The Modern Black Convention Movement and Black Youth Leadership

*This post is part of our online roundtable celebrating the 20-year anniversary of the publication of Komozi Woodard’s A Nation Within a Nation

On July 21, 2018, historian Komozi Woodard used his platform at the Civil Unrest and Economic Conditions before 1968 panel to center the conversation on the significant role of Black youth in postwar U.S. social movements. Woodard opined, “The Black student unions are probably the most important thing we should be looking at, and particularly, the high school students who have been left out of the stories.” Ensuring that attendees departed the event with a charge of their own, Woodard highlighted the need to support young people in our current moment, stating that “we need to give them the resources to step up and assume the leadership.”

As a scholar of Black youth politics, I view A Nation Within a Nation: Amiri Barka (LeRoi Jones) and Black Power Politics as not only a bridge between author Komozi Woodard’s personal experiences as an activist in Newark and his scholarship as a historian of social movements. I also see it as a creative conceptual framework for the rigorous study of Black youth activism. While the movement was multi-generational and included welfare mothers and educators, the historical actors who are at the heart of Woodard’s account were largely teenagers and young adults under the age of thirty when they became politically active. In other words, although we have understood this foundational text to be a history of the Black Power and Black Arts movements, I would argue that it was also one of the first books to take Black youth politics seriously.

A Nation Within a Nation made three critical contributions to our understanding of Black youth politics and activism, most of which scholars have only spottily engaged. First, it revealed the importance of the Modern Black Convention Movement (MBCM) in the development of Black leadership among high school and local youth, as well as the ways in which young people contributed to the movement itself. For example, Woodard examined the political work of the Black Youth Organization (BYO), the New Ark Student Federation, and CFUN’s youth members. Second, it provided a roadmap for writing intellectual histories of Black youth politics that address how young people’s ideas about freedom and liberation change over time. Finally, it introduced scholars to the importance of studying the impact of Black Power in a local context.

When Woodard published his book in 1999, studies of the civil rights movement had largely declared that Black nationalism was the source of the Black Freedom Movement’s decline. However, Woodard pushed back against this declensionist narrative, arguing that “the politics of black cultural nationalism and the dynamics of the Modern Black Convention Movement were fundamental to the endurance of the Black Revolt from the 1960s into the 1970s.” (4) Furthermore, “Under [Amiri] Baraka’s leadership, elements of