Uncovering New Sources for Research on Black Religion

This post is part of our online roundtable on Judith Weisenfeld’s New World A-Coming

Judith Weisenfeld opens her book New World A-Coming with information gleaned from a federal draft registration card. In 1942, when Moorish Science Temple member Alec Brown Bey registered for the draft, he did not consent to any of the racial categories printed on the card. Instead, he identified his race as Moorish American. Similarly, Weisenfeld concludes her significant examination of Black religion and racial identity during the Great Migration with another government document: the 1929 death certificate of the Moorish Science Temple’s founder, Noble Drew Ali, which recorded his “color or race” as “American Black.” In a testament to the import that such official government classifications have even decades later, Weisenfeld describes the 1992 request of a Moorish Science Temple sheik seeking to correct that death certificate to reflect Drew Ali’s preferred designation, “Moorish American.”

Throughout New World A-Coming, Weisenfeld examines a wide array of government records, including naturalization forms, census records, and marriage licenses, that document the lives of members of the Moorish Science Temple, the Nation of Islam, the Peace Mission, and several Ethiopian Hebrew congregations—religious organizations that actively redefined the racial identities of their adherents. Her close examination of this practice and her introduction of the concept of “religio-racial” identities, or identities “constituted in the conjunction of religion and race,” are important contributions to the field (5). Her use of government records to document the significance and prevalence of these identities is an equally consequential contribution, and it allows her to fulfill the goal of documenting members as they “enacted the identities they understood to be their reclaimed true ones in daily life” (5).

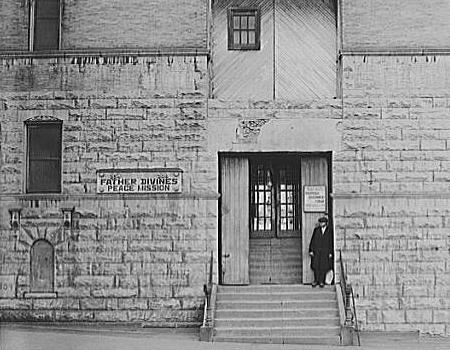

In seeking to understand the lives of these groups’ members, rather than those of religious leaders, Weisenfeld encounters a challenge faced by many scholars studying Black religion during the Great Migration—the lack of extant sources. She compellingly engages with available archival collections, the observations of an earlier generation of social scientists, FBI files, court documents, and newspapers, but she also finds much of interest in seemingly mundane bureaucratic federal, state, and local government records. While she is not the first scholar to examine such sources, Weisenfeld brings to her study of them a new appreciation and creativity. It is worth noting that her use of these materials is not about “big data” or the type of aggregation and mapping that has garnered much recent attention in the digital humanities. On occasion, she takes a broader view of government records—as she does with the 1940 census to document the geographical presence of the Peace Mission and its followers in Harlem—but this is not the primary role of records in New World A-Coming.

Weisenfeld uses government records to recover aspects of the individual lives of adherents that might otherwise be lost to the historical record.1 Through these government forms we learn of Moorish Science Temple members Cleo Caldwell Bey and Eva Johnson Bey, who married in 1929, and who both identified as “olive” on their marriage license. We learn of Happiness Happy Eli, formerly Sarah Daniels, whose petition for naturalization was refused because she would not “affirm that she would bear arms in defense of the United States,” in keeping with the Peace Mission’s objection to taking the life of another (230). We learn of Nation of Islam members Mattie Mohammed and Ocier Zarrieff, married by a Christian minister, and of Allar Cushmer and Beatrice Ali, married by a county judge; both couples desired legal recognition of their marriages “even as they rejected the authority of the U.S government” (181). These records sometimes provide limited glimpses into the adherents’ lives. At other times, Weisenfeld follows individuals throughout a series of records, offering not merely genealogies or histories, but gleaning information about religio-racial identities and religious practices more broadly. She also demonstrates the adherents’ degree of commitment to these religio-racial identities, even when they faced the scrutiny of government officials. She recognizes these transactions as “race-making and maintenance events” (282) and rightly observes the power dynamic in these moments when “members of religio-racial movements challenged the state’s power to categorize them and define black identity” (20).

There are moments when additional context about the practice and collection of government records would complement Weisenfeld’s analysis. Referring specifically to Alec Brown Bey’s interaction with draft registrar George Richman, Weisenfeld acknowledges, “we can never recover the details of this bureaucratic and interpersonal transaction…” (2). And yet, a closer examination at the staffing of the April 1942 draft provides some insight into the interactions between registrants and registrars. To accommodate the men who registered in a matter of days in April, the federal government relied on volunteer registrars. The New York Times reported that in New York City alone, there was a pool of 45,000 volunteers supplemented by public school teachers and fire department staff.2 This broader context does not undermine Weisenfeld’s claims nor does it alter the power dynamic inherent in an encounter with an individual serving (however temporarily or voluntarily) as a representative of the federal government. It does, however, allow us to better imagine how and why registrars documented religio-racial identities in different ways and why this particular group of records proves so rich for Weisenfeld’s study. In addition to the pressures of moving through a large number of registrants quickly (which Weisenfeld notes), temporary volunteer registrars may have been more likely to accept and record religio-racial identities than full-time government officials with extensive training on federal policies and procedures.

