Upending the Ivory Tower: An Author’s Response

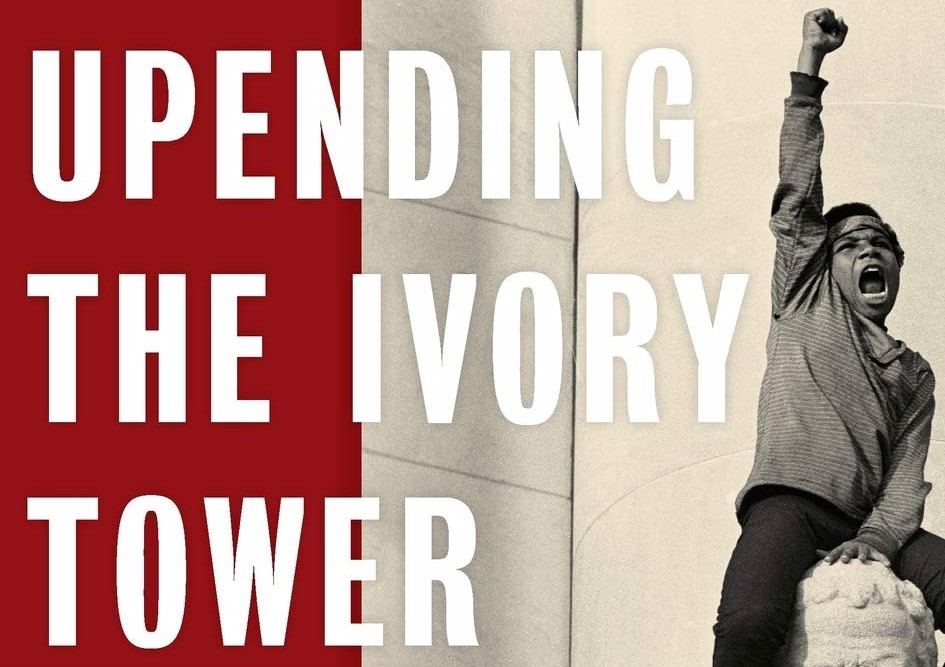

*This post is part of our joint online roundtable with the Journal of Civil and Human Rights on Stefan M. Bradley’s Upending the Ivory Tower: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Ivy League

After researching for Upending the Ivory Tower: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Ivy League, I was not surprised that some parents cheat to get their children enrolled in the Ivy League. The tests, preparatory schools, and legacy admissions were already designed to usher in a certain group of students. The eight institutions (Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Penn, Brown, Columbia, Dartmouth, and Cornell) are not necessarily magical, but they have historically provided a paved path to socioeconomic security and “success” in America. I wrote about what happened when Black people wanted access to those esteemed institutions. Most Black Ivy Leaguers (whether students or professionals) endured othering, overt racism, and paternalism with the goal of creating better life chances for themselves and their communities. The Black Freedom Movement gave them strength in their struggles.

I am so humbled that top scholars Shirletta Kinchen, Alaina Morgan, Jon Hale, and Zebulon Miletsky reviewed the book. Although I learned a great deal when writing, I got much from their readings of my work. In their reviews, several themes emerge. One concerned the agency and audacity of Black youth, students, and alumni of the Ivy League. Another regarded the diversity of Black students and activists who were present in the Ivy league in the 1960s–1970s. How Black Ivy Leaguers viewed themselves and how others viewed them was a theme that arose as well. And, finally, the resilience of those Black students and educators who found themselves in what one anti-Black racist Ivy Leaguer called a “citadel of whiteness” (meaning the university) comprised the last theme.

Prof. Morgan observed that Black Ivy League students of the past and present, along with their mentors, had to lead their liberal institutions toward justice. Righteously, Black learners at each of the Ivy institutions pointed out the cognitive dissonance associated with their liberal missions and their treatment of Black people. Many protested and demonstrated, but some Black students chose to let their presence and academic success be their form of resistance. There was a diversity of opinion as to how to achieve goals of increased Black admissions or end university expansion or establish Black Studies. Students did not arrive in the Ivy League with the same positionality; their approaches to freedom fighting and survival differed. Prof. Morgan suggested that the book let off the hook those students who chose not to participate in disruptive actions. Many Black students, who did not outwardly demonstrate, were sympathetic to the causes of militant students who captured campus buildings or agitated. Within action groups there was disagreements over tactics that nearly crippled campaigns. At Brown in winter 1968, students debated whether to demonstrate in the way that students did at Columbia University the previous spring when activists physically fought police. Perhaps one of the most notable struggles over methodologies occurred within the Afro-American Society at Cornell when firearms were introduced for protection in spring 1969 after a cross was burned at a Black women’s residence. The prospect of fatal violence ignited intense disagreements among progressives. Then, the book spent some time on Black students and educators who outwardly opposed the goals of activist-learners, but a fuller treatment of the Black opposition to campus activism in the vein of Thomas Sowell’s Black Education: Myths and Tragedies (1970) would be a fascinating project.

In addition, Prof. Morgan asked about Black alumni. As individuals and in collectives, they played vital roles in advancing freedom opportunities for Ivy students. Before the late 1960s, the few Black graduates of the Ancient Eight used their positions at private and non-profit organizations like the National Scholarship Service and Fund for Negro Students, the Ford Foundation, and the NAACP; others became trustees. After the push to enroll Black students during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, they formed groups like the Association of Black Princeton Alumni and the Black Alumni of Dartmouth Association. These became lobbying organizations and protectors of enrolled students. Black alumni reported on the student experience and the transgressions of the elite institutions. They showed that the advancement of Black freedom was not just a project for spirited college students but that they too must use their status as Ivy alumni to benefit others.

