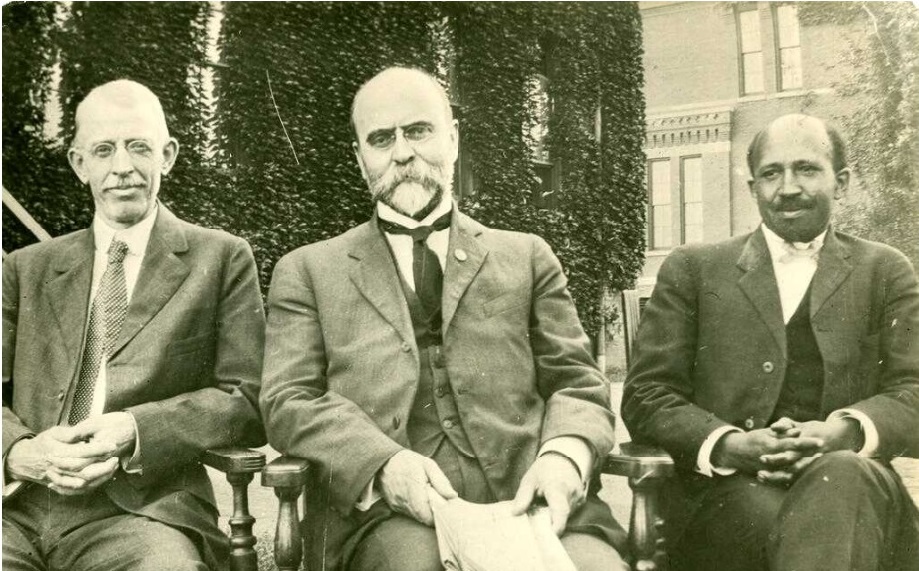

In higher education debates, W.E.B. Du Bois is perhaps best known for his longstanding disagreement with Booker T. Washington over African American education. Although both shared an investment in education for racial uplift, Washington favored industrial education while Du Bois advocated for liberal arts. For Du Bois, investment in liberal arts was not only a matter of educating Black students but also of the roles and responsibilities of academics. Exploring this dimension of Du Bois’s work is essential to recuperating the value of the academic in our contemporary moment.

Disputes over higher education in the U.S. continue to echo the Du Bois-Washington divide. The 2018 State of the Union Address remained quiveringly silent on postsecondary education, except for a call to “open great vocational schools so our future workers can learn a craft and realize their full potential.” This emphasis on professional education echoes ongoing debates over the value of the liberal arts. The nature of academic life is also under siege on a range of fronts. Some have merit, like outrage at the increasing casualization of the professorial labor force, criticism of overproduction of PhDs in relation to available tenure-track jobs, and concern about divides between the “ivory tower” and the public. Others are unreasonable, like attacks on academics from right-wing trolls and fears that universities are bastions of liberal brainwashing. At a moment when what it means to be an “academic” is being called into question, Du Bois offers a clear vision for academics as custodians of knowledge.

Du Bois’s career is an important model for reinventing the category of “academic,” a matter of great importance at this juncture in higher education. With the academic labor force changing drastically through increased reliance on adjuncts, the professorial job market has grown exceedingly grim. The popularity of the term “alternative academic” (or “#alt-ac”) has been one response, encompassing a range of employment opportunities that take advantage of skills gained while earning scholarly credentials. More recently, moves to eliminate the “alternative” in “alternative academic” reappropriates the term “academic” from the professoriate to represent the range of academic work that takes place in libraries, museums, archives, galleries, and non-profit and governmental organizations.

Debates over the term “academic” might amuse Du Bois, whose employment ranged from “traditional” academic work as a professor to “alternative” academic work as editor of The Crisis. During the first half of the 20th century, Du Bois demonstrated that academic labor is diverse and varied and takes place both in and out of “the academy.” As a scholar-activist, he moved seamlessly between the “ivory tower” and the public sector, between university life and advocacy, engaging in the trinity of academic life—scholarship, pedagogy, service—throughout. His nimble leaps between institutions, associations, publications, and even academic disciplines and genres of writing are key to understanding that being a custodian of knowledge is not limited to university professors. These qualities offer a prototype for revisiting the definition of “academic” life.

