The NFL’s Denial of Black Humanity

In response to protests that rocked the national sports world, NFL owners have approved a new policy that requires players and personnel to stand for the National Anthem while on the field. They provided the option for them to stay in the locker room. However, if they kneel or sit down on the field, they will be fined.

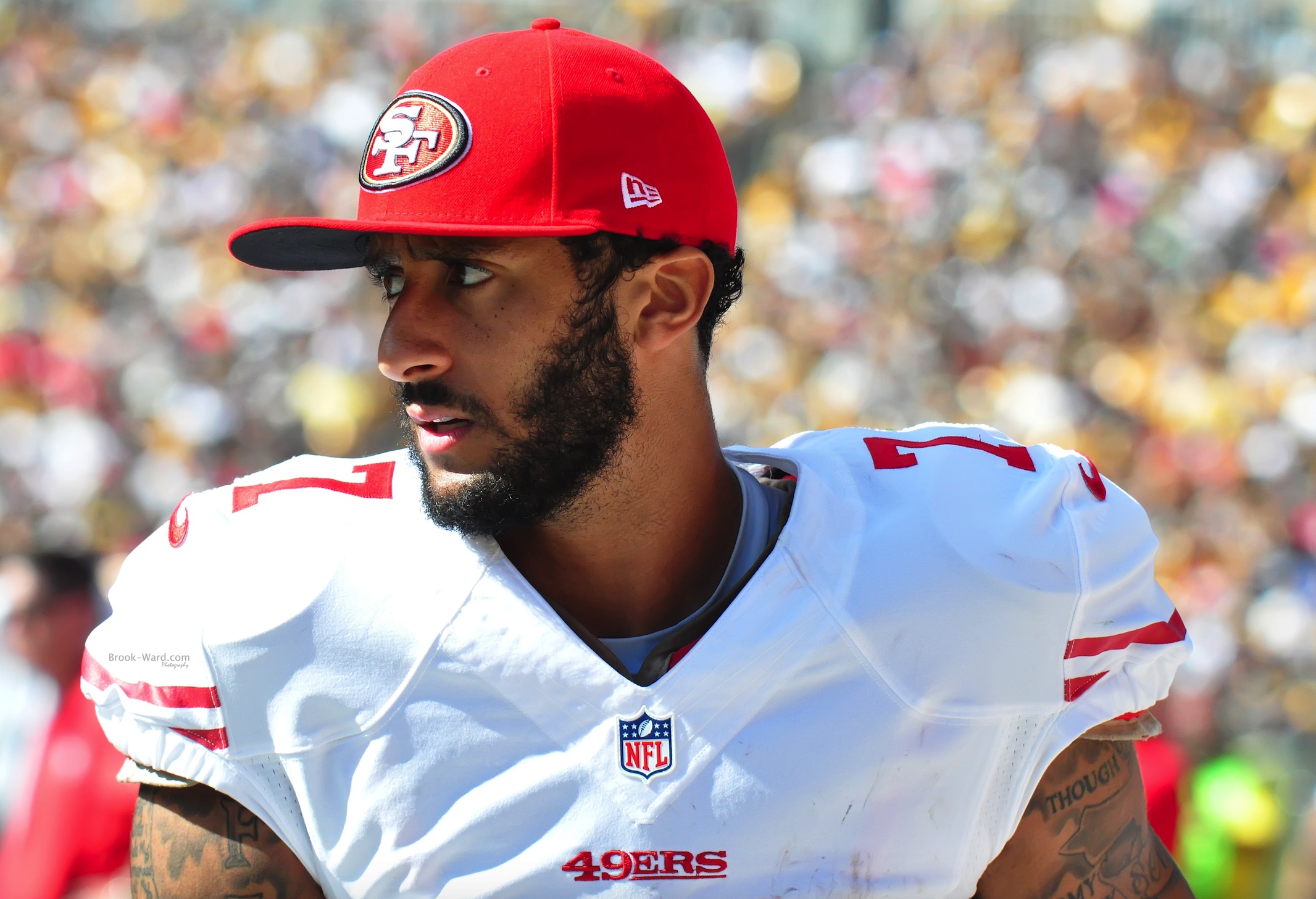

The draconian change comes in response to the two year old protests initiated by Colin Kaepernick, who initially sat, then began to kneel during the playing of the National Anthem to protest “a country that oppresses Black people and people of color.” A host of athletes followed Kaepernick’s lead, generating a range of reactions about the relationship between sports and politics in the NFL and beyond. Instead of addressing the heart of Kaepernick’s protest, the NFL has stuck a knife through it. They shot down the very discussion of Black humanity, and Black humanity itself.

