The Smile Beyond the Mind: Minkah Makalani Reflects on Cedric Robinson

Today we continue to honor the life and legacy of Professor Cedric Robinson who passed away earlier this week. Dr. Robinson was a beloved scholar and mentor who authored several foundational texts including Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition and Terms of Order: Political Science and the Myth of Leadership and Black Movements in America. We began with reflections from Professors David J. Leonard and Josh Myers. In today’s post, Dr. Minkah Makalani reflects on Dr. Robinson’s kindness and generosity.

***

Over the past few years we have witnessed the transition of a number of our intellectual giants. Each loss brings with it a sense of unmooring, as if we have lost not only someone whose work inspired us in some way, but someone who worked tirelessly either to anchor us in this world, or to help build another world where we might finally sink our soul into the soil. Our melancholia is in part a realization that no one else will ever offer the insights, sensibilities, and brilliance of those on whom we bestow that hallowed honorific, ancestor.

Their works will remain, however, and if we are to truly honor them, we will continue to explore, expand, and critique their ideas, for they never saw themselves offering sacred texts. We honor neither gods nor heroes, neither saints nor sinners, but people who were, like those left to mourn them, frail human beings who captured something of their own and our imaginations with their words, music, and movements, which helps us approach the unknown. And beyond the profundity of any of their ideas, often we revere them because we have been touched by their generosity, the feeling that they saw something in us that, while healing, remained exposed. Maybe it was a small gesture, a habit cultivated over time, which allowed them to display their intellects in such a way as to seem more an invitation into a conversation than a final statement.

The transition of Cedric Robinson has certainly struck a number of us in academia deeply. Like so many, I encountered Robinson initially in his work, when I first began to study seriously C. L. R. James and Oliver Cromwell Cox, an endeavor for which his articles, “Oliver Cromwell Cox and the Historiography of the West,” and “C. L. R. James and the World-System,” provided an intellectual roadmap. It would be nearly 20 years, however, before I would meet him in person.