In her review, Prof. Kinchen emphasized the fact that Black Ivy League students were not a “problem” to be solved; they were solutions to issues of deep institutional racism. I argued that, in some ways, these elite school may have made Black learners and educators better by allowing them access to certain resources; in more ways, however, Black people enhanced the Ivy League with their campaigns for inclusion and justice. Although they were too few to effectively alter major policies in the years before World War II, Black students moved beyond cultural assimilation in the subsequent decades. In a question similar to that which Princeton (and later Harvard) alumna Michelle Robinson engaged in her senior thesis, Prof. Kinchen asked, “What is the responsibility of Black students in elite educational spaces to the Black community?” That query pricked the conscience of many Black Ivy Leaguers. As Prof. Kinchen explained in her important book on Black students in the Bluff City, the grand majority felt an obligation to “open doors” for members of their racial community, whether that meant admissions or access to university resources. That led to protests off campus for the respect of Black neighbors but also on campus to create pipelines for students from impoverished communities. Their efforts tangibly affected the life chances of future generations, including the current classes.

Picking up where Prof. Kinchen left off, Prof. Miletsky points out the role that Black Ivy graduates played as members of what Du Bois and the American Negro Academy referred to as the “Talented Tenth.” Those who could not enter the Ivy League often pinned their hopes and dreams on the few who could. Prof. Miletzky astutely notes that white supremacy confronted Black Ivy Leaguers at every turn. Competing in historic spaces, where the symbolism regularly reminded Black people of their erasure from all things important to the world, was daunting. Still, Black learners and professionals survived and thrived — even while enduring “darky jokes” and dodging urine bombs. They did so by creating community among themselves in the form of fraternities and sororities, as well as Black student unions. From desegregation to Black Power, the organizations reflected the freedom movements of each era. They struggled against what Jeanne Theoharis, Brian Purnell, and Komozi Woodard call “Jim Crow North.” Because of their tenuous acceptance into the schools but exclusion in terms of housing and social activities, Black Ivy Leaguers looked to the local Black community whenever possible. In the pre-World War II years, that meant living with welcoming Black families. At Brown in 1968, that meant staying in an historic Black church as part of a boycott of the university; at Columbia that same year, that meant inviting Harlem residents onto campus to fight university expansion. And at Yale in 1970, that meant collaborating with the local chapter of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. Mostly, however, it meant finding “safe spaces” where they could be themselves. Often those spaces were in the homes of Black professors and administrators like Harvard’s Martin Kilson, who did not always support the protest efforts of students but was willing to provide them protection and home-cooked meals.

Finally, Prof. Hale bolstered a point the book made: the Ivy League evolved in terms of its racial policies not because of the good will of liberal administrators but because of agitation from Black students and their allies. To be sure, good-hearted white administrators eventually acceded to the demands of militant Black and white agitators, but most of those administrators had worked at the institutions for many years and witnessed reprehensible behavior as it concerned Black lives. It took the Civil Rights and Black Power movements to convince decision-makers of the need to change the staid institutions. Prof. Hale highlights the way that the media and administrators portrayed some Black Ivy League student-activists, such as those who took up weapons at Cornell, as unreasonable radicals. I contended that it was not unreasonable for students to protect themselves from violent vigilantes amid a torrential storm of death threats. It was also not unreasonable at Harvard and Yale to demand the universities that took pride in educating the world include Black people in the curriculum by way of Black Studies. Students were as loud and disruptive as they needed to be to dramatize critical issues. At Dartmouth in the late 1960s, circumstances did not require students to take over buildings because they had direct access to decision-making trustees; at Penn, during the conflict of university expansion, it took protest actions to even get a meeting with the president and eventually the trustees. These nuanced tactics are informative for contemporary activists, who are searching for the most effective ways to steer American institutions and systems toward justice. As youth seek to advance freedom for Black people, they must defend the gains of the past. Those young people should draw inspiration from their forebearers’ efforts. I hope that Upending the Ivory Tower can help.

The four incredible scholars who reviewed Upending the Ivory Tower provided me some solace because they not only perceptively extrapolated my arguments, but they embraced the book’s meaning. Life in higher education changed for the better because the most marginalized students at the most privileged institutions chose to act. For that, I am eternally grateful.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Thank you to all of those who have contributed to this round table discussion. You have modeled how to engage and challenge how we imagine and share history as a collective. This is a model that our students and our colleagues can learn much from. Thank you.

Stefan: Good to see that you are still at it! Got notice from Yusuf Nuruddin list. Are you still promoting our DVD along the way? I have a copy to give you and sell $20 to cover duplication and postage.

It is on Youtube in 3 parts under Black Columbia, Part I, Part 2, Part 3.

VALA : The Power of Black Students at Columbia University, 1968-2008

Sherry A. Suttles, Producer; Co Kamau Suttles. Shown at the 40th anniversary, purchased by NYU $100; shown at San Diego Black Film Festival 2009 and other avenues of distribution.

Produced 44 Daze: Managing a Community under Worldwide Crisis-Trayvon Martin & the City of Sanford,FL

and producing a third documentary: Coloring of America’s Cities: Emergence of African American City Mgrs.