Uncovering the Voices of Working-Class Black Women in Harlem

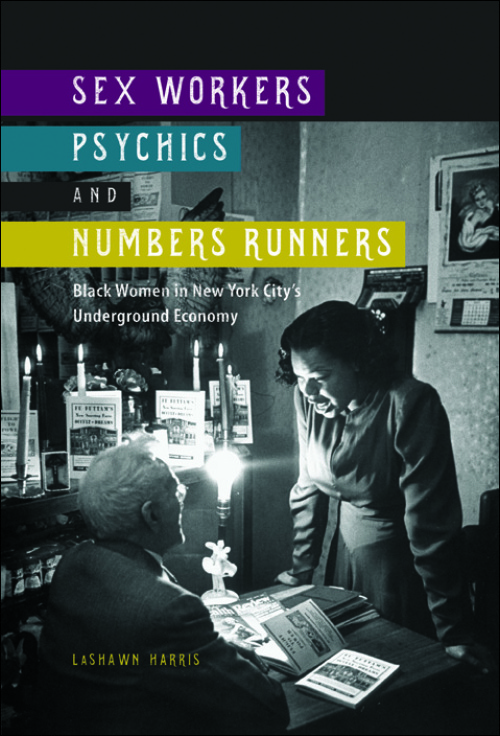

Today is the second day of our roundtable on LaShawn Harris’s new book, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy (University of Illinois Press, 2016). On Monday, blogger Keisha N. Blain introduced the book and its author. Dr. Harris is an Assistant Professor of History at Michigan State University. Completing her doctoral work at Howard University in 2007, her area of study focuses on twentieth century United States History. Harris has recently published articles in the Journal of African American History, Journal for the Study of Radicalism, and the Journal of Social History. Her first book, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners, examines the public and private lives of an all-too-often unacknowledged group of African American female working-class laborers in New York City during the first half of the twentieth century.

In today’s post, Julie Gallagher provides a general overview of the book, highlighting its contributions to the fields of African American, women’s, labor, New York and urban history.

New York City. Harlem. We know these places. They are familiar to those of us who walk its streets and study its history. We see the buildings and the people and we think we understand. We pass the storefront churches. On a bad day, we may contemplate a tarot card reading, hoping for a promise of a better future. And sex work – prostitution – the “oldest profession,” we recognize it too. And then a book like LaShawn Harris’s Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy comes along and we realize how much more there is to learn. How much richer the history is. How much more complex and nuanced the world around us is. That is what an excellent book can do, and that is what Harris has given us. She has dug deeply in a number of archives, has read broadly across disciplines to bring in multiple analytical voices, and most importantly, she has recognized and given voice to the humanity buried in the anti-vice reports and the sensationalist headlines.

Throughout the course of her book, Harris reveals urban black women’s determination, human agency and resistance, fear, pleasure, longing, creativity, flexibility, and depravity. Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners is not only a tremendous contribution to the fields of African American, women’s, labor, New York and urban history, it is also a powerful reminder that we must listen to the silences, read not just with but also against the grain of sources, and resist the temptation to settle for pat answers or simple conclusions.

Set in early twentieth-century New York City, Harlem’s energy, allure, perils, and promise are palpable on the pages of Harris’s book. Black New Yorkers, those who had grown up in the city as well as the many more who migrated from the South or the Caribbean “unapologetically and constantly refashioned and used urban public and private settings as they saw fit” (30). But there were also constant reminders of pervasive discrimination, low wages, and poor living conditions that plagued those hemmed in by Jim Crow residential practices and white supremacist ideology.

Set in early twentieth-century New York City, Harlem’s energy, allure, perils, and promise are palpable on the pages of Harris’s book. Black New Yorkers, those who had grown up in the city as well as the many more who migrated from the South or the Caribbean “unapologetically and constantly refashioned and used urban public and private settings as they saw fit” (30). But there were also constant reminders of pervasive discrimination, low wages, and poor living conditions that plagued those hemmed in by Jim Crow residential practices and white supremacist ideology.

In this context rife with possibilities and limitations, many black women pursued work in the urban informal economy. Harris effectively demonstrates in every chapter of the book, that we cannot make assumptions about why women did this or what they thought about it. Working as numbers runners, psychics, unlicensed street peddlers, or sex workers, many black women sought to gain some degree of control over their own labor, to make money, to fulfill their sexual or personal needs, to provide for their families, or to avoid the job niche they were expected to fill, that of domestic work.

Emphasizing the humanity of these women, Harris remarks that “urban women saw beyond the economic benefits of underground entrepreneurship and yearned for the intangible rewards and privileges of independent work” (35). More than a few paid a steep price for their choices. The work could be dangerous, even deadly. They risked their reputations – public and family shame. They chanced arrest. And sometimes their entrepreneurial efforts resulted in failure. But most weighed their options in a world circumscribed by racial and gender discrimination, and made their decisions consciously, if not always eagerly.

