Towards an Antifascist Pedagogy

On February 19th, 2019 an interracial group of socialists gathered at a local coffee shop in rural Alabama. The coffee shop, affectionately known as Moma Mocha’s, is a bustling café located just steps away from the campus of Auburn University. The mom and pop business pays its workers well, offers full benefits, and supports Black workers who choose to rock Black Lives Matter regalia during work hours. In short, the space is well-known as an oasis for people of color, the LGBTQ community, and radical political organizations.

That night, the East Alabama Socialist Party had organized a reading group. The text was Robin D.G. Kelly’s Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression. The Black barista was proudly wearing his yellow-lettered Black Lives Matter button. Everything appeared as it should. This was the Alabama for which I signed up. The real Southern rebels hiding just beneath the surface—slowly building power to break through the current political horizon.

As students studied for midterms and committed socialists explored their proud history as a vanguard force in the state’s Civil Rights Movement, one white Southerner—blind to this long tradition—decided he’d had enough. Zachary Tyler Hay, stormed out of the coffee shop, went to his car, and strapped a loaded gun to his waist. He stormed back in, jumped on a chair, and went on a racist tirade that included the phrases “white power,” “white lives matter,” and “Heil Hitler.” After flashing a Nazi salute to the diverse group of café patrons and gesturing towards his gun in a threatening manner, someone thought it was best to call the cops.

True to form, however, the local police department defended the fascist. Their rationale? The American Constitution. According to officers on the scene, Nazis have a First Amendment right in cases like this to “free speech.” These agents of state power further reasoned that this particular Nazi was openly carrying in an “open carry” jurisdiction—Alabama. The Second Amendment, since its inception, granted all angry fascists the right bear arms. The fact that this individual fascist was disturbing the peace and engaged in disorderly conduct did not matter. The fact that he was trespassing on the sacred soil of private property did not matter. The fact that he issued multiple terrorist threats also did not matter. He was an armed white man in Alabama. Any crime short of actual physical violence, in this case, was not going to attract state violence but, rather, state protection.

Unfortunately, this should come as no surprise. Even outside of Alabama, most police officers are statistically at least somewhat sympathetic to far Right politics. According to a recent Pew Research report, 92% of police officers nationwide believe Black Lives Matter is rooted in “long-standing bias against the police” while only 6% of white police officers believe that America needs to “continue making changes to give blacks equal rights with whites.” Given this wider context, not only would this fascist not be arrested for the multitude of crimes he committed that night, but, as the police walked him out to the parking lot, they openly discussed future tactics with him. According to an eyewitness, one of the police officers asked the fascist politely to just be more low-key with his fascism next time, telling him “Don’t do that in public, man. It scares people.”

At 9am the next morning, I was supposed to give a lecture to my world history course. At 8:59am I still had no idea what I was going to do. A week earlier, an Alabama newspaper editor had called on “the Ku Klux Klan to ride again” and “get the hemp ropes out” to lynch “socialist-communists.” Had last night’s Nazi taken note? A week before that, a student at Auburn High School posted a Snapchat picture of herself in blackface with the caption “Is this what being a n***** feels like?” Were her parents the cops on the scene? I just couldn’t do it. I cancelled my lecture.

But I couldn’t leave my students alone. I couldn’t let the fascists win. I also couldn’t normalize these events by just moving on with business as usual.

Instead, the students and I agreed to a voluntary teach-in where students could read about what happened, explore their feelings, discuss possible responses, and contextualize the event historically. My first concern was with their safety and mental health. Had any of my students been there? One had. Did anyone know who this Nazi was? No one did. Was he a student at Auburn? Thankfully not (I checked the directory). Before we started, I assured anyone who would rather not participate that the TA’s were not taking attendance and I would respect them if they didn’t want to live with this topic for an hour. One of my Black students walked out. Confronting fascism and creating an anti-fascist classroom is not for everyone. I’m not sure it’s for me. My initial impulse was to walk out with him.

