The Women at the Heart of Black Power

*This post is part of our online roundtable on Ashley Farmer’s Remaking Black Power

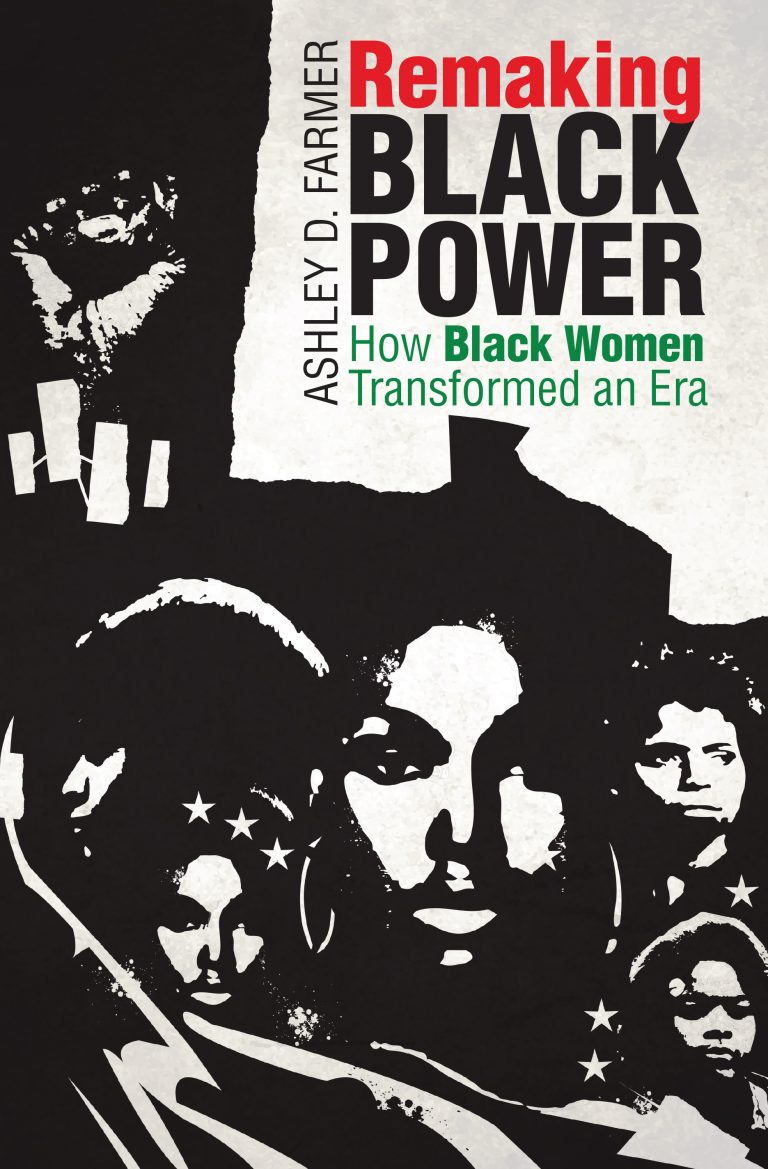

Ashley D. Farmer’s Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era is a compelling, groundbreaking work that intervenes in an impressive array of historical subfields. First and foremost, Farmer’s book represents a significant corrective to interpretations of the Black Power movement that have excluded women from the movement’s history. This alone marks a substantial contribution to our understanding of the Black freedom struggle and African American history more generally. Farmer demolishes the widespread but mistaken notion that women operated on the margins of Black nationalism, struggling to have their voices heard in organizations controlled by men. Despite scholarship on women in Black nationalist movements by Robyn Spencer, Bettye Collier-Thomas, V.P. Franklin, Keisha N. Blain, Ula Taylor, Donna Jean Murch, Mary Phillips, and Angela LeBlanc-Ernest, this fallacy endures not only in the popular imagination but also in some quarters of the historical profession. Farmer, however, persuasively argues that women demanded to be at the center of the movement. In her words women Black Power activists developed “competing models of black womanhood . . . to advance Black Power tenants and assert the primacy of women in political organizing” (5). Rejecting the sexist notion that they were merely assistants or accessories to male leaders and public speakers in the movement, Black Power women fought to be treated by their male comrades as equal soldiers in the struggle.

Remaking Black Power is a consequential work of intellectual history. Farmer analyzes women not as ancillary to a Black Power movement dominated by men, but as independent intellectual actors who developed their own visions of liberation. Most importantly, the activists in Farmer’s work labored tirelessly to establish archetypes of women that could effectively advance Black nationalism. “Using their new models of black womanhood,” Farmer explains, “black women activists reformulated Black Power ideas and symbols and bent the era’s major organizations toward more inclusive emancipatory visions” (5). These models of Black nationalist womanhood fill the pages of Farmer’s work: the “Militant Negro Domestic” championed by communists and radicals from the middle of the 1940s to the dawn of the Black Power era; the “Black Revolutionary Woman” hailed by the Black Panthers; the “African Women” who worked in cultural nationalist groups such as the Us Organization and the Committee for Unified Newark; and the “Pan-Africanist Women” embodied by the organizers of internationalist conferences such as the Sixth Pan-African Congress (PAC); and the “Third World Black Woman” that emerged from groups such as the Third World Women’s Alliance. The book is very much a history of dueling images and imaginations.

