The Pragmatism of Black Nationalist Women’s Global Politics

*This post is part of our online roundtable on Keisha N. Blain’s Set the World on Fire

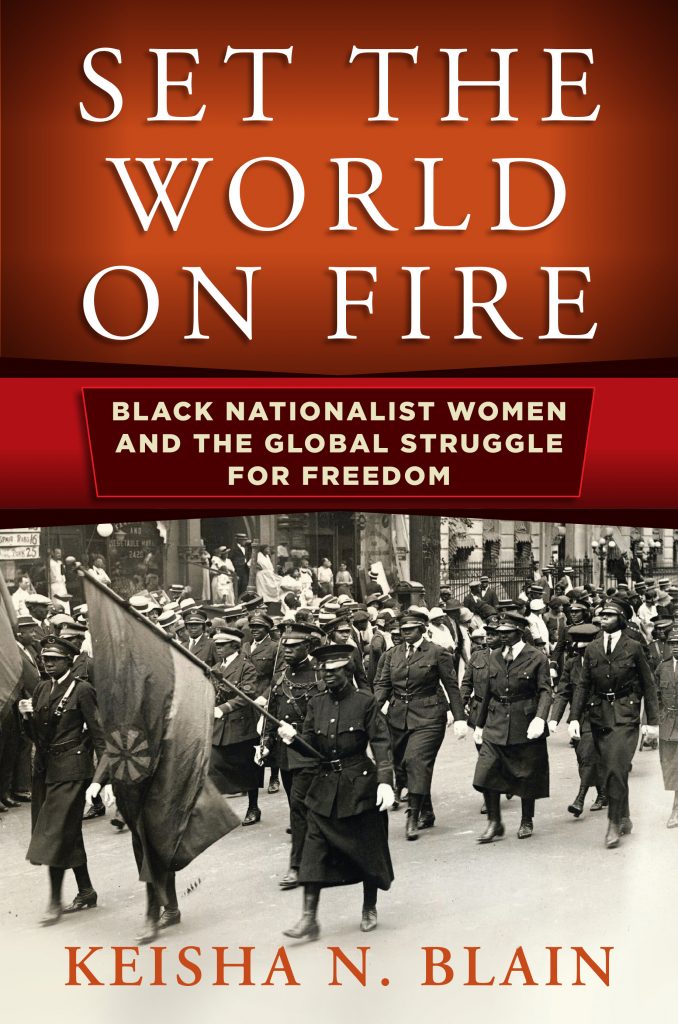

Keisha N. Blain’s fabulous new book Set The World On Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom tells the compelling story of Black nationalist women in the United States, England, the Caribbean, and West Africa who sought to end global white supremacy. Of course, civil rights groups like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), clubwomen’s organizations like the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) and Marxist-oriented Blacks also aimed to end racial domination. But these Black nationalist women distinguished themselves with their particular emphasis on Pan-African solidarity, Black self-determination, African emigration and, in some controversial cases, strategic alliances with white supremacists.

Set the World On Fire is a pointed rejoinder to androcentric histories of Black nationalism and Pan-Africanism. Blain excavates and analyzes the politics and political imagination of Black women like Maymie De Mena, Amy Ashwood Garvey, Amy Jacques Garvey, Mittie Maude Lena Gordon, Adelaide Casely Hayford, and Laura Kofey, who fought on multiple fronts against global white supremacy, elitist respectability politics, and toxic conceptions of Black masculinist nationalism. Blain casts these “proto-feminists” as forerunners to contemporary feminist movements, as they rejected conceptions that exclusive male-centered leadership and the recovery of Black manhood rights was a prerequisite to Black nationality.

Many of these women cut their political teeth within the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), the largest Black-led political organization in world history. By spotlighting these Garveyite women in Africa, the Caribbean, and the Americas, Blain expands the chronologies and geographies of Garveyism beyond ‘rise and fall’ narratives of Marcus Garvey and the New York-centered UNIA, thereby bringing new depth and dimension to the study of global Garveyism. Garvey’s first wife, Amy Ashwood Garvey, was the UNIA cofounder and leading organizer of the UNIA shipping company, the Black Star Line and the UNIA newspaper, Negro World. His second wife, Amy Jacques Garvey, despite sexist resistance from some UNIA men, edited the landmark “Our Women and What They Think” Negro World column and effectively ran the UNIA while Garvey was imprisoned on trumped-up mail fraud charges. Long after the UNIA’s 1920s heyday, both women remained pivotal figures in the anti-colonial Pan-Africanism that helped lead to African, Asian, and Caribbean independence in the 1950s and 1960s.

Despite the UNIA rallying cry of “Africa for the Africans,” scholars of Garveyism, Black nationalism and Pan-Africanism often evoke Africa and Africans as obligatory reference points in histories of Black people outside of Africa. By contrast, Blain’s discussion of African women like Adelaide Casely Hayford, along with African-based women like Amy Ashwood Garvey, who lived in Liberia in the late 1940s, are welcome examples of her abilities to bring Africa and Africans into the largely diasporic stories of Garveyism and Black nationalism.

In recovering the rich histories of strategic and resourceful Black nationalist women leaders and rank and file members, Blain also recovers the histories of supposedly dormant Black nationalism between the 1920s UNIA and the 1960s rise of Black Power. In doing so, she revises previous assumptions that “the golden age” of Black nationalism ended with the mid 1920s decline of the UNIA.