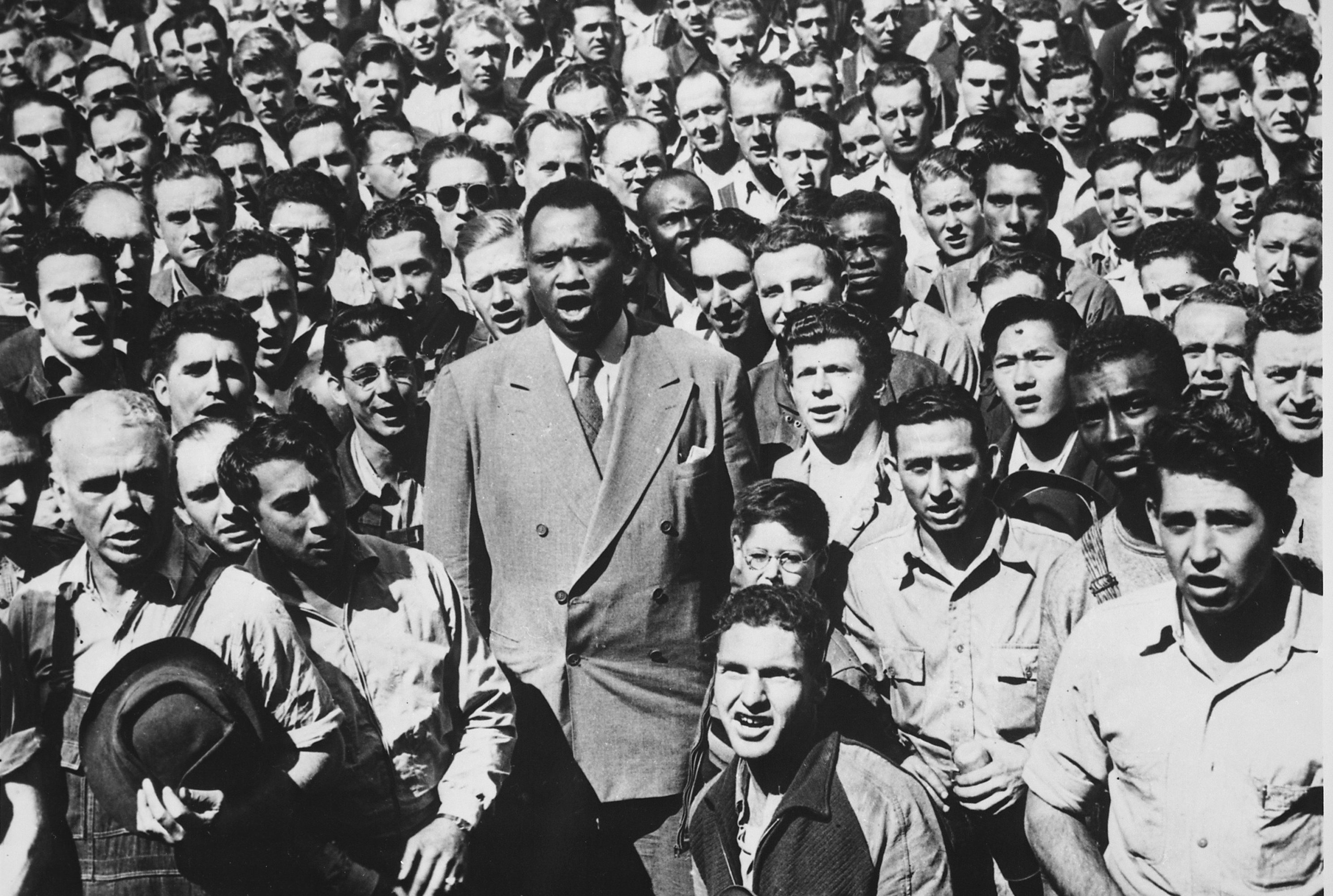

Fortunately, a long history of Black radical tradition provides ample material to draw upon in building an anti-fascist pedagogy. During the Spanish Civil War, Paul Robeson interrupted his vacation in Moscow to participate in an anti-fascist rally at London’s Royal Albert Hall in 1937. The event was a rapid response to the bombing of the largely anarchist/socialist/communist Basque town of Guernica by Italian fascists and German Nazis (an event famously portrayed by Pablo Picaso). Over a thousand civilians were killed.

As fascism struck, Robeson struck back. He cleverly circumvented Nazi censorship technology by broadcasting a fiery speech from Moscow directly to the gathering in London. In it, he declared that “[t]here are no impartial observers” in the fight against fascism. Robeson assured his listeners that “the battlefront is everywhere.” He knew that fascism might best be conceptualized as capitalism with its fangs out. Foreshadowing (or perhaps in conversation with) the soon-to-be published Williams thesis, Robeson proclaimed that “[t]he history of the capitalist era is characterized by the degradation of my people.” In further connecting the anti-slavery struggle to the anti-capitalist/anti-fascist struggle, Robeson framed his stance towards fascism as a choice where everyday people “must elect to fight for freedom or slavery.” For Robeson the choice was clear—an anti-fascist society must “be defended to the death.”

Building on Robeson, Angela Davis extended this Black anti-fascism to her analysis of the prison industrial complex. Davis, writing from inside Marin County Jail in 1971, saw everyday policing as a form of proto-fascism being used to suppress the lumpenproletariat of Black and brown people during a moment of emerging political consciousness. As Davis pointed out, incarcerated peoples like her were well aware of this connection. The Folsom Prisoner’s Manifesto, she noted, made clear that men inside Folsom believed they were living in the “fascist concentration camps of modern America.” Learning from Robeson’s era, Davis claimed “[o]ne of the fundamental historical lessons to be learned from past failures to prevent the rise of fascism is the decisive…fight against fascism in its incipient phases.” If an armed Nazi rant in an Alabama coffee shop is an “incipient phase” then Davis would demand an antifascist pedagogy that is part of “an indivisible mass movement which refuses to conduct business as usual.”

Following Davis and Robeson, the first rule of an anti-fascist pedagogy then is to refuse to continue with “business as usual” and recognize that the anti-fascist battleground is everywhere. While I’ve previously thought a lot about how to decolonize the classroom and foster a diverse, horizontal, inclusive learning environment, incorporating an anti-fascist pedagogy demands something more. While I will continue to teach my #AuburnWorldHistory course from a Black Atlantic perspective, I’ve started paying much more attention to the places where fascism and its tendencies pop up. While I often posit ethical dilemmas to my students, I’ve turned more sharply towards questions such as: “What would Jesus say about fascism?” And “how do we draw the line between patriotism, nationalism, and fascism?” “What would you do if you were in NYC in 1939 and Nazis wanted to hold a mass rally at Madison Square Garden?’” For my overwhelmingly white conservative students at Auburn, I now see my job as asking them these questions before the fascists do. I also spend a lot more time exploring how to identify propaganda and logical fallacies. In this way, my job has become simple: I’m counter-recruiting—interrupting the manifold efforts of fascists to radicalize my students. If one of my white students ends up as the next coffee shop Nazi, I will have failed as a professor. Success, on the other hand, is something I now measure through my handful of African American (and other marginalized) students, rarely at risk of becoming fascists themselves. If they know unquestionably that I love them and will defend them “to the death” then my anti-fascist pedagogy was a success. As Alabama politicians attempt to make the state (and indeed the nation) look like an episode of The Handmaiden’s Tale, building an anti-fascist pedagogy can’t wait another summer. Share your ideas at #AntiFascistPedegogy.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.