It is also worth looking more closely at the sample of the population that the April 1942 draft represents. In the introduction, Weisenfeld explains that this fourth draft registration was for males age 45 to 64. This fact bears repeating as it demonstrates that these responses are from a sample restricted by both gender and age. Again, this context does not undermine Weisenfeld’s use of these materials, but does merit some comment about the role of age and gender in this particular set of records and its documentation of religio-racial identities. Given that the cards from the first three draft registrations are inaccessible due to privacy restrictions, Weisenfeld is not able to offer a comparative reading from a younger population sample. She does, however, turn to other sources that offer insight into the experiences of younger men like Moorish Science Temple member Eddie Stephens Bey, who was drafted into the Army in 1941 and refused to adhere to certain aspects of Army dress on religious grounds.

Weisenfeld also identifies sources that reveal “the strong presence of women as members of the religio-racial movements” (20). In addition to newspaper reports and archival materials, Weisenfeld uses marriage certificates, divorce decrees, census forms, and health department citations to better understand the daily lives of women within religio-racial organizations. Indeed, she documents women “in positions of leadership and authority, despite the fact that all of the religio-racial groups [she] examine[s] were founded by men.” (20) Using these materials, she provides a nuanced understanding of community formation and how it could be simultaneously constructive for the participants and devastating to family members or friends outside of religio-racial communities. She documents how families were broken apart while also pointing to the new opportunities that religious organizations provided their adherents. This broader examination of community is, of course, not restricted to the lives of women, but it is this shift away from a singular focus on the “promulgation of official theology” that creates an opportunity to document women’s experiences within these organizations in a new way (20).

Weisenfeld’s innovative use of government records is just one of many contributions New World A-Coming makes to the study of Black religion during the Great Migration. Her research in this particular set of materials has allowed Weisenfeld to access the lives of people who are compelling exemplars of how these religious organizations shaped the religio-racial identities of their members. Her methodology offers a way forward for scholars studying religion during this period as well as for those in other fields in which archival resources are lacking. In recognizing the significant capacity of government records to help recover experiences of people underrepresented in extant archival material, Weisenfeld’s work should also serve as a call to engage more proactively in conversations about how these records are preserved and made accessible.

- State and federal records have also proved an important resource for documenting the early lives of charismatic religious leaders during this period, as Weisenfeld does for Noble Drew Ali. For an earlier example, see Jill Watts, God, Harlem U.S.A.: The Father Divine Story (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992). ↩

- “13,000,000 Registered in 4th Draft, Including 911,630 in New York City,” New York Times, April 28, 1942, 1, 10. ↩

I am intrigued to know how Weisenfield engaged the community archive of these various organizations

Thanks for the question, James. I also used coneventional archival materials and other material culture and textual sources that came from within the communities themselves, to the extent that there were things available from the period the book covers (1920s through the 1940s).

I wonder how much has been lost due to a lack of archival process? One of the things Deaf studies and history confronts is that most Deaf people have hearing children who may or may not see historical and cultural value in things like old school yearbooks for Deaf schools that have been closed, newsletters, meeting minutes, etc. from now defunct Deaf clubs, and other such artifacts. Or at worst, have a contentious relationship with Deaf culture having never resolved the ’embarrassment’ of having Deaf parents in a time when Deaf culture and signed language was more stridently marginalized in American society. Thus these things that provide glimpses into everyday Deaf life are being tossed into dumpsters.

I’m wondering if a similar erosion of information access shows up in instances where these religio-racial groups are declining in membership in some cities and areas to the point where a temple or mission closes. Where do the records end up? If they end up in someone’s attic, is knowledge of their historical value there in the family to know not to simply toss it out as “that thing grandpa was involved in.” Particularly if it’s seen as ’embarrassing’ in some manner to a descendant who is not part of these movements?

I think these sort of dynamics with archival materials and sources create an urgency for the type of scholarship Weisenfeld has done here, if only to get things into a secondary source format before they ‘disappear.’ This might become an impetus for more of what publications like the Journal of Africana Religions has done with ‘original source’ publication. Not only to give a wider audience to critical source material, but to extend it’s life as a source. That said, a special issue of something like draft cards wouldn’t be all that compelling publishing! But a special issue of selected newsletters from a local chapter of a religious movement with some editorial commentary would be potentially captivating.

I’m thinking of my own research that went back through newsletters of a now defunct Deaf Methodist Church in Chicago and I found all sorts of interesting patterns by seeing what issues they identified as important enough for inclusion, what sort of ‘new ministry’ things they were trying, what sort of social events they were holding, etc. While I have two boxes of index cards with notes that I’ve turned to at times to analyze, I’m now thinking about some sort of ‘curated and annotated reprint’ of this sort of content as a means of preserving and amplifying it.

Another really thought-provoking response, Kirk. I think one of the factors regarding archival preservation is lack of confidence and trust in what outsiders will do with the materials. These are communities that have been subjected to all manner of surveillance, policed, jailed, ridiculed, and more, and I don’t blame them if they choose to keep control of their historical resources. My research benefited from the work some groups do to interpret their materials and histories online, from resources people from some of the groups shared with me, and from the work archivists (particularly at the Schomburg Center and Emory) have done to collect and preserve textual, visual, and material culture resources.

I also find the foregrounding of primary sources with editorial introductions a compelling format, which I used a bit in The North Star, online journal of African American religious history I edited in the late 1990s and early 2000s (https://www.princeton.edu/~jweisenf/northstar/index2.html). We featured only a few of these (https://www.princeton.edu/~jweisenf/northstar/archive.html#documents), but I loved the possibilities they opened up. I’m all for people doing more of this in all sorts of fields!

Ah yes. The historical and contemporary surveillance is a factor not in my calculus on Deaf history. Thank you for the reminder of that.

Digitizing projects also open the possibility of online publishing formats that would allow for collaborative foregrounding as well.