The Mysterious Thelma X and the Struggle of Black Domestic Workers

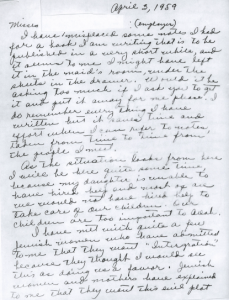

Several years ago, I was looking through the papers of sociologist C. Eric Lincoln at the Robert W. Woodruff Library at Atlanta University Center when I came across a handwritten letter addressed to “Misses ________: (employer).” Someone (Lincoln, the author, or the mysterious recipient) had cut the name from the document. Written in 1959, the letter first appears as a simple request to forward some misplaced notes; the author directs her employer to “the maid’s room, under the sheets in the drawer.” But, noting that she may not be back for some time, as her “daughter is unable to have hired help and most of all we would not have hired help to take care of our children,” the letter suddenly shifts into a forceful critique of black domestic labor:

Several years ago, I was looking through the papers of sociologist C. Eric Lincoln at the Robert W. Woodruff Library at Atlanta University Center when I came across a handwritten letter addressed to “Misses ________: (employer).” Someone (Lincoln, the author, or the mysterious recipient) had cut the name from the document. Written in 1959, the letter first appears as a simple request to forward some misplaced notes; the author directs her employer to “the maid’s room, under the sheets in the drawer.” But, noting that she may not be back for some time, as her “daughter is unable to have hired help and most of all we would not have hired help to take care of our children,” the letter suddenly shifts into a forceful critique of black domestic labor:

“I am a Muslim mother and editor of my own magazine with an understanding of the true meaning of Integration and I know how a mother feels inside about her own children whom she loves dearly . . . I have no worry I have the solution and [sic] the mothers who are responsible. Negro mothers will know the same in a very short while. Allah is God and he is black, and he will fight and save our children at any cost to your entire race.”

The author added that if “your next maid is a Negro woman or a gentile woman she will by then have received a book written by me (a maid) and this will enable her to see you and see other Jewish women for what you realy [sic] are.1

The letter was signed: “Thelma, the maid.”

Although not much is known about Thelma X, Lincoln listed her in his seminal work on the Nation of Islam (NOI), The Black Muslims in America, as one of the group’s most important women figures, alongside Lottie X and the late Tynetta X Denear. In part, her letter addressed the silences within the predominantly-white women’s movement in addressing the plight of black women laborers. As Angela Davis has noted, white women have “rarely been involved in the Sisyphean task of ameliorating the conditions of domestic service. The convenient omission of household workers’ problems from the programs of ‘middle-class’ feminists past and present has often turned out to be a veiled justification – at least on the part of the affluent women – of their own exploitative treatment of their maids.”2 But Thelma X’s letter to her white employer also offers one answer to the question posed by Manning Marable in his biography of Malcolm X: “What attracted so many intelligent, independent African-American women to such a sect [as the NOI]?”3

The desire to interrogate the patriarchy of black nationalist movements such as the Nation of Islam, has resulted in a flattening of the experiences of women regardless of class, race, and sexuality. Some have argued that black feminism arose out of their experiences of misogyny and marginalization by women within social movements, especially Black Power. While those experiences surely existed, Stephen Ward importantly argues that articulations of black feminism should not be seen outside the Black Power Movement, but rather as “a form of it.”4

Thelma X’s letter helps us understand both the relationship between the predominantly-white women’s movement and black women as well as the appeal of black nationalism to many women, especially those in household labor. While white middle-class women in the postwar period felt bounded by the home and sought opportunities in the workplace, many working black women labored long hours for low wages, preventing them from spending time in their own households. The “home” was not necessarily a place of burden and patriarchal constriction for black women then, but rather a privilege of whiteness they were not afforded. As Davis points out, under slavery, a black woman’s domestic labor in her own home was “the only labor of the slave community which could not be directly and immediately claimed by the oppressor.”5 As Thelma X wrote to her white employer: “You can get some one [sic] else to work for your children and you, I will not have time, I must save my own and the children of our race.” A shared struggle between white and black women was that both were striving to leave the same domestic space: the white home.

