Transcending Time: Centering Literature at Festac 77

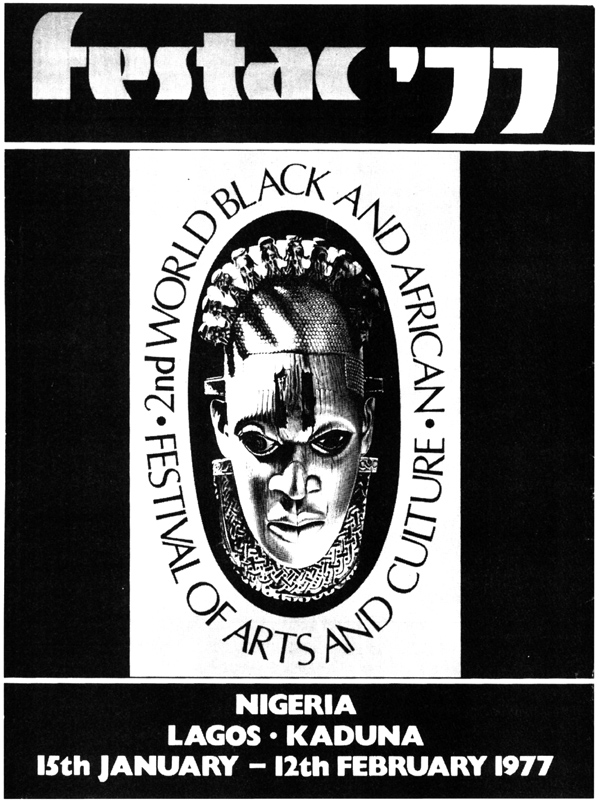

In January 1977, a month-long celebration of African diasporic culture brought participants from fifty-five countries to Lagos, Nigeria, including several hundred representatives of the United States. In an earlier post, I discussed the importance of the events in the fight against global white supremacy, but Festac also represented a broadening of focus within Afrodiasporic studies itself.

