“To Be Proud of Being Who We Are”: Remembering Leslie Brown

At the end of our lives, if we are lucky, most of us can only hope to be proud of being who we are. The historian Leslie Brown, who recently passed away, understood this concept more than most. Throughout her life, Brown came to embrace every part of herself—her identity shaped by the experiences and people from childhood to her intellectual journey in academia. History confirmed who she knew she was. “I was born a historian,” Brown wrote in her autobiographical essay, “practiced in the art of interrogation.”1

At the end of our lives, if we are lucky, most of us can only hope to be proud of being who we are. The historian Leslie Brown, who recently passed away, understood this concept more than most. Throughout her life, Brown came to embrace every part of herself—her identity shaped by the experiences and people from childhood to her intellectual journey in academia. History confirmed who she knew she was. “I was born a historian,” Brown wrote in her autobiographical essay, “practiced in the art of interrogation.”1

In her scholarship, she well knew and made it abundantly clear that the study of history could be an extremely personal undertaking. In other words, the historical is personal and there is a lot we can learn about ourselves through the lives of others because history is transformative in that way.

I first met Leslie Brown through her work, then in person in April 2009 after attending one of her lectures at the historic St. Joseph’s AME Church in Durham, North Carolina, an institution she vividly brought to life in her study of black Durham. In the few conversations I had with her, she inspired and encouraged my own research on the Bull City, which has the benefit of using oral histories from “The Behind the Veil Project” that Brown worked on while at Duke University.

I once wrote in a book review of Upbuilding Black Durham: Gender, Class, and Black Community Development in the Jim Crow South that “Brown’s powerful writing and careful research come alive in the many voices she uses in tracing the development of Durham’s black community from emancipation to the early 1940s.”2 The book won the Frederick Jackson Turner Award from the Organization of American Historians in 2009. If I can write a first book half as good as Upbuilding (one of my historical “bibles”), I will have done my job as a historian. Here, Brown gave us a rich and lucid piece of historical scholarship because she appreciated and perfected the art of storytelling. As a brilliant storyteller, she made her work accessible to everyone.

I once wrote in a book review of Upbuilding Black Durham: Gender, Class, and Black Community Development in the Jim Crow South that “Brown’s powerful writing and careful research come alive in the many voices she uses in tracing the development of Durham’s black community from emancipation to the early 1940s.”2 The book won the Frederick Jackson Turner Award from the Organization of American Historians in 2009. If I can write a first book half as good as Upbuilding (one of my historical “bibles”), I will have done my job as a historian. Here, Brown gave us a rich and lucid piece of historical scholarship because she appreciated and perfected the art of storytelling. As a brilliant storyteller, she made her work accessible to everyone.

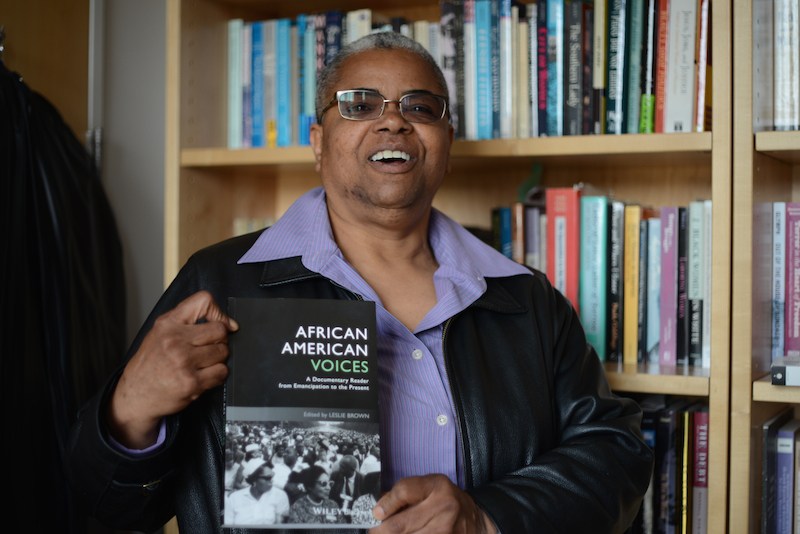

Brown brought the people we’ve always known in our own lives—especially black women—to the forefront by giving them their just due. In Upbuilding, we not only learn intricate details about the life of Pauli Murray (the “black activist, feminist, lawyer, priest, and poet”), but her grandmother Cornelia Fitzgerald and teacher aunts Pauline and Sallie Fitzgerald.3 We are left with a long-lasting connection to her subjects because she made a point to tell us the names of those tobacco workers, domestics, teachers, nurses, and secretaries who became activists in their own right and served as the “core labor force” in black communities across the South. In this way, she challenged classic narratives that placed black men at the center and complicated our understanding of how black women confronted racism, perpetuated by Jim Crow, in vastly different ways than their male counterparts. Brown followed up her first book with Living with Jim Crow: African American Women and Memories of the Segregated South, and African American Voices: A Documentary Reader from Emancipation to the Present.

By all accounts, Brown held a deep commitment to undergraduate teaching, research, and mentoring. I was pleased to learn about the publication of African American Voices, which is one of the main reasons I now have my undergraduate students produce their own individual chapters to be included in a course documentary reader. One is struck by the level of involvement in this work by her students, which demonstrates her willingness to engage history from multiple perspectives.

Brown leaves an enduring legacy—indeed a historical footprint—through the permanence of her scholarship. The path she blazed, made possible by the black women historians before her, will continue to shape the historical profession for decades to come. We can all be proud of who Leslie Brown was and thankful that she made it one of her assignments to ensure there was a space for all.

Brandon K. Winford is an assistant professor of history at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. He’s completing his first book manuscript, Building New South Prosperity: John Hervey Wheeler, Black Banking, and the Economic Struggle for Civil Rights. Follow him on Twitter @Winhistory24

- Leslie Brown, “How A Hundred Years of History Tracked Me Down,” in Deborah Gray White, ed., Telling Histories: Black Women Historians in the Ivory Tower (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 268. ↩

- Brandon Winford, Book Review of Upbuilding Black Durham: Gender, Class, and Black Community Development in the Jim Crow South, North Carolina Historical Review 87 (April 2010), 225-226. ↩

- Pauli Murray, Pauli Murray: The Autobiography of a Black Activist, Feminist, Lawyer, Priest, and Poet (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1989). ↩

Thank you Dr. Winford for this piece on the late Dr. Leslie Brown. There does seem to be a vacuum of sorts when it comes to the many, many voices of African American women who were engaged and still very much engaged in the struggle that effects all people of color. These are voices that have been held captive by the silence that has been imposed upon them in one way or another. I discovered that truth during my first semester in grad school writing about Ella Baker, Diane Nash, and Fannie Lou Hamer (whose voice we have heard). Dr. Brown has left a legacy and there are some in the Academy who are bringing more of the voices of our sisters to bear on the public’s consciousness. Hopefully there will be many more. May Dr. Leslie Brown rest in eternal peace, and may the baton be picked-up by others to complete the work that she started.

Dr. Talley, thank you for your comments and for reading the reflection. I agree with everything you said.