The Transformation of Black Politics in the Liberator Magazine

This post is part of our online roundtable on Chris Tinson’s Radical Intellect

Christopher Tinson’s Radical Intellect: Liberator Magazine and Black Activism in the 1960s is a work of assiduous archival research about a magazine long known to be a venue for Black radical thinkers. In five chapters, Tinson covers the magazine’s 10- year run, touching on its contributions to debates about the relationship between African and Black American liberation, women’s rights, Black aesthetics, and the centrality of culture to Black revolution. Liberator writers were a “who’s who” of Black thinkers including James Baldwin, Sonia Sanchez, Harold Cruse, Larry Neal, Amira Baraka, Lorraine Hansberry, and Askia Touré. By mining the Liberator’s archives, Tinson seeks to describe the political battles, critical ideas, and charismatic leaders that formed the backbone of Black internationalist politics and the Black radical tradition in the 1960s and early 1970s. Moving us beyond the stale civil rights versus Black nationalism, Old Left versus New Left debates that defined 1990s academic discourse, Radical Intellect joins recent scholarship that has expanded our sense of this pivotal era in world history.

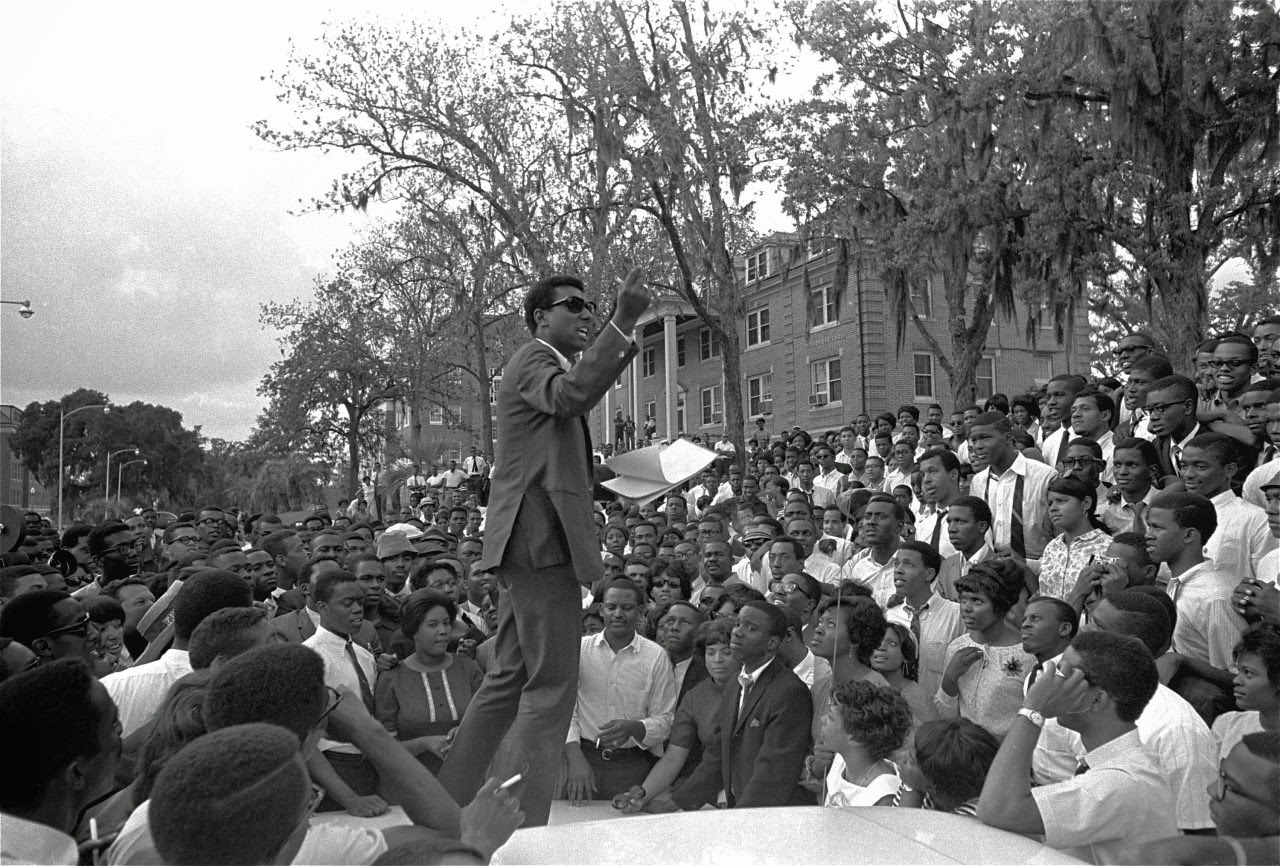

The Liberator began in 1960 as the 5-page newsletter for the Liberation Committee on Africa (LCA). The magazine was founded by Editor-in-Chief Dan Watts, a disenchanted architect, who, like so many of his generation, became captivated by African independence movements and the charismatic leaders who symbolized them. When Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba was assassinated by Katangan separatists backed by the CIA, Watts, Pete Beveridge, and Richard Gibson, formerly of The Fair Play for Cuba Committee, established the LCA. Its mission was to explore the role of the U.S. in thwarting anticolonial efforts, an effort that emerged, they felt, from some of the same impulses that prevented Black American liberation. The Liberator was a platform for analyzing global white supremacy and how African and Black American communities might overturn it. A forum for considerable ideological diversity, Liberator’s contributors discussed the role of Pan-Africanism, anti-imperialism, Communism, socialism, cultural revolution, aesthetic innovation, and Black women’s liberation in forging diasporic and continental ties free of Western interference and defined by authentic national and racial equality. In the magazine’s evolution, we see the decade’s evolution: from the exuberance of African independence in 1960 to the despair felt by mid-decade as military coups squashed democratic hopes; from the focus on a singular Black American community to a recognition that gender and sexuality forge multiple Black communities that experience white supremacy differently; from a focus on Black national or community independence to a more circumscribed belief in Black cultural autonomy. The Liberator captured these shifts because many of its contributors helped make them happen.