The “anthem protests” began as a radical critique against the institutional racism of the United States. But they were quickly rechanneled into conversations about constitutional rights, collective bargaining, and labor politics.

These issues are certainly connected. When Black athletes started their protest, they used their First Amendment right to speak freely and “petition the government for a redress of grievances.” And it is also true that NFL owners did not consult the NFL Players Association (NFLPA) about the recently passed “anthem policy,” and sports writers have justifiably cried out against the violation of their labor rights.

The denial of Black humanity is a radically different discussion than the denial of Black civil rights. The call to restore and protect the constitutional rights of Black people, assumes that Black people, including Black athletes, have an uninhibited path to claim and take advantage of such rights. Yet, in all this discussion, we seem to have forgotten one thing: Black people have always occupied an ambiguous, and at times nonexistent, relationship to meaningful citizenship rights. Since its inception, the United States has denied Black people their civil and human rights.

Given this history, the NFL’s new anthem policy should not be surprising. It’s a simple equation. Anytime Black people expose the injustices of the United States, the United States becomes more unjust. In fact, the NFL’s actions are akin to the government’s crackdown of Black radicals during the early years of the Cold War. During this period of heightened anti-Communism, Black activists—including Paul Robeson, W.E.B. Du Bois, Claudia Jones, and a host of others—who called attention to the dehumanizing oppression of Black people throughout the world, were quickly silenced by the U.S. government. As historians Mary Dudziak, Carol Anderson, Penny von Eschen and others point out, the United States during this period engineered a more civil and domestic based struggle–one around rights rather than humanity. If Black people wanted to be seen and heard, they were expected to behave appropriately and represent the nation accordingly. Otherwise, they were punished or silenced. The disciplining of Black protest transformed a radical, globally conscious Black politics to a domesticated one.

The relationship between Jackie Robinson and Paul Robeson exemplifies this point. Robeson, a former college football star at Rutgers University and avid anti-colonialist, became a critic of the United States’ racist domestic and foreign policies during the Cold War. In April 1949, he delivered a speech at the Paris Peace Conference, where he allegedly said that African Americans would not support the United States in a war against the Soviet Union. He clarified in a later interview that his speech “was not anybody going to war against anybody,” but rather that Black people from Louisiana to Alabama, from the West Indies to Africa, would “fight for peace so that new ways can be opened up for a life of freedom.” Paul Robeson exposed the structural racism that subordinated Black people to second-class citizenship.

Shortly thereafter, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) led by Joseph McCarthy, labeled Robeson a Communist, and brought in Robinson to testify against him in July of 1949. Robinson distanced himself from Robeson’s radical politics and denounced Communism. Yet he nevertheless assailed U.S. racism and suggested that African Americans could reject American democracy if not remedied. Indeed, Robinson argued that Black people “were stirred up long before the Communist Party, and they’ll stay stirred up long after the Party has disappeared.” Importantly, this case demonstrates how Black athletes have been at the center of debates about the shape and form of Black politics—radical or civil, rights or humanity.

Today the NFL owners’ decision mirror the actions of Joseph McCarthy. Similar motivations—to censor Black radical protest, and shift attention away from the systemic racism of the United States—guided the decisions of NFL owners to implement the anthem policy. The NFL colluded against Kaepernick and his politics in favor of a more acceptable politics that is apparently resolved by monetary donations and progressive press releases. Indeed, if the politics of Black athletes were to be taken seriously, they would either have to “shut-up and play” or stay in the locker room.

Kaepernick and others were protesting the unjustified, yet seemingly normalized, killings of Black people in this country. In this light, Kaepernick’s protests represented a radical Black politics that sought to reveal the systemic anti-Blackness of this country and its investment in the dehumanization of Black peoples. By introducing a policy that censors Black radical politics and penalizes athletes for denouncing the foundational anti-Blackness of the United States, the NFL is, in effect, denying the humanity of Black people in this country.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.