In three case-study chapters, Harris explores black women’s labor in the illegal but pervasive Harlem numbers game, in the world of supernatural entrepreneurs, and in sex work. In Chapter Two, for example, Madame Stephanie St. Clair not only works the numbers game, she is the “Numbers Queen.” As a result of Harris’s extensive and painstaking research, we learn of a woman who defied every convention. The public spaces of the city streets were deeply male, but St. Clair dominated. She was a fierce race advocate. This was clear not only in her promotion of racial uplift, but also in the testimony she gave at a hearing intended to jail her for her illegal business dealings. Without fearing reprisals, she charged the police with racial bias and brutality. She had middle-class sensibilities and projected “proper outward images of black womanhood” (84). Yet, ever the independent and determined business woman, she promised to kill white numbers boss “Dutch Schultz” when he threatened to encroach on the black-run Harlem numbers game. Harris simultaneously offers a picture of a thoroughly captivating historical figure in St. Clair, and uses her story to reveal that women were employed everywhere in the city’s illegal gambling world. They used their work to advance their “socioeconomic and political agendas.” In doing so, they avoided working in white-owned businesses where they would likely face racial discrimination.

Women who entered the informal economy to take up work as supernatural consultants, clairvoyants, crystal ball gazers, tarot card readers, hypnotists, numerologists, and magical healers populate the pages of Chapter Three. Harlem spiritualist Dorothy “Madame Fu Futtam” Matthews, radio evangelist Rosa Artimus Horne, and medium Madame Patsy Taylor and many others created new occupational identities and entrepreneurial opportunities for themselves. Along the way, they became not just economically self-sufficient, but sometimes wealthy as they offered consumers something to hope for, an elixir, or the notion that they could change their life troubles. Urban black women who worked in this dimension of the informal economy defied the demeaning constructions of black womanhood perpetuated by white newspapers, white reformers, and white politicians who suggested that black women were “lazy, licentious, unintelligent, and outside the scope of true womanhood.”

Etched on storefront windows and declared from the pages of newspapers, these supernaturalist entrepreneurs situated themselves as powerful and all-knowing (97). Harris demonstrated that these savvy businesswomen sometimes strategically deployed images and stereotypes of people of African descent and connections to black magic to sell their products and promote their businesses. What was particularly compelling in Harris’s discussion of supernaturalism was her opening and closing of the chapter with contemporary examples of how prevalent this informal and also more formalized economic niche is today. As a case in point, Harris profiled “Miss Cleo,” a self-proclaimed Jamaican “shaman” who offered spiritual guidance via infomercials and $4.99-per-minute phone calls. She and the Psychic Readers Network, for whom she worked, were eventually charged with fraud by the FTC. Nevertheless, Harris appropriately reads “Miss Cleo’s” work as part of long tradition of African American women who made their living by dispensing supernaturalist-inspired advice to those desperately in search of spiritual guidance.

In Chapter 4, Harris builds on the important work of Cynthia Blair and other scholars who are bringing much-needed attention to black sex workers’ wide-ranging experiences. Despite the challenges posed by using sources crafted by those who policed, endeavored to reform, or who reported in lurid detail on women in sex work, Harris does a masterful job creating a nuanced portrait of the sex trade and the women who worked in it in Harlem. She effectively reveals the myriad reasons women entered sex work. While “family and community obligations forced many working-poor black women into the urban sexual economy,” others went into it from a profound desire and passion for sexual pleasure and fulfillment. For example, “married housewife and occasional sex worker Martha Briggs interpreted sex work as a path toward economic independence from her unsuspecting breadwinning husband and conceivably as a path toward sexual fulfillment and experimentation” (137). Harris also captured the complex feelings women had about their sex work. Some felt profound shame and hid their work from family and friends. Others were unconcerned about maintaining a low profile or charges that they undermined racial uplift efforts that relied so heavily on black women’s embodiment of respectability.

Harris further elaborates on the various ways black women experienced sex work – as street-walkers, in brothels, in residences, with black and white men. She grapples with the very real dangers they faced, and the strategies they deployed to manage them, which included sharing information with others in their trade and moving off the streets. Harris reveals these women in all of their human complexity – bringing to the surface their goals and ambitions, their fears and longings, their vulnerability and determination.

Harris’s final chapter demonstrates that black women’s labor in the informal economy was met with constant, if not universal or monolithic resistance. Many working-class and middle-class black residents, reformers, parents and neighbors organized, petitioned, wrote complaint letters and did all they could to remove those elements – vice, troublesome neighbors, the operation of illicit or unlicensed businesses – that they felt undermined their strivings for respectability and efforts at racial uplift. While they their efforts cannot be declared successful, (many of the same elements of the informal economy persist today), their activism nevertheless “underscored broad visions of city life, social mobility, community protection, and public propriety” (200).

In sum, we are in LaShawn Harris’s debt for this excellent, rich, and insightful history of black women and New York City and for demonstrating that there is still so much to learn from those voices, especially those of black women that have been historically marginalized.

Julie Gallagher is an Associate Professor of History and Women’s Studies at Penn State Brandywine. She received her PhD in History from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. She is the author of Black Women and Politics in New York City, published by the University of Illinois Press in 2012 (reprinted in paperback in 2014). In this book, she traces the evolution of African American women as political actors in various roles – as activists, as voters, as appointees, and elected officials – across seven decades. Follow her on Twitter @LSGallagher.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

I am very interested in exploring the presence of black women who incorporated diasporic styles of magic/supernaturalism and entrepreneurship with spiritual practices. I think it is an urban tradition exemplified by Mme. Marie Laveau in New Orleans, Leafy Anderson in Chicago, and culminating with the Jamaican-born Dorothy Hamid in New York City. These women also offered a powerful alternative to the propriety politics and gendered bourgeois sensibilities espoused in the theologies of the traditional Christian churches. Thanks LaShawn for your multi-faceted work, it’s inspiring.