Radical Intellect succeeds on its own terms. It is a comprehensive analysis of Liberator magazine, covering how it was formed and why, how the decade’s various developments found expression in the magazine’s pages, and which contributors most influenced the magazine and the larger cultural moment. We discover that Harold Cruse’s Liberator essays eventually served as the backbone to his two seminal volumes The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual and Rebellion or Revolution?, inspiring younger writers like Askia Toure and Larry Neal to foster a Black Arts Movement. We learn that a special issue on Black women featured debates on the relationship of anti-imperialism and communism to gender inequality, debunked the infamous Moynihan Report, and argued that reproductive choice and ending police brutality were both critical Black women’s issues. As with Cruse’s work, many of those ideas found their way into Liberator contributor Toni Cade Bambara’s anthology The Black Woman (1970), a seminal work of Black radical and feminist thought. Both are compelling examples of how Liberator magazine was an “incubator” for the development of Black radical ideas on a wide range of issues from Black theater to birth control.

What is missing, however, is a sense of how the magazine’s ideas were shaped by the personal and political experiences of those who wrote for it. Radical Intellect includes plenty of detail about the magazine’s contents: who wrote what and when. But we learn little about how ideas and opinions emerged from both solitary thought and engagement with the world. What was the texture of the connection between Liberator writers and local struggles? How involved were they and in what ways? What was the connective tissue, the bone and blood that linked people to organizations, ideas to actions? How did individual and collective experiences shape who wrote and what they could and did say? Tinson shows us how writers responded to one another, but what were the other conditions of production in which these reviews, articles, and essays were written? Without this, Radical Intellect feels bloodless, scrubbed of the messy, contradictory and coincidental episodes and contexts that forge ideas and Black art. Ideas clash and intersect as if independent of their producers and their social worlds. Liberator contributors and their ideas become cardboard cutouts; we see the house but not the blueprint. We are detached observers, never interlocutors or collaborators. Thus, it is hard to assess the validity of Tinson’s contention that the Liberator and other magazines “closed the distance between cities and movements for many in and around black radical artistic and political circle,” much less whether “these sites served as strategic organizing tools that linked translocal networks of activists and potential organizers” (211). To be fair, this is not necessarily Tinson’s failure but rather the failure of an intellectual and cultural history that prioritizes the product (the essay, poem, play, novel, music, etc.) over of the process, stripping away the contexts and interrelations that make the product possible.