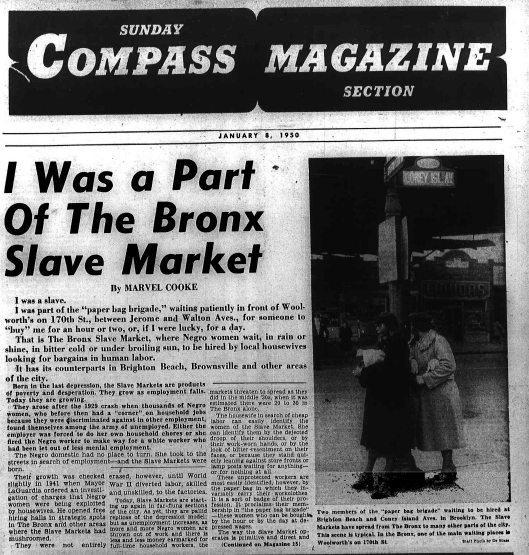

As Tera Hunter has demonstrated, domestic labor in the 19th century was combined with Jim Crow in the South to produce the “contradictory desires among urban whites striving to distance themselves from an ‘inferior race,’ [while depending] on the very same people they despised to perform the most intimate labor in their homes.”6 When leaders of the National Association of Colored Women in the South drafted concerns in 1919, they listed the conditions of domestic workers first. In 1935, the struggle of domestics in New York was documented by Ella Baker and Marvel Cooke in their investigative report on what they called the “Bronx Slave Market.”

They described an unregulated market in which black women stood for hours each day on the busiest corners in the Bronx waiting for work. She who “is fortunate (?) enough to please Mrs. Simon Legree’s scrutinizing eye is led away to perform hours of multifarious household drudgeries,” they wrote. “Under a rigid watch, she is permitted to scrub floors on her bended knees, to hang precariously from window sills, cleaning window after window, or to strain and sweat over steaming tubs of heavy blankets, spreads and furniture covers.” According to the 1940 census, nearly 60% of working black women were employed in domestic labor.7

As Margo Natalie Crawford has argued, for the NOI and other black nationalists, women’s “bodies were too often the medium for black male dreams of a nation-state; their bodies were often the canvas for the geography of Black Power.”8 Indeed, Elijah Muhammad once queried, “Who wants a sterile woman? . . . No man wants a non-productive woman.”9 However, there were nevertheless various reasons why black women, domestic workers in particular, were drawn to the Nation of Islam. The first was that the NOI was strategic about its appeal to this segment of workers. Thursday night, the weekly meeting night for the all-women’s Muslim Girls Training and General Civilization Class (MGT-GCC), was the traditional night off for domestic laborers. Second, the NOI provided support for domestic workers, especially those who faced difficult circumstances during the 1960s. The Amsterdam News reported that when several young southern black women responded to ads to come North to work for $55 a week only to be told to go “out into the street and find somewhere to stay,” Malcolm X and other community activists came to their aid. The journalist in charge of breaking the story later recalled that it was during this period that he first met Malcolm. “Assigned to do the story, I went to the downtown agency and then across the street to a restaurant where some food was found for the girls. Malcolm X was there, as well as the Manhattan NAACP attorney and [radio host] Leon Lewis of WWRL.”10

Thelma X’s letter came at a crucial moment in the long history of labor organizing by domestic workers. As Premilla Nadasen notes in her important new work on the history of household workers’ struggles, the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott best embodied “emerging domestic worker agitation” in the civil rights movement.11 The following year, Alice Childress published a series of stories written about domestic labor called Like One of the Family: Conversations from a Domestic’s Life. Like Thelma X, the protagonist of Childress’ story, Mildred, wrote that contrary to her white employers’ insistence to a white friend that she was indeed “one of the family,” she was made to eat in the kitchen while the woman’s puppy slept on her satin spread. “So,” she wrote, “you can see I am not just like one of the family.”12 As labor organizer Carolyn Reed put it in a recent interview, “I don’t need a family, I need a job.”

- Thelma X to unknown, April 3, 1959, Box 278, Folder 27, C. Eric Lincoln Collection, Robert W. Woodruff Library, Atlanta University Center. ↩

- Angela Davis, Women, Race, and Class, 96. ↩

- Manning Marable, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, 143. ↩

- Stephen Ward, “The Third World Women’s Alliance: Black Feminist Radicalism and Black Power Politics,” 120. ↩

- Davis, 17. ↩

- Tera Hunter, To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors after the Civil War, 105. ↩

- Davis, 92 and 98. ↩

- Margo Natalie Crawford, “Must Revolution Be a Family Affair? Revisiting The Black Woman,” 196. ↩

- Quoted in Jennifer Nelson, Women of Color and the Reproductive Rights Movement, 96-97. ↩

- “Malcolm X Helped Stranded Workers,” Amsterdam News, February 27, 1965. ↩

- Premilla Nadasen, Household Workers Unite: The Untold Story of African American Women Who Built a Movement, 18. ↩

- Nadasen, 9. ↩

Working as domestic help for black women is little better than slavery. Oppression in whatever form it takes, is akin to slavery.