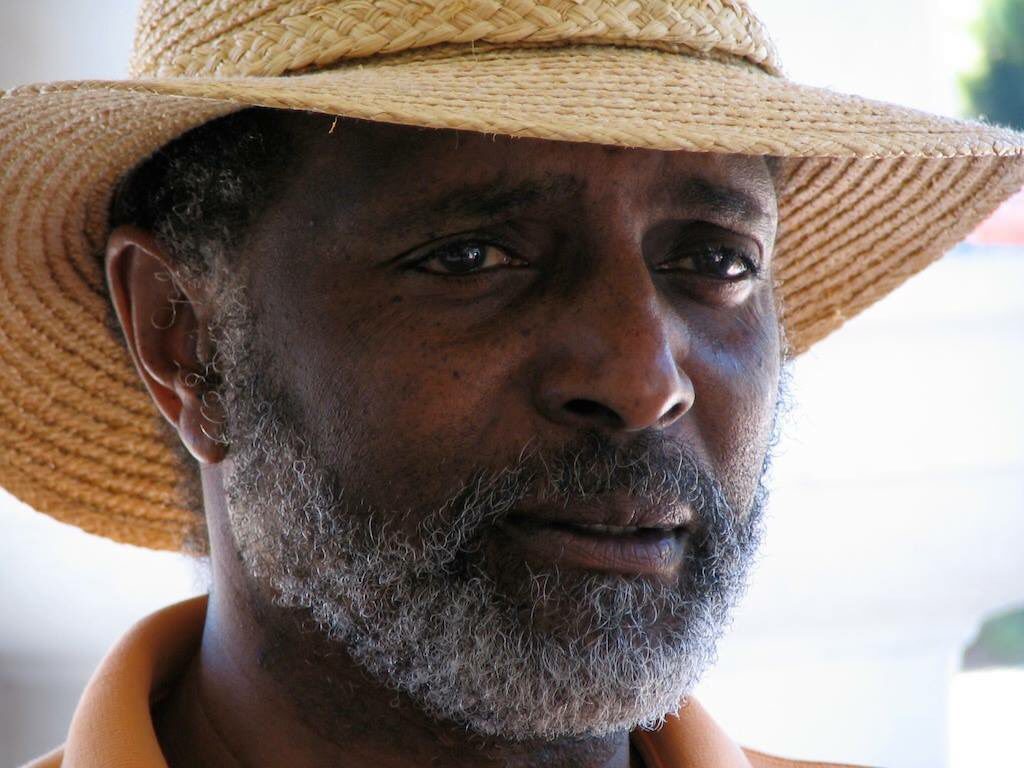

When I first saw Cedric Robinson, he was in the hotel café at the 2010 American Studies conference in San Antonio, TX. He was shorter than I had imagined, and wore what I now recognize as his signature wide-brimmed hat. It was late, so I choose to say nothing, certain he had no interest in meeting yet another person telling him how his work had changed their whole approach to scholarship. To have said this, though, might have been disingenuous. Over two decades, I had read and reread his classic work, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, and found myself disagreeing with it in important ways, though there was no missing its analytical weight and theoretical importance. I saw myself taking him seriously enough to explain why and where I disagreed. But this is academia, where folks are known to have membraneously thin skin. And I was still reeling from having been denied tenure just two months earlier, so I left him alone.

When I saw Dr. Robinson the next afternoon, waiting for friends after a panel, I steeled my nerves and introduced myself. To my surprise, he knew my work, which gave me the odd sensation of dread. My book was not yet out, so how did he know my work? Then it dawned on me, and in those few seconds, which seemed to slow down and stretch into hours, I realized that he had written for my tenure file! Cedric Robinson had read my manuscript! A manuscript had criticized him in the introduction. Certainly, I told myself, he wrote a negative letter. Except, his smile was warm, not vindictive, and he was exceedingly kind, talking with me like I imagine he would a colleague. He introduced me to several of his friends and graduate students, and when he heard of my tenure denial, he assured me that whatever mistake had been made would certainly be corrected.

In a profession that daily chips away at your self-esteem, fosters self-doubt far more than confidence, and praises far more easily your ability to read and assimilate the latest intellectual fashion than your ability to think independently, Cedric Robinson is a rare person. His intellect and encyclopedic recall were legendary; his pen offered the most critical of cuts; and his intellectual and personal generosity, by all accounts, was boundless.

In that weekend, with that simple encounter, Cedric Robinson restored something of my self-confidence, conveyed to me that I had, in fact, written something worth reading, and encouraged me to be in touch about my new project. To have friends encourage you is essential, and I doubt I would have recovered from that blow without them. But in that low period, I could not shake the feeling that, as friends, they were trying to help salvage my sanity. Cedric Robinson did not know me personally, and given the legendary pettiness of academia, I would not have been surprised had he ripped through my book right there, laughed while telling his friends I was the fool who tried to critique him, and for good measure, told a couple of jokes about my mother. At that moment, I would have considered such a response measured. Instead, I left San Antonio with a belief that I was doing something right, even if I were in neither the right department nor discipline.

I corresponded with Robinson only occasionally over the next few years, and saw him once more at the Critical Ethnic Studies Conference in Chicago. His smile was just as big, hat brim just as wide, and the conversation as warm as I remembered from before. He congratulated me on my current position, and invited me to dinner with his group. I had plans to meet friends, so declined. I never had the opportunity to break bread with Dr. Robinson, to engage a mind whose brilliance I had witnessed in print, to raise a glass to whatever they may have been celebrating that night. But years from now, when I no longer recall the finer points of Black Marxism, when I am unsure exactly what his insights were regarding Cox or James, I will recall vividly his smile, warm laughter, and that, like a few others in the academy, his kindness and support helped pull me up from the lowest point in my career.

Thank you, Cedric Robinson.

Minkah Makalani is an Associate Professor in the Department of African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas. His interests include intellectual history, black political thought, racial identity, black radicalism, and diaspora in the Caribbean, US, and Europe. Makalani is the author of In the Cause of Freedom: Radical Black Internationalism from Harlem to London, 1917-1939 (University of North Carolina, 2011); and co-editor (with Davarian Baldwin) of Escape from New York: The New Negro Renaissance beyond Harlem (University of Minnesota Press, 2013). In addition to editing a special issue of Social Text on “Diaspora and the Localities of Race,” his articles have appeared in the journals Souls and the Journal of African American History, and several edited collections. He is currently writing a history of C. L. R. James’s work on the West Indies Federation from 1958-1962, tentatively titled, Calypso Conquered the World: C. L. R. James and the Politically Unimaginable in the Trinidadian Postcolony. You can follow him on Twitter at @minkmak

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

What a lovely remembrance, made somehow all the more compelling because you did not know Cedric well. Yet you captured him perfectly. Thank you.