The Radical Hope of Octavia Butler

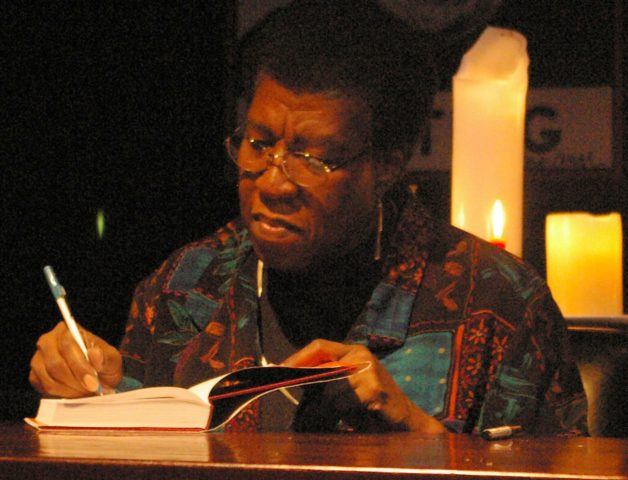

When I assigned Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower for my Introduction to Fiction classes this fall, I was fearful that this novel, set in the 2020s featuring a young Black girl who lives in a violent, dystopian America suffering from social, ecological, and political collapse, might feel too close for comfort. This season ended up bringing a fresh round of tragic gun massacres, two ominous reports on climate change from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP), plus all of the ongoing nonsense emanating from the racist administration in Washington, DC, which continues its free-fall into a third year. Then in November, a deadly wildfire ravaged Southern California, the setting of Parable of the Sower, claiming the lives of dozens of people and giving us a glimpse of California’s ecological future. Several Octavia Butler fans on social media noted the similarities between the burnt-out California that Butler depicts in Parable of the Sower and the real-life images of burned, abandoned cars littered on the roadsides near charred forests.

I assigned Parable of the Sower because it is an exemplary novel that would allow us to explore some of the core elements of fiction, which is the purpose of the course. But on another level, I assigned the novel as a way to think about survival in these trying political times. “I intend to survive,” Lauren Oya Olamina declares throughout the narrative. But what does that mean for us now? Octavia Butler frequently mentioned her own personal tendencies toward pessimism. If anything, the Parable books are known for their bleakness and despair. The fictional Los Angeles suburb of Robledo where Lauren grows up, and where her Baptist minister father was the leader, ends up being attacked by outsiders, forcing Lauren and the other survivors to flee for their lives. However, Butler also laced a radical hopefulness into the narrative that with forethought and strategy, even under the bleakest circumstances, this group might be able to survive and create something new.

Self-defense is a major part of Lauren’s strategy for survival in Parable of the Sower. “A well-armed society is a polite society,” says our contemporary gun fetishist, but Butler paints a stark portrait of what a threatening “open carry” society would actually look like. And there is nothing polite about it. At the same time, Parable includes principled arguments for self-defense, especially for vulnerable populations. Lauren suffers from hyperempathy syndrome, a psychological condition in which she can feel the pain and pleasure of others. Therefore, she has to be careful about how she inflicts pain. And when she does have to kill, she has to make sure that the shot is fatal, lest she be incapacitated by the pain of the victim dying. Lauren and her crew do not wish to initiate harm on their journey northward, nor do they want to take advantage of the vulnerable. But they are also ready to kill in order to protect themselves from the sociopaths that they have to confront on the road.

In Marlene Allen’s 2009 Callaloo article, “Octavia Butler’s ‘Parable’ Novels and the ‘Boomerang’ of African American History,” Allen borrows Ralph Ellison’s idea of the “boomerang of history” (from Invisible Man) and applies it to Parable of the Sower. The narrative of progress is a seductive one. Well-meaning liberals insist that racism will eventually die off, even as the evidence of young men joining fascist movements across the world sits right in front of us. Butler’s Parable depicts a future America in which there is rampant illiteracy, forms of enslavement have returned, and young women are bartered as property. Though her work often feels prophetic, Butler was extrapolating from already existing forms of exploitation in her fictional portraits of the future, ongoing political efforts to strip women of all reproductive rights, continued exploitation and abuse of undocumented workers, to the unchecked powers that corporations hold over human beings and the environment.

Gerry Canavan’s 2016 biography of Octavia Butler provides background on how Butler composed the Parable series comprised of Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1998). Canavan draws out Butler’s dichotomy of YES-BOOKS vs. NO-BOOKS and discusses how the draft versions of her novels were often more bleak, violent, and unforgiving than the finished versions she eventually published. Unfortunately, Butler’s untimely death in 2006 deprived us of seeing the next planned book in the series, Parable of the Trickster. Canavan’s account shows Butler struggling with the narrative of Trickster, which was to take place on a distant, Earth-like planet named Bow, where Lauren Olamina’s vision that “The destiny of Earthseed is to take root among the stars” becomes a reality for a new generation of humans. As Canavan puts it, “Butler realized that living in outer space would be so difficult and so miserable that it would require a new idea of human solidarity: people would have to work together to an extent that actual human history (and, perhaps, actually existing human biology) had never before allowed.” In this way, the entire Parable project is a radical thought experiment that asks, what values would humanity need to adopt in order for the species to advance instead of die out?

The most hopeful part of Parable of the Sower, what ultimately makes it a YES-BOOK, is that Lauren realizes it is not enough just to live day-to-day. She also dreams of creating a better future for herself and the next generation. As she works out her Earthseed beliefs in her journals, she writes, “God is Change, and in the end, God prevails. But God exists to be shaped. It isn’t enough for us to just survive, limping along, playing business as usual while things get worse and worse. If that’s the shape we give to God, then someday we must become too weak – too poor, too hungry, too sick – to defend ourselves.” Through Lauren’s story, Butler stresses the need to think about building different tomorrows, even as we struggle to survive today.

At a recent talk at Strand Book Store in NYC, the author N.K. Jemisin urged the audience in the strongest possible terms to go out and read Parable of the Sower now, because this is the book that describes our present political condition. Jemisin alluded to the end of Parable of the Sower, where Lauren, her new husband Taylor Bankole, and the rest of the crew who joined them on their journey, have settled onto Bankole’s land in Northern California to form the Acorn community. Readers who have read the continuation of that story in Parable of the Talents know that Acorn will not remain an oasis forever. After a short period of relative tranquility, their community would be sacked by vigilantes inspired by the new white Christian nationalist President Andrew Jarret who promises to “Make America Great Again.” Octavia Butler made Parable of the Sower a YES-BOOK by instilling in Lauren a sense of hope that she could apply her intelligence, spirit, and energy to help shape a different future for herself, for her community, and for the daughter that she would eventually have in Parable of the Talents who tells the story of her parents’ struggles. The radical hope that Octavia Butler offers is not based on inevitable, linear progress, but in the belief in our own agency in the matter—that through our present actions, with planning and persistence, we can lay the foundations for a better tomorrow.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.