The Rise of Global Conservatism and Resistance in the Age of Trump

The travel ban on Muslims and refugees. Withdrawal of federal protections for transgender students. The reinstatement of the global gag rule on abortions. Approved and continued construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. Threats to catalyze the demise of Planned Parenthood and the construction of a wall to separate the United States from Mexico.

These racist, discriminatory, sexist and xenophobic initiatives are only a few policies Donald Trump and his administration have enacted or attempted to implement in the first 100 days of his presidency. The rise of Trump is not only disconcerting for people in the United States, but it has severe implications for racialized groups globally.

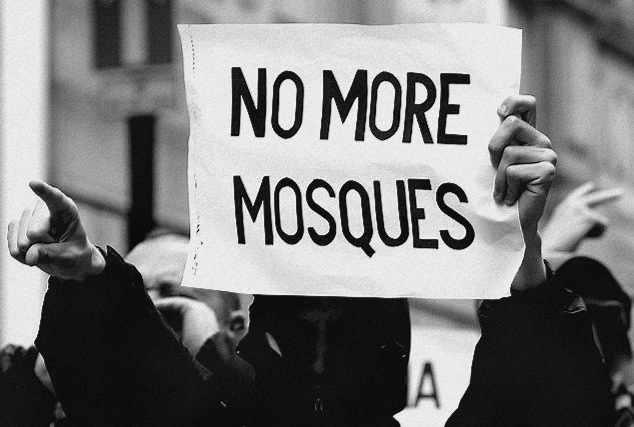

In Europe, the emergence of Trump has led to the emboldening of conservative political platforms and racist right-wing organizations that maintain a staunch anti-multiculturalist stance. Dubbed by many scholars and journalists as the second coming of authoritarian populism, examples of such European autocracy can be found in the “Brexit” referendum, which was launched by the conservative United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) as a retaliation to the influx of immigrants, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s support of a partial ban on niqabs and burkas. Merkel, at a conference for the Christian Democratic Union Party, stated “the full-face veil is not acceptable in our country.” Racist political groups such as Greece’s Golden Dawn and Russian National Patriotic Union are unifying to maintain “traditional” values in a world they view as burgeoning with too much diversity.

While racism and discriminatory xenophobic actions and policies have long prevailed in Europe, what is necessary in understanding this Western neo-fascist world order is a critical reexamination of racism and, overall, the social construction of race. Though perceptions of U.S. race relations have promoted the idea that racism is an issue only between Black and white people, this antagonism in U.S. and European contexts extends beyond mere skin color in a process known as racialization. Defined by Michael Omi and Howard Winant as the “extension of racial meaning to a previously racially unclassified relationship, social practice or group,” racialization provides a more concrete characterization of the malleability of race that extends beyond phenotype. Here, racialization in the U.S. and Europe is applicable not only to darker-skinned peoples, but to immigrants, Muslims, Romani and Sinti peoples and Indigenous communities. Many groups who at one point in history were not racialized have now become targets of exclusionary policies and are viewed as threats to Western nationalism and security.

Omi and Winant contend that racial formations can be used by social, economic and political forces to assign meaning to racial categories. Thus, these “forces” have the power to stratify, define and oppress based on various intersections including religiosity, citizenship, ethnicity, gender and the like. Although these notions can be applied throughout any point in history, now more than ever, the characteristics of racialization and racial formations could not be clearer. Trump and other European politicians and leaders are those very forces that are racializing groups to funnel their racist, white, heteronormative male-centric and white supremacist so-called Christian values as global dominion.

The widespread contemporary violence against persons of African descent, immigrants, refugees, Muslims and religious minorities in Europe is telling of how far racist politicians and neo-Nazi vigilantes will go to actualize their vision of “making Europe great again.”