This oversight has critical, often gendered and classed political consequences. It obscures the very privileges that make creative and intellectual work easier for some and harder for others and fails to show how those privileges impact what is produced. How did the fact that Black Arts icon Amiri Baraka was a heterosexual, cisgender man with an ex-wife and a wife raising his young children shape his creative output? Conversely, how did childrearing, misogyny, low-wage work, healthcare disparities, and homophobia impact that of his contemporary Audre Lorde? Documenting the relationship between cultural work and its deep conditions of production might shift how we define intellectual and cultural work: where it happens, who does it, and what it looks like. It might help obliterate the image of the lone, male creator that still dominates our scholarly and cultural imaginary. It might also challenge the view of intellectual work as finite, something that can be easily distilled, read, heard, or seen at a given moment in time.

If such a shift has important consequences for who we imagine to be a thinker and creator, it might also expand where we imagine thought and culture is produced. Tinson, himself, raises this point late in the book when he concludes that compared to the 1960s and 1970s, “African American and Afro-diasporic cultural and political thought in the public domain has deteriorated” (241). The Liberator and other publications were “black studies departments before American universities and colleges were forced to embrace the Black Studies and Ethnic Studies movements. They were training grounds for numerous cohorts of activists, groups, and individuals. They were sites of strategy and planning. They were spaces of critical interrogation of governmental policies that anticipated the CNN network’s all-day political punditry and the age of contemporary public intellectualism” (241). If this is true, and I believe it is, what has the institutionalization of Black studies meant for these endeavors, and what is the relationship between institutionalization and a shrinking public domain? As the head of an African American studies department at a Research 1 institution and a veteran of other administrative positions at both public and private, small and large universities, I can say that efforts to link students of color and community members, pedagogy and political organizing, knowledge production and radical social change are rarely rewarded. In fact, they are discouraged and often punished. Of course, some Black studies work can and does create and expand the space in which such projects exist, but context, relationships, privilege, and inequality matter in today’s academy no less than they did in the Black literary exchanges of the 1960s.

If one sees the Liberator and Black studies as the primary sites of Black radical interrogation, strategy, and planning, then we overlook the fact that grassroots organizing and a daily politics of refusal are and have been every bit as critical to the formation of the Black radical intellectual tradition. We might conclude, as Tinson does, that the cooptation of Black radical thought into colleges and universities means that the Black public domain is impoverished. But if we expand our view of intellectual and cultural work both inside the academy and outside of it, we might appreciate its myriad forms. In our contemporary moment, we might better appreciate how mass incarceration and the murder of unarmed Black people by police and armed civilians has produced multiple intellectual responses: grassroots political mobilization, social media conversation, daily dissent, as well as cell phone recordings, podcasts, film documentaries, think pieces, investigative reporting, college courses, and yes, academic tomes. Scholars readily recognize the radical intellectual work involved in the Movement for Black Lives’ Vision for Black Lives: Policy Demands for Black Power, Freedom and Justice.

Are we, however, as critically engaged with more ephemeral articulations like the #livingwhileblack twitter campaigns that shame white people who dial 911 on Black people simply for napping, barbecuing, sitting, or standing in public spaces? Can we appreciate the daily forms of refusal enacted at the moment that ordinary Black life resists white surveillance and domination as significant intellectual and cultural interventions that challenge dominant ontological and epistemological assumptions? Or is it only when these forms are recorded and circulated or when they galvanize mass protest or local organizing that they matter? Or, to take another example from a recent lecture Joy James delivered at The Ethics of Policing conference, are the mothers, grandmothers, and girlfriends who take in their formerly incarcerated loved ones enacting a transformative political activism that cannot be easily coopted or incorporated into the current social arrangement?

I would add: Are they reframing Black criminality and Black nurturing as central, each in its own way, to a transformative politics, a reframing that constitutes significant, if unrecognized intellectual and cultural work? I am not claiming to have sufficient answers to these questions, but I want to write and read cultural and intellectual history that grapples with them. I am not interested in rehashing stale debates about whether such acts are radical or reactionary, rebellious or revolutionary. Instead, I want to think about how small moments, everyday acts, and ephemeral objects, whether on Twitter or in one’s local coffee shop, might be, as anthropologist Claude Lévi Strauss once wrote, “good to think with,” which is part of a structure of thinking that might finally get Black people free.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.