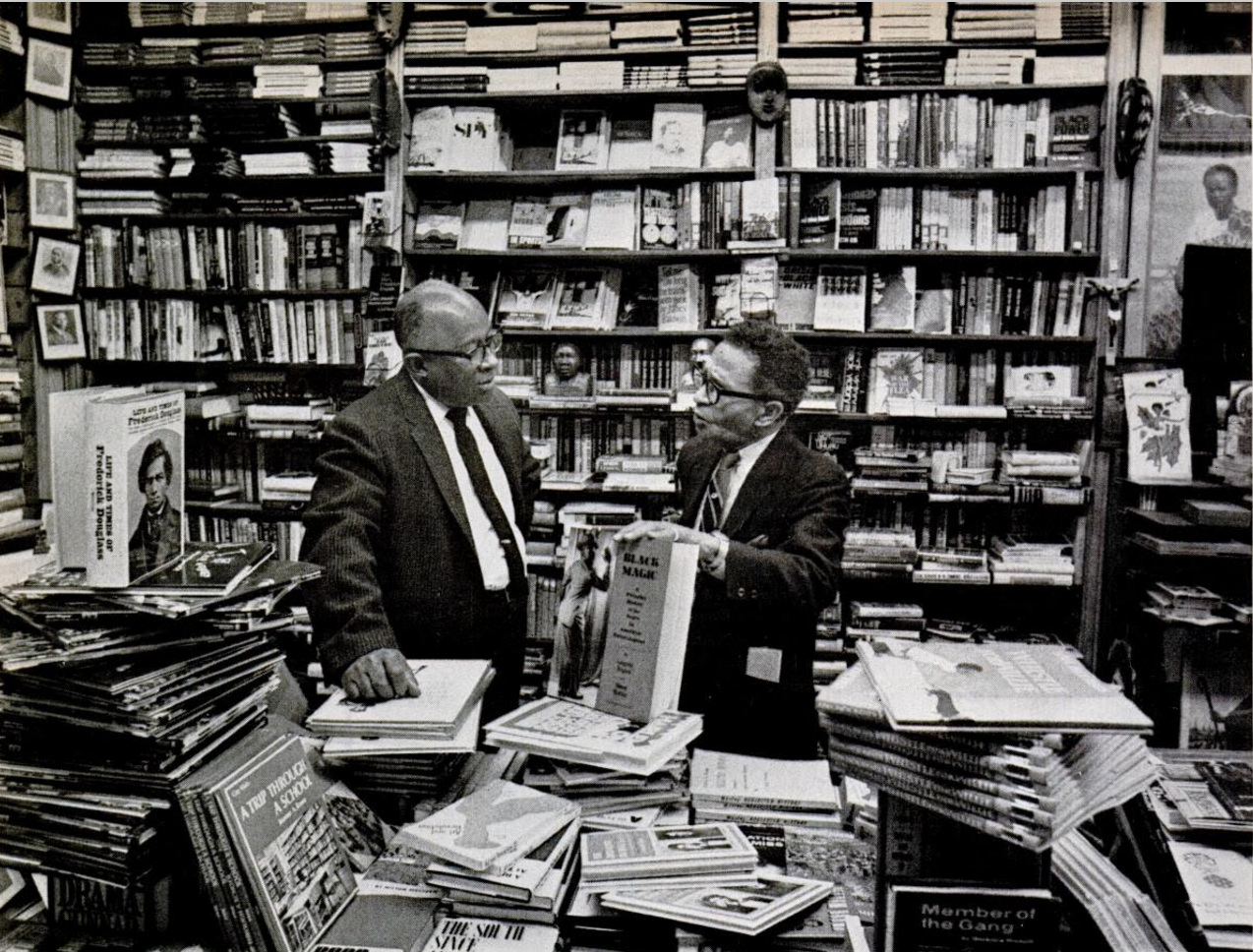

A decade before the American delegation descended on the specially constructed festival town, Clarence LeRoy Holte was emerging as the new Arthur A. Schomburg. In 1970, the latter was a household name in erudite American circles—the namesake of the New York Public Library’s distinguished Schomburg Collection, having sold his 10,000 books on black culture to the Carnegie Company. Holte was just years away from reaching a similar status. By day, he worked in a Madison Avenue advertising agency, designing ads as the resident “ethnic market specialist.” His evenings and weekends, however, were devoted to his true passion: collecting rare books.

When Ebony ran a profile of him in 1970 to highlight his illustrious collection, Holte, without any form of sponsorship, had amassed 7,000 books on black life in America, Africa and beyond, past and present. His mid-sized Washington Heights apartment was bursting at the seams, filled with rare books that had never been printed in the U.S. or of which the majority of copies had been destroyed in Africa’s civil wars. Like Schomburg, Holte assembled a collection “designed for scholarly research,” yet there is no library named after the “soft-spoken” man who once ran afoul of W.E.B. Du Bois for asking him to sign three full sets of first editions of his oeuvre (Quoted in Ebony, Du Bois wrote “I autographed your books because I thought it was the request of a friend who wanted the books for his own library. I realize that this is a commercial undertaking. I will autograph no more books,”). In April of 1977, Holte sold his entire collection—by then consisting of about 8,000 volumes—for a sum of $625,000 to Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, Nigeria.

That the “ambassador with books” would sell his life’s work in whole to a Nigerian university is astounding in and of itself. What makes it even more astounding is that the books had already been in Nigeria for four months, catalogued, crated, and shipped there by a team of organizers for Festac. This attention to literature of the diaspora was new for all parties involved. Nigerian playwright and poet Wole Soyinka had recommended Holte’s collection to festival organizers, and in July 1976 a representative visiting Harlem wrote a “favorable report,” cementing Holte’s participation.

While the festival was intended to celebrate unity and pride, the narration of Holte’s participation displays wrinkles within the community. Holte’s private library came as a godsend to the international festival committee after “many African intellectuals—writers, in particular—felt not enough attention had been given to their craft” at the first world festival in 1968, held in Dakar, Senegal.1 This snub was the reason Nigeria’s literary darling—Chinua Achebe—refused to participate in the 1977 edition. Holte extended this critique to the American delegation, proffering that “it is very significant that American Blacks have an opportunity to participate in Festac in roles other than the traditional ones. It brings about a broadening of the interest of Afro-Americans whose interests transcend the usual ones manifested in the performing arts.”2

Holte’s participation should be read as part of a new and vigorous interest in literature and its political potentialities that crystallized in the U.S. in the Black Arts Movement. Maulana Karenga’s rise to the position of U.S. delegation leader and Jayne Cortez’s prominence at the readings, gesture toward the fact that for part of the American delegation, Festac was the site for radically centering literature as part of a wider political project. Karenga observed, during a keynote address at the festival’s colloquium, that the “faults and fears” that threatened to sever “Afro-connections” could be restored by a robust transnational cultural archive, with a key role for literature. This archive could serve as a “bridge to the non-elite.” This is where Holte and his collection came in. As Adolf Reed has observed, the late 1970s were marked by profound anxiety over the expansion of a managerial and administrative black middle class which threatened to irreparably fracture the black community in the U.S. Literature was perceived as the cement that could hold together or reconstitute a community that was increasingly variegated in its realities.

