W. E. B. Du Bois and the Representation of Black Higher Education

*This post is part of our online forum on W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150.

In a previous post for Black Perspectives, I wrote about the significance of W. E. B. Du Bois’s late career trilogy of novels, The Black Flame, and its connection to the 2015 Charleston Massacre. This is one of many examples of Du Bois’s enduring influence as a scholar and public intellectual. The 150th anniversary of his birth offers another opportunity to reflect upon his life and legacy. While scholars such as Arnold Rampersad, Keith Byerman, and Claudia Tate, have appraised Du Bois’s fiction, there seems to be a resurgent interest in this particular aspect of his writing. A sterling example of the recent scholarship on Du Bois as a novelist and short story writer is the publication of his previously unpublished science fiction story “The Princess Steel,” edited by Adrienne Brown and Britt Russert in PMLA.

My own interest in Du Bois’s work relates to his depictions of higher education. Du Bois is an underappreciated innovator in the academic novel—a genre defined by its fictional depictions of students, professors and university life. From his first fictional experiments, including the serialized story “Tom Brown at Fisk” (1888), to his first two novels, The Quest of the Silver Fleece (1911) and Dark Princess (1928), to his critical analysis in essays such as “Criteria of Negro Art” (1926), Du Bois saw literature as a battleground for representation, and devoted his own creative efforts toward increasing representations of Black higher education in literature and popular culture.

Scholars have written about The Black Flame trilogy—consisting of The Ordeal of Mansart (1957), Mansart Builds a School (1959), and Worlds of Color (1961)—as an historical novel. With a fictional narrative that runs from 1876 to 1954 peppered with real persons and events, the novel is undoubtedly driven by the historian’s chronological orientation. But it is also important to read The Black Flame as a fictional representation of higher education, and Du Bois makes a particular intervention by creating a main character, Manuel Mansart, who is the president of a Black college in Georgia, allowing Du Bois to analyze the realm of higher education as an important aspect of the Black political struggle for equality.

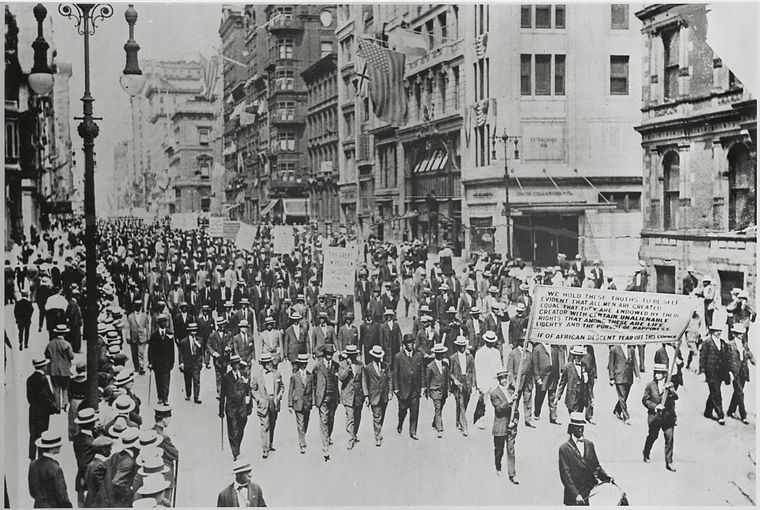

When it comes to Du Bois as an academic novelist, Mansart Builds a School is the most relevant single volume of this trilogy. The novel begins where The Ordeal of Mansart left off, with Manuel Mansart, who was born in 1876 in the violence of post-Reconstruction South Carolina, now a graduate of Atlanta University, and superintendent of colored schools in Atlanta. He is soon appointed president of the newly formed (fictional) Georgia A&M State College in Macon, where he serves from 1920 to 1946. (Though I doubt there was any direct inspiration involved, it is fascinating to see that Georgia A&M is also the name of the Atlanta-based HBCU on B.E.T.’s show The Quad.) These historical markers are important, as Du Bois places Mansart in the events of American and world history, showing his responses to World War I, the Red Summer of 1919, and contemplating the developments of the Harlem Renaissance.

In fact, the chapter on “High Harlem” is an interesting microcosm of this trilogy’s thrilling and frustrating literary form. The chapter shows Mansart’s realization of the cultural developments in Harlem. He is a regular reader of The Crisis, and through the journal he observes the political changes of the New Negro era:

But the Crisis became more than complaint; it was a vehicle of the human expression of the race. It printed pictures of prominent black folk; faces of cunning black babies and of almost all black college graduates who excelled. It printed poetry; it discovered poets; it published stories. Gradually, other journals joined the Crisis: Opportunity from the Urban League; Philip Randolph’s socialist Messenger and the anarchist Challenge. The voice of the Negro became louder and more strident with novels and books of essays. After that blood bath of 1919, the West Indian poet, Claude McKay, burst out in Harlem with the crowning defiance: “If we must die, let it not be like hogs!”