Blain’s discussion of Mittie Maude Lena Gordon is particularly fascinating to read. Confronted with the harsh realities of seemingly impregnable US Jim Crow, overseas American political, military, and economic domination over people of color, and European colonialism in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean, Gordon established the Peace Movement of Ethiopia (PME) in 1932. Influenced by an eclectic mix of Garveyism, Islam and the Moorish Science Temple of Noble Drew Ali, the PME boasted 300,000 supporters, the largest and most influential Black nationalist movement of the 1930s. Part of a longstanding emigrationist Black nationalist tradition that began in the early 19th century, the PME vigorously pursued emigration to Liberia. In 1933, Gordon sent a petition signed by 400,000 Blacks who wanted out of white supremacist America, particularly from the undemocratic and authoritarian one-party regime of the Jim Crow South.

But in a puzzling paradox, Gordon, like Marcus and Amy Jacques Garvey, entered into a strategic alliance with white supremacists like US Senator Theodore Bilbo and author Ernest Sevier Cox, to further their emigrationist goals. Gordon hoped to leverage the political power and popularity of Bilbo and Cox, to help the US Congress pass the 1939 Greater Liberia Bill, which would have provided government funding for the emigration and settlement of willing Black Americans to Liberia. She also maintained a lengthy correspondence with Cox that seemingly reflected genuine personal affection between these two unlikely allies. Blain tells this story with subtle sensitivity. Rather than dismissing Gordon as hopelessly deluded and politically naïve, Blain emphasizes the hard-edged pragmatism of Gordon, chronicling her difficult navigation of these treacherous waters. She explained to followers who doubted these questionable alliances, “when we have to depend on the crocodile to cross the stream we must pat him on the back until we get to the other side” (124).

In conversation with recent path-breaking work on Afro-Asian ties and a “Black Pacific,” Blain tells of Gordon’s Afro-Asian solidarities centered on an ascendant, imperialist Japan as a potential champion for people of color worldwide. Gordon’s alleged declaration that the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor symbolized that “one billion Black people struck for freedom,” and her exhortations for PME members not to fight in the US military eventually led to FBI investigations, a conviction for sedition and conspiracy, and a two-year jail term that effectively halted her emigrationist program.

Blain is careful to show that trafficking with ardent white supremacists was not the only problematic aspect for some of these anti-colonial Pan-African women. Blain describes them as “proto-feminists” because even as these women battled against sexist Black men to create space for female political leadership, they sometimes simultaneously reproduced gendered roles and patriarchal notions of Black leadership. As an aside, this reader wondered how Blain’s persuasive concept of “proto-feminism” was distinct from Ula Taylor’s notion of “community feminism” to describe Garveyite women or to Lorelle Semley’s concept of public womanhood to describe politicized West African women.

Blain also notes the troubling fact that Gordon, Amy Ashwood Garvey, and others, like countless diasporic Blacks before, during and after their time, viewed Black emigration to Africa as the means to ‘civilize’ and ‘uplift’ Africans. Of course, across the globe, there have, and continue to be, enduring stereotypes of Africa as a timeless ‘Dark Continent’ featuring jungle landscapes, roaming animals, and primitive, war-mongering ‘tribes’. Ironically, in the case of the PME, it was Liberian President Edwin Barclay who set the terms for diasporic Black emigration. He would only accept emigrationists who were “skilled artisans, trained agriculturalists, business men with capital, and young physicians” and who brought at least $1,000 to Liberia to prove their financial solvency. Even as Blain brings these women’s stories to center stage, she notes too that in some ways, they remained on the margins of Black America, since the vast majority of Blacks did not want to emigrate to Africa. After 1957, diasporic Black emigration bypassed Liberia, with its relatively conservative, pro-American leadership, in favor of the more explicitly Pan-Africanist new African nations of Ghana and Tanzania (and much later, post-apartheid South Africa). But ultimately, these women deserve credit for keeping the emigrationist impulse alive in the years between the UNIA’s apex and African decolonization.

Blain tracks the Pan-African travels of women like Amy Ashwood Garvey as they moved across the Americas, the Caribbean, Europe and Africa. But, mindful to the fact that many of these working class women did not have the resources to move across national borders, Blain also emphasizes the global circulation of their words and ideas in Black print culture and the connectivity of their American-based organizing traditions to their transnational programs. For instance, PME leader Celia Jane Allen’s emigrationist campaigns in Mississippi between 1937 and 1942 was embedded in a longstanding grassroots Black organizing tradition that dated to the 19th century and became more visible during the 1960s, as detailed in Charles Payne’s classic, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom. Through the example of the PME, Blain also reminds us of two other longstanding Black nationalist traditions: the importance of Islam, in addition to liberationist Christianity, as a powerful religious influence in Black nationalism; and, with the PME’s Protective Corps, the lengthy tradition of armed self-defense in Black freedom struggles.

Blain, like Dayo Gore, Rhonda Williams, Barbara Ransby, and others before her, also reminds us of the essential need to go beyond traditional government or institutional archives to recover and analyze Black women’s activism. Very often, Black women created their own archives with their cultural production, including plays, poetry, and song, for example, their writings, ephemera and their oral histories. Indeed, in bringing together so much material from a great variety of institutional and personal archives, Blain necessarily created her own archive of original material to tell the stories of these extraordinary women. Blain’s dogged research allows her to fruitfully integrate the histories of African and diasporic Black women’s political activism, unlike other studies of Black Internationalism that largely bypass Africa and Africans. She also offers a powerful counter-example to androcentric histories hopelessly impoverished by the fact that they ignore women, over half the human population. In excavating lesser-known histories of Black women’s activism in grassroots Garveyism and other Black nationalist and Pan-Africanist movements between the 1920s and 1960s, Set the World On Fire also reveals new horizons and histories, and perhaps too, a heretofore hidden “golden age” of Black nationalism.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

The late Dr. Manning Marable often emphasized that the Pan-African movement can be revitalized if deferred to the woman in the movement, to paraphrase him from a lecture I heard at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the early 90s, Pan-Africanism must be filtered through Black woman leadership. I wholeheartedly agree and salute you for a well-written review.