A 2015 Hate Crime Report conducted by the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), which is a formal institution of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), shows the ubiquitous nature of racial and religious assaults in Europe, including violent attacks, threats and property damage. For example, the overview of incidents reported by civil society showed France’s official figures detailed 739 racist hate crimes, including 69 physical assaults, three arson attacks, 31 incidents of damage to property and 249 cases of threats. In Germany, there “were 2,447 hate crimes motivated by racism and xenophobia, with assaults on foreigners, refugees and asylum seekers.” Within recorded figures of 49,419 hate crimes in the United Kingdom—in particular, in England and Wales—“32 of those assaults reported by Muslim Engagement and Development (MEND) were physical and targeted four women and taxi drivers. The victims of those attacks were Asian, Indian, Egyptian, Algerian, Sudanese, Somali, Iranian, Turkish and Iraqi-Kurdi.”

In the article “Combatting Hate Crimes and Bias Against People of African Descent in the OSCE Region,” Mischa Thompson explores widespread incidents of racial discrimination and racially motivated attacks on persons of African descent (PAD) and Black Europeans in Europe. According to Thompson, in 2013 and 2014, the OSCE detailed 16 deaths and over hundreds of violent attacks against people of African descent. Examples of such violence can be found in Russia, Spain, Greece, Italy, Poland and Ukraine where persons of African descent have been pushed onto train tracks, assaulted with pepper spray and brass knuckles and physically assaulted until the point of death. Moreover, disproportionate levels of poverty are pervasive for persons of African descent and Black Europeans, who also experience great disparities in education, employment, healthcare and housing.

The ODIHR also recognizes the implicit and explicit biases against Muslims as well as Roma and Sinti populations. Throughout Europe, ethnic hatred and anti-Roma rhetoric such as “Gypsy criminality” are widespread, as are anti-Muslim sentiments connected to terrorism and extremism. The 2015 report detailed 63 attacks on Roma and Sinti persons and 677 attacks on Muslims. In Austria, for example, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported a kidnapping of a Roma woman “who was driven by two men pretending to be police to a nearby forest.” In the Netherlands, there were 439 reported hate crimes against Muslims, with many targeting mosques using graffiti and desecration.

Despite pervasive violence and non-inclusive policies, marginalized groups in Europe are continuing to mobilize. Racism, Islamophobia and concerns about anti-immigration and anti-integration are not new phenomena in Europe, and non-governmental organizations and civil society contributors, such as the European Network Against Racism (ENAR); the Faith Matters, Tell MAMA (Measuring Anti-Muslim Attacks) campaign in the United Kingdom; Stopp Diskrimineringen (Stop Discrimination) in Norway; and the Regionalni Centar za Manjine (Regional Centre for Minorities – RCM) in Serbia, are telling of the racialized inequities that persist in European societies. However, with the rise of Trump and European far-right platforms, political mobilization and resistance against the global order of fascism has increased. “Sister marches” in Europe, in solidarity with the Women’s March on Washington, D.C., were held in Berlin, Paris, Rome, Vienna, Geneva and Amsterdam. In February, protests galvanized thousands in opposition to Trump’s travel ban, in cities from Berlin to London, where protesters shouted, “Theresa May, shame on you!” after May invited Trump to visit Britain. In 2016, Black Lives Matter protesters in London, Berlin, Amsterdam and the Netherlands, in conjunction with those in the U.S., brought attention to police brutality and racialized state violence after the shooting deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile.

Here, in understanding the global implications of Trump, it is imperative to examine the power of global political mobilization and solidarity. Now, more than ever, it is time to challenge these neo-fascist regimes and assess the global, intersectional threat to race, religiosity, immigration and national and cultural citizenship. Fascism knows no bounds. Therefore, global resistance cannot simply be a one-time ordeal. The historical groundwork laid by U.S. and European transnational activists serves as a formidable platform for contemporary resistance efforts to build upon. If Trump, his European far-right allies and international fascism are to be stopped, we must follow the mantra of the great Audre Lorde: “Revolution is not a one-time event.”

*This article is published in collaboration with Truthout.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.