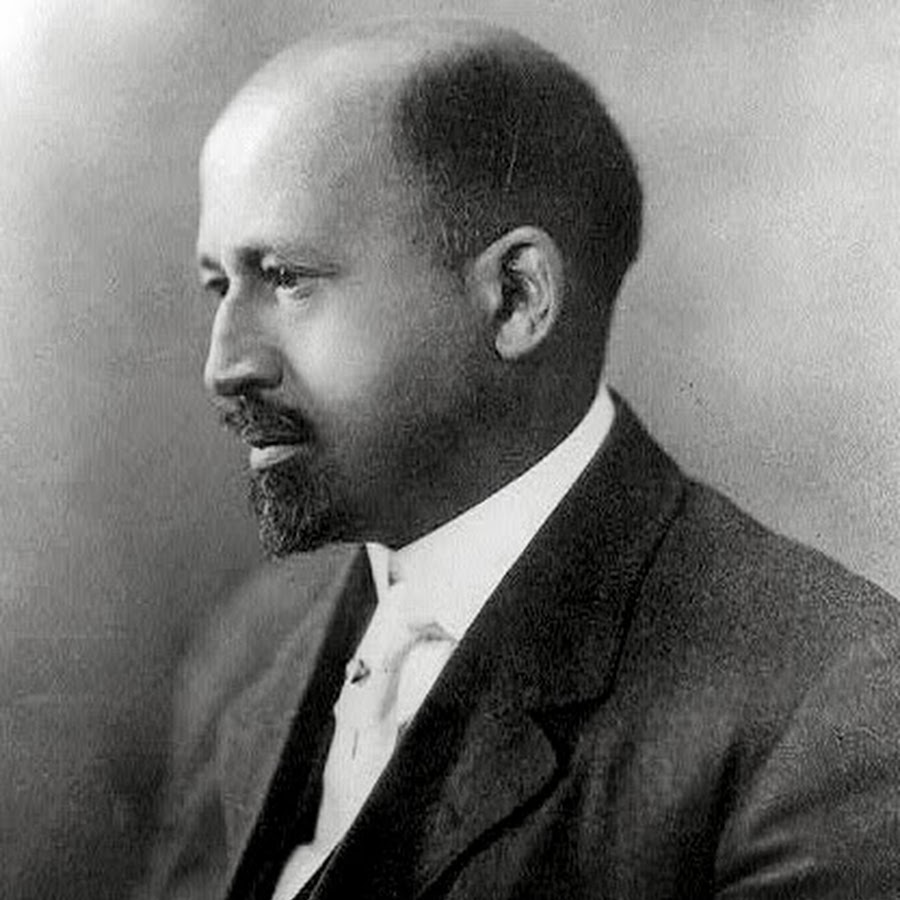

W. E. B. Du Bois, Aesthetics, and the Weird

*Editor’s Note: This week we are publishing our recent online forum on W.E.B. Du Bois in recognition of the anniversary of his passing on August 27, 1963.

The stature and prominence of W. E. B. Du Bois across the many decades of his life as well as the influence of his work in our own time has actually worked to obscure a crucial feature of his writing: its weirdness. The well-intentioned, but often problematic hagiography around Du Bois as well as the canonical status of so many of his works—from The Souls of Black Folk (1903) to, increasingly, Black Reconstruction (1935)—make it difficult for readers and scholars to grapple with the eclecticism and even eccentricity of his prose. For instance, The Souls of Black Folk has long been heralded as a lyrical and prophetic account of the “problem” of blackness in America at the turn of the twentieth century, but it is also a meandering and difficult text, in which Du Bois’s meditative plodding through the dialectics of double consciousness takes shape through a purposely veiled language, filled with its own shadows, opacities, and necessarily half-visible truths.

What would it mean to take the quirkiness of Du Bois’s writing seriously, as well as the influence of a broad range of popular sources on his writing, including pulp genres like horror and weird fiction? This provocation about the “weird Du Bois” is not meant to reproduce Du Bois’s exceptionality (the “eccentric” and the “quirky” as just another way of reproducing a model of Du Bois as unassailable, singular genius), but to connect him and his work to a set of writers, texts, and contexts with which he is rarely associated.

My current project with Adrienne Brown inspires my thinking here: a collection of Du Bois’s short fiction writings tentatively titled The Fantasy Worlds of W. E. B. Du Bois. This volume introduces and collects Du Bois’s sensationalist, action-packed short stories, from the science fiction utopias and feudal fantasies that he wrote in the first decades of the twentieth century to his international(ist) stories about Black love, intrigue, and crime plots during the McCarthy era. Sheree Renee Thomas’s ground-breaking anthology Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora (2000), which included Du Bois’s New York sci-fi disaster story, “The Comet,” first brought his affinities for science fiction to the attention of contemporary readers. “The Comet” originally appeared in Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil (1920), but in our research, we’ve discovered that Du Bois wrote speculative fiction across the entirety of his adult life, including several stories that remained unpublished in his lifetime (and in ours).