Remaking Black Power is, of course, a history of feminism. In the last decade, historians such as Winifred Breines and Kimberly Springer have published books on the history of Black women in the feminist movement, and Sherie Randolph, Rosalind Rosenberg, Kristen Hogan, and Keeanga Yamahtta-Taylor have significantly expanded that literature in just the last three years. But the history of Black women in the feminist movement still has not garnered nearly as much attention as it deserves. This is especially true for the history of Black feminists operating in Black organizations (as opposed to works on Black feminists who worked within majority-white organizations). Remaking Black Power offers readers a transformative analysis of the little-understood and little-known history of Black feminists in the Black Power movement. Even if many of the women in Remaking Black Power may not have explicitly self-identified with feminism, the Black Power women’s struggle for gender equality was a feminist undertaking. As Farmer argues women in the Black Power movement “implicitly [and] simultaneously identified as nationalists, socialists, and feminists as a way to expand their ideological and activist range” (188).

Thus at its core, Remaking Black Power operates as a history of intersectionality. Readers will likely know that the legal scholar Kimberle Crenshaw coined the term in 1989, or that activists like the Combahee River Collective employed an intersectional analysis in their writings in the second half of the 1970s. But some readers may be surprised to learn that intersectional analysis was at the heart of Black nationalist women’s ideology at least as early as Louise Thompson Patterson’s writings on the “triple exploitation” of the “Bronx Slave Market” in her 1936 essay, “Toward A Brighter Dawn” (27). Indeed, one of Remaking Black Power’s great insights is identifying this thread of intersectionality that connects Black nationalist women from the 1930s to the late-1970s. Thus, Black nationalist women enthusiastically practiced intersectionality long before Crenshaw coined the term.

Farmer skillfully maps out the contours of Black nationalist women’s intellectual work in this concise volume. Farmer has performed a considerable service both for historians and for lay readers by condensing the history of Black nationalist women from World War II to the late- 1970s into a slim two-hundred-page manuscript, plus endnotes. A book of this brevity is short enough to teach in undergraduate classrooms and more likely to attract general readers than a more extended work. Indeed, we need more texts like this in the history of Black Power that are accessible to non-specialists.

But no single work could comprehensively address the many nuances and complexities of Black nationalist women’s history. Several avenues for future scholarship on women in the Black Power movement come to mind. First, how did women in the Black Arts movement shape broader understandings of women’s roles in Black nationalism? In asking this question, I am employing James Smethurst’s dual definitions of Black Arts as the “cultural wing of the Black Power movement” and Black Power as the “political wing of the Black Arts movement.” Women of the Black Arts movement such as Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, Jayne Cortez, and Ntozake Shange produced widely received and profoundly influential portrayals of Black women in the 1960s and 1970s. We know these artists had a significant impact on the Black Power movement, but what was that impact? Did the activists in Remaking Black Power think of Black Arts women as doing the same political work, or did they see it differently?

Second, what did feminists outside Black Power—both Black and white—think of Black nationalist women? Many white feminists misunderstood and misconstrued the political work of women in the Black Power movement, and some were even wholly ignorant of it. But did some non-nationalist feminists recognize the work of Black Power women? If so, who were they?

One can ask the same question of Black nationalist men—how did they respond to the demands of their sisters in the struggle? Farmer indeed explores this question, but there is still room for other scholars to investigate how Black Power men resisted or accepted the demands of women in their movement. An intriguing and not entirely unproblematic example of this dynamic is in the case of the Us Organization. One of the many insights Remaking Black Power reveals is that the Us Organization transitioned from mandating polygamy and demanding women adopt a “subjugated or submissive role within the family” (99) in the late 1960s to Maulana Karenga rejecting “sexist interpretations of cultural nationalism” by the mid-1970s (122). Karenga’s shift is a remarkable transformation, one that was likely the result of urgent and contentious debates, and it would be valuable to know more about how women in Us (and other Black Power groups) pushed and persuaded men to change their deeply patriarchal attitudes.

Another pressing question is how Black nationalist women understood reproductive rights and sexual assault. Farmer discusses how these issues proved thorny for many in the movement other than the Third World Black Women’s organizations, which embraced reproductive rights. But some Black nationalists went as far as to condemn birth control and abortion as “tools used in a state-sponsored genocide of black Americans” (183). A historian could devote an entire article, if not a whole book, to how Black Power women addressed reproductive rights or sexual abuse.

Finally, Farmer illuminates a tremendous amount about how Black nationalist women thought about their place in the broader world and especially their relationship to Africa and Africans. A fascinating topic for historians to address further would be the question of what the world outside the United States thought about Black Power women. Most importantly, what did Africans make of women in the movement? And what about nations and political actors who associated themselves with anti-imperialism and national liberation—what did they make of Black Power women? The scholar Sophie Lorenz, for instance, has explored how East Germany embraced Angela Davis and elevated her to the level of national hero.

By uncovering a wealth of new insights on Black Power women and provoking additional questions for future research, Farmer achieves precisely what she sets out to do and persuades readers to fundamentally reconceive their understanding of the role women played in Black nationalism. We can only hope that other scholars will build on Farmer’s signal work and answer her call to investigate Black women’s essential contributions to the Black Power movement.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.