Despite these internal divisions, however, when it came to literature, the U.S. stood out at Festac. The U.S. ambassador to Nigeria, Donald B. Easum, had requested in a classified telegram that the U.S. send at least “5-10 participants in literature” to ensure that the “minimal expectations” of the Federal Military Government of Nigeria (FMG) and the International Festival Committee (IFC) were met. While there was no attendance list recorded, adding the writers mentioned shows that the U.S. delegation included at least five times this. Poet Margaret Walker’s “For My People” was set to music as the festival’s official anthem. Promotional leaflets cited it as “inspiring millions of Black Americans in their continuing struggle for survival.” Moreover, in the five-hundred page anthology of “some of the best” fiction and poetry presented at Festac, U.S. participants accounted for almost two-hundred pages.

The decision to include more literature served both as a corrective to the perceived exclusion in Dakar and as a means to lend the festival more longevity. Theo Vincent of the University of Lagos suggested, in his introduction to the aforementioned anthology, that FESTAC’s legacy depended on its literary component:

Literature by its very nature tells us more about a people, a society, a situation, an experience, in one compressed whole than any other record can. And the printed word is certainly one of the most enduring ways of preserving ideas and memories. For after all the fever and heat of festivities, after the echoes of the dying footfalls of departing celebrants, the mementoes we come to cherish are those that transcend time.

It is clear that significant stakes were attached to the nature and quality of the literature, and especially its divestment from European-derived, white aesthetics and thematics. Unsurprisingly, Festac also drew an impressive number of academics from the US to weigh in on this question. Nearly all of the chairs of the nation’s newly established Afro-American Studies programs were present. Attendees included Eileen Southern of Harvard, Darwin Turner of the University of Iowa, Houston Baker of the University of Pennsylvania, Ronald Walters of Brandeis and Howard, John Henrik Clarke of Hunter College, Lucius Outlaw, interim chair at Boston College, and George E. Kent of the University of Chicago. Their presence reflected the robust institutional presence of Black Studies and Afrodiasporic studies in the United States, which quickly increased in number from the late-1960s on. It also showed the necessity of outlining how literature and academics related in the struggle against white supremacy and how U.S. literature fit into this.

Given the sheer volume of U.S. participants, a central question was how to situate literary works produced outside of the African continent. Basil Matthews, professor of sociology and literature at Howard University, was the vice-chairman of the festival’s working group on black civilization and literature. The key question that the group set out to answer was deceivingly simple: how does one recognize a black literary work? By the end of the three-day colloquium, the group presented a new definition of Africanity that was to be a template for subsequent diasporic literary production. This literature was to be unbounded by nationality; when qualifying as African literature, it was not national origin, language, or publication venue that mattered. It was a more abstract “sensibility.” As the report held:

Africanity is the affirmation of the personality, the identity, and the richness of the African way of life in the world literary field. It shows to the world the cultural traits that are common to African peoples; it has domesticated foreign languages and charged them with the specific sensitivity of Africans all through the works of African writers. African artists speak to man and to humanity through a language, images, themes, and techniques that belong to Africa. African literature thus has crossed the frontiers of the African universe to become interested in man’s condition in general.

Articulations like this one influenced Marshall in her writing of Praisesong for the Widow, a novel that oscillates between an explicit interrogation of the black elite’s role in racial advancement—or rather, their alienation from quotidian struggles—and subterranean veneration of the role of bourgeois racial representatives.

Festac’s legacy thus remained palpable, even if at the time it remained relatively uncovered by U.S. media and only received some renewed attention when the story of Holte and his collection popped up. Nevertheless, African American literature received an enormous boost by its representation at Festac. Holte’s library gave it material footing on the continent, and authors such as Marshall were invited back time and again by African governments to come speak on their work. Indeed, Festac may have faded from memory in the U.S, but the recovery of its legacy is crucial to understanding the status of Afrodiasporic literature of the late twentieth century in its worldly emanations.

Suzanne Enzerink is a PhD candidate in American Studies at Brown University. Her dissertation focuses on racial triangulation and racial ambiguity in transnational visual and literary productions of the Cold War. Her writing has appeared in American Quarterly and The Rumpus. Follow her on Twitter @suzanneenzerink.