The Distinct Nature of Black Eco-poetry

Recently an Africana Studies colleague at Luther who studies African and African American literature brought the poet Camille Dungy to my attention. He thought I should see if I could use some of her poetry in her Suck on the Marrow published by Red Hen Press in 2010 in my African American History Survey. Here is the publisher’s summary:

Set in Virginia and Philadelphia during the mid-19th century, Suck on the Marrow traces the experiences of self-emancipated bondswomen, kidnapped Northern-born blacks, free people of color, and the slaves of a large plantation and small household. The interconnected narratives of six fictionalized characters use traceable dates, facts, and locations to investigate moving aspects of American history. These poems explore the interdependence between plantation life and life in Northern and Southern American cities, and the connections between the successes and struggles of a wide range of Americans, free and slave, black and white, Northern and Southern.

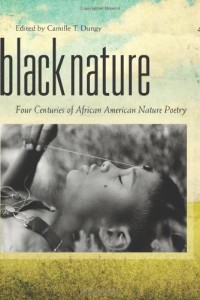

In doing some research on Dungy, I found something super exciting for my research. She edited the volume Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry and wrote an introduction contemplating the way African Americans have discussed their environments distinct from Anglo American nature poetry and, for that reason, something that must be included in the current renaissance of eco-poetry.

In doing some research on Dungy, I found something super exciting for my research. She edited the volume Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry and wrote an introduction contemplating the way African Americans have discussed their environments distinct from Anglo American nature poetry and, for that reason, something that must be included in the current renaissance of eco-poetry.

Here is a snippet from page xxi of the introduction that I found particularly intriguing:

The traditional context of the nature poem in the Western intellectual canon, spawned by the likes of Virgil and Theocritus and solidified by the Romantics and Transcendentalists, informs the prevailing views of the natural world as a place of positive collaboration, refuge, idyllic rural life, or wilderness. The poetry of African Americans only conforms to these traditions in limited ways. Many black writers simply do not look at their environment from the same perspective as Anglo-American writers who discourse with the natural world. The pastoral as diversion, a construction of a culture that dreams, through landscape and animal life, of a certain luxury or innocence, is less prevalent. Rather, in a great deal of African American poetry we see poems written from the perspective of the workers of the field. Though these poems defy the pastoral conventions of Western poetry, are they not pastorals? The poems describe moss, rivers, trees, dirt, caves, dogs, fields: elements of an environment steeped in a legacy of violence, forced labor, torture, and death.

The next page continues in this compelling vein of defining the way black poets have written about their environment, including their urban one, in a way that should be considered eco-poetry but also explodes the boundaries set up by the Western canon.

This relates to my research as I continue to think about the place for Juliette Derricotte‘s joy in the natural world within my book chapter on her 1928-29 trip around the world. Various readers have questioned whether her repeated and long descriptions of the beauty surrounding her are as interesting as the few times she commented on the politics around her. I find both intriguing, but I am still pondering how to merge them effectively.

Below are a few things I’ve considered, but out of them all (except the Christianity piece, which I’ve not yet fully explored) I think Dungy’s Black Nature is the most promising.

- Immanuel Kant’s musings on aesthetics, a text in which he claims that only white men can appreciate the sublime, the highest form of the experience of beauty, which he also links to morality. Black people and all women cannot reach the sublime and only experience beauty at lower levels. And yet, I don’t know that it is worth engaging in this in my work. Derricotte did not speak of the beauty of the sunsets in India in order to somehow prove her worth to Kant, because she showed no indication of having read him. Someone else could perhaps use her letters to disprove Kant, but surely that is no longer a valid line of academic research?

- The way tourists describe the landscape around them and how many Western tourists/colonizers/naturalists tend to lump the people they meet into those landscapes (when they describe the people at all, instead of presuming the landscape is somehow “empty” and ready for Western colonization). This has helped me quite a bit in thinking about how a person of color embedded in a Western context would share and/or challenge those ideas. I used James Campbell’s description of how Du Bois acted in Liberia in Middle Passages: African American Journeys to Africa, 1787-2005 to help think about how these ideas might apply to a black America. At the same time, some of my African American history colleagues find it odd to put Derricotte within the same sphere as white colonial tourists, a critique I am still working through.

- Experience of beauty as a form of resistance, as raised by the passage of Alice Walker’s Color Purple that she drew her title from.* Shug walked with Celie out into a field of purple flowers and asked her to soak in the vision and feel of them to give her the strength and resiliency to continue on in an impossible life. She told her,

Yes, Celie, she say. Everything want to be loved. Us sing and dance, make faces and give flower bouquets, trying to be loved. You ever notice that trees do everything to get attention we do, except walk?

Well, us talk and talk bout God, but I’m still adrift.

Trying to chase that old white man out of my head. I never truly notice nothing God make. Not a blade of corn (how it do that?) not the color purple (where it come from?). Not the little wildflowers. Nothing.

Now that my eyes opening, I feels like a fool. Next to any little scrub of a bush in my yard, Mr. ____’s evil sort of shrink. But not altogether. Still it is like Shug say, You have to git man off your eyeball, before you can see anything a’tall.

- Derricotte attributed the profundity she saw in nature to God’s grace–the role of nature in African American Christianity is something I plan to explore but have not yet. I’m familiar with the beauty of nature being used as a justification for God’s existence in some Christian traditions, but I don’t know how important it is in the type of AME and social gospel theology Derricotte ascribed to.

And yet, giving full space to all of these would distract from the rest of the chapter. Good questions to ponder at the start of summer writing season!

*You can read my original meditation on this here.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.