Beyond its illumination of the popular and even pulpy dimensions of Du Bois’s essays and academic studies, we follow Mark Jerng’s recent argument that, far from being a marginal body of literature, pulp fiction was itself central to cultural forms of “racial worldmaking” beginning in the early twentieth century. The “weird” is a particularly helpful category for thinking about Du Bois’s short stories. Most commonly associated with the early-century writings of H. P. Lovecraft, weird fiction traverses and mixes science fiction, horror, the gothic, mystery, and colonial adventure in order to make the real feel disorienting, uncanny, and often horrifying. As a genre of the un-settling, the weird reproduced narratives of settler colonialism, racial othering, and raging xenophobia; however, as in texts like Lovecraft’s “The Call of Cthulhu,” the deeply racialized and colonial tropes of the weird could simultaneously glimpse the power and potential of a racialized and colonized global multitude, always on the verge of organization and revolt. Indeed, Du Bois’s short stories—as well as the serial novels of Pauline Hopkins—deserve more attention within a growing body of scholarship on the weird, especially in speculative realist philosophy that idealizes the “non-human” in weird fiction without attending to how racial monstrosity and miscegenation shape the weird’s representation of the human and non-human at every turn.

What else might an engagement with Du Bois and the weird afford scholars and readers? For one, Du Bois’s affinities for “low-brow” culture set his writing apart from the modernist and avant-garde aesthetics that defined much of the Harlem Renaissance. It’s further interesting to think about Du Bois escaping into the impersonal world of pulp fiction-writing and fandom, donning different personas and creating characters in opposition to the work he did to center himself in his non-fictional writings (the Du Boisian mode of rhetorical self-aggrandizement that, even when historicized and contextualized, is difficult to ignore). There is also more to say about Du Bois’s connection to recent work in Black horror, from Victor LaValle’s Lovecraftian-revenge novella, The Ballad of Black Tom (2016), to Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017). For example, “The Comet” might be read as a kind of Get Out narrative set in Jim Crow America. While most of the story traces the post-disaster movements and conversations of protagonists Jim and Julia, a Black man and white woman who think themselves to be the only surviving humans on the planet after the tail of a comet causes mass death in New York City, “The Comet’s” sci-fi and romance frame falls apart upon the discovery of Jim “alone” with Julia at the end of the story. Du Bois’s plot twist thus raises the specter of lynching, the omnipresence of white supremacy, and the rampant policing of Black sexuality in the period.

I have also been thinking about the weird Du Bois alongside the Du Bois who contributed a set of beautiful, colorful, proto-modernist data visualizations to the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900. While The Souls of Black Folk is itself a kind of ghost story, shaped by the tropes of supernatural fiction (“life within the Veil”), the Du Bois infographics utilize clean lines and a modern style to represent Black life in America. The data visualizations contain no shadows or shading, only stark lines and bold colors: a wildly different aesthetics of the color line. While Du Bois’s fiction is fascinatingly “out of step” with Black literature of his own moment, the 1900 data visualizations were purposively forward and future-looking. As part of the exhibitions put on display in the American Negro Exhibit at the Paris Exposition, the infographics sought to imagine a place for African Americans, especially Black Southerners, in the future, in and against Social Darwinist discourses of “race suicide” in this same historical moment.

On their own, the data visualizations are perhaps most exciting because they further illuminate the collaborative work of Du Bois’s school of sociology at Atlanta University, about which Aldon Morris has recently written. In a collection of the Du Bois infographics that is forthcoming from Princeton Architectural Press in Fall 2018 (and co-edited by myself and Whitney Battle-Baptiste, with essays by Aldon Morris and Mabel Wilson), Silas Munro argues that Du Bois headed a Black design team that worked together to create the data visualizations for the Exposition Universelle. This history further illuminates the many “hats” Du Bois wore across his career, but the deeply collaborative nature of the design project simultaneously points to how “Du Bois” is not always reducible to Du Bois as a singular author or agent. Following the work of scholars who have examined Du Bois’s fraught and often appropriative relationship to Black women intellectuals, we might ask: what intellectual networks, forms of labor, and sites of collective enunciation operate under the sign of “Du Bois”?1 What work might further excavate the agents, texts, contexts, and networks that operate underneath the towering name of “Du Bois”? It’s important here to recall that Du Bois’s fiction traffics in the tropes and formulas of pulp fiction—a body of writing that itself privileges the non-original, the multiple, and the collective over the original, the authentic, and the single author.

I do wonder occasionally what Du Bois might have to say about publishing his unpublished work that did not appear during his lifetime. We know he had strong ideas about aesthetics and their role in the world. But it is my hope that the “weird Du Bois” might push us to think more expansively and creatively about Du Bois and his legacy on the occasion of his 150th birthday year. In fact, the celebration of his birth beyond the typical human life span (150 years!) brings us into a sci-fi orbit that I venture to guess would thrill Du Bois himself. We might do well to follow the lines of flight such speculative celebrations invite.

- Joy James, “Profeminism and Gender Elites: W. E. B. Du Bois, Anna Julia Cooper, and Ida B. Wells-Barnett,” Next to the Color Line: Gender, Sexuality, and W. E. B. Du Bois, ed. Susan Gillman and Alys Eve Weinbaum (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2007), 69-98; Shirley Moody-Turner, “‘Dear Doctor Du Bois’: Anna Julia Cooper, W. E. B. Du Bois, and the Gender Politics of Black Publishing,” MELUS 40.3 (2015): 47–68. On the author function, see also Michel Foucault, “What is an Author?” Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology, ed. James D. Faubion (New York: The New Press, 1998), 205-222; Gilles Deleuze and Claire Parnet, Dialogues, rev. ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007). ↩