Du Bois’s hybrid, flexible mode of academic work stems from diverse influences on his intellectual formation. He began undergraduate studies at Fisk University, which left him in no doubt about the value of liberal arts. His time at Fisk cultivated interest in the enterprise of knowledge production, leading him to wonder why there were no Fisk graduates pursuing doctoral degrees at German research universities.1 Du Bois went on to Harvard in 1888 where he was required to repeat part of his undergraduate work before continuing with graduate studies, typical of historically Black college and university graduates of his time. He described himself as “in Harvard but not of it,” foreshadowing a career that wended its way in and out of universities. Du Bois set the lofty goal of obtaining a doctorate in economics from the University of Berlin, which was never realized. Instead, he returned from Germany to complete his doctorate from Harvard in 1895—not an insignificant achievement, as Du Bois was the first African American to receive a Harvard PhD.

An outcome of this varied training was Du Bois’s deep investment in reimagining what academics could do, a task that remains critical to the souls of academic folk. When he took his first teaching post at Wilberforce University in 1894, he strove to “build a great university,” but found his efforts to study African American life unappreciated, particularly in his failed attempt to create an experimental course in sociology. Moving to Atlanta University in 1897, Du Bois realized his goal of fostering ethical knowledge production on African Americans. He turned the university into a center for “systematic and conscientious study of the American negro” through the Atlanta University Studies, which became one of the pivotal moments in his career—like The Philadelphia Negro (1899) and Black Reconstruction in America (1935)—when he made the case for interdisciplinary methods of knowledge production about African American life.2 This was a dream he passionately articulated in 1898 when he wrote:

The American Negro deserves study for the great end of advancing the cause of science in general. No such opportunity to watch and measure the history and development of a great race of men ever presented itself to the modern nation. If they miss this opportunity —if they do the work in a slipshod, unsystematic manner—if they dally with the truth to humor the whims of the day, they do far more hurt to the good name of the American people; they hurt the cause of scientific truth the world over; they voluntarily decrease human knowledge of a universe of which we are ignorant enough, and they degrade the high end of truth-seeking in a day when they need more and more to dwell upon its sanctity.

Du Bois, himself, would become a custodian of this knowledge and foster that sense of responsibility in others, a fitting description of the role of the contemporary academic. His ability to do so was facilitated by the eclectic nature of his education, which disavowed the hyperspecialization characteristic of academic training today. Instead, Du Bois drew inspiration from history, economics, and philosophy, among other disciplines. This is not to suggest that he was a dilettante. Rather, he understood that his prolific interdisciplinary scholarship and writing could play an important role in remaking the world as he set about realizing plans “to make a name in science, to make a name in literature and thus to raise my race.”

Yet, Du Bois knew that being a custodian of knowledge need not be the sole domain of professors, as many academics today are discovering. Even before he left university life to serve as editor of The Crisis in 1910, Du Bois’s experiments in knowledge production already reflected the importance of reaching multiple audiences. Venturing into owning the means of production of knowledge—right down to the printing plant—Du Bois co-founded The Moon Illustrated Weekly in 1905 to promote “self-knowledge within the race.” His monthly, The Horizon: A Journal of the Color Line, which ran from 1907 to 1910, shared Du Bois’s original writing on African American life. He also understood the importance of writing across genres, drafting pageants, short stories, plays, fables, and his much-maligned novels throughout his career. Even his classic, The Souls of Black Folk (1903), blends genres as varied as elegy, autobiography, sociological study, and mythology. These publications were integral to his role as a public intellectual and scholar-activist, both in and out of the professoriate.

Thus, Du Bois was more concerned with contributing to racial uplift through multiple avenues and outlets than doing so from a particular institutional or disciplinary home. He was deeply invested in the intersections of theory and praxis, both his own and his ability to inspire others to join the enterprise of knowledge production on African Americans.

It is here that we can understand the crucial influence of Du Bois on contemporary academic life: wherever we find our institutional homes, we have the opportunity to contribute to human knowledge—particularly for communities that have historically been objects, not subjects, of knowledge. Those of us who received training in PhD programs are familiar with the phenomenon of advisors training us in the way they were taught, for the life they know, endowing us with the lessons of their academic ancestors. However, we must not simply reproduce the conditions of knowledge production in the ways we have been taught. Instead, we must look to Du Bois as an ancestor for another mode of academic life both in and outside universities.

I appreciate this excellent piece, and I like how you contextualize Du Bois’s “hybrid, flexible mode of academic work.” Along these lines, I’ve been interested to learn more about the kind of academic and/or intellectual labor Du Bois carried out through his public lectures, for example, or his “alternative” classroom teaching at the Jefferson School of Social Science during the 1940s and 50s. I wonder if your research studies these sites of labor and unique dimensions of Du Bois’s intellectual work?