Du Bois is certainly engaging in some self-mythologizing here (he appears in the narrative as the scholar “James Burghardt”), but The Crisis was undoubtedly an important intellectual organ. The above excerpt is followed by a remarkable analysis of the literary and cultural output of the Harlem Renaissance. But by the end of the chapter, Mansart himself resides at the edge of the stage while the narrative addresses Harlem real estate, the internal workings of The Crisis magazine, the first two meetings of the Pan-African Congress, and the NAACP’s relationship to labor.

Mansart Builds a School ends with a passage where Mansart reflects on all that had come before, and on his life’s calling as an educator. He walks across the college campus, affirming the significance of the physical space of the campus as a setting for the hopes and dreams of the race:

[Mansart] wandered sleepless about his college grounds, as so often he had been wont to do in the early days of its beginning when evil lurked. He saw the same stars that shone on Washington, and the mist which started toward them. He believed that beyond the mist burned the Black Flame. How could it be black if it flamed? How could it burn without heat and wild destruction? Yet all this it did, and the dark blaze of its urge as it rolled and roared out of the South bound his heart and world, into one whole of Power and Peace, of Freedom and Law, of Force and Love. But not yet, not for a long, long time yet; and his tears blurred the mist that hid the stars.

This image at the end of the novel, placing the college in an international and cosmic perspective, sets up the third book of the trilogy, Worlds of Color, which depicts Mansart’s evolving internationalism and his global vision of the Black intellectual who lives in a Jim Crow society at home, but sees the potentials for coalition with non-white populations around the globe, in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and Asia. For Mansart, his later tour of Europe and Asia helps him to broaden his intellectual horizons, and to re-consider his understanding of the relationship between capital, labor, and education. He also begins to explore the relations between the white supremacist nations of Europe and the United States, and a broader “world of color” that includes Asia and Africa.

What Du Bois and other Black academic novelists repeatedly address in their work is that the Black intellectual is one who is specifically identified and hailed by white supremacists as biologically and metaphysically incapable of being a scholar. The necessities of racial capitalism under slavery, and in its afterlife, mandated that Blacks be constructed as property, as the raw material for wealth extraction, and not as fully formed human beings capable of equal citizenship or intellectual development. And the academy played an important role in the perpetuation of these ideas, as Craig Steven Wilder elucidates in his important historical study Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery and the Troubled History of America’s Universities (2015). From Notes on the State of Virginia to The Bell Curve, white supremacy has marshaled all of its forces of pseudo-science, revisionist history, and racist theology in order to negate Black intelligence and a Black presence in history, even as, at the same time, it condescendingly admonishes Black people to use education and respectability as a means of upward mobility. The Black Flame is such a remarkable and under-appreciated literary accomplishment because it shows Du Bois using the malleable form of the novel to include historical and sociological commentary on these ideas and creating a counternarrative of Black intellectual history. Collectively, The Black Flame serves as a document of Du Bois’s commitment to the creation of Black art, an attempt to fulfill his own admonition in “Criteria of Negro Art” that Black art is inherently propaganda and ever must be. As literature, The Black Flame certainly has its flaws, but the trilogy constitutes a record of W. E. B. Du Bois as an elder scholar, revisiting the Black freedom struggle, and the narrative arc of his own life, envisioning how far we had come, and how far there is to go.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Hi Professor Porter,

Thank you for writing this informative and scholarly article W.E.B. Du Bois and the Representation of Black Higher Education.

Do you have a bibliography, or at least a working bibliography that you are willing to share with us.

I have clicked through the embedded links, and yet I would like to acquire and fill our library with more of Du Bois’s books.

Thank you again.

Vivica Pierre, PhD, Library Director

Bunker Hill Community College

Thanks for the rich essay. I like how you contextualize the trilogy as an expression of Du Bois’s attempts to use art as propaganda, a creative intervention of arguing that black people are human beings.

As Du Bois is imagining and re-imagining life as a public black scholar and intellectual, I’m interested to know more about how else in the trilogy he depicts the “public labor” of black intellectuals through lectures, journalistic essays, etc. In other words, given Du Bois’s own lecture tours and public talks during the 1950s and early 1960s—at the very same time that he’s formulating and writing the trilogy—to what extent does he creatively depict what’s at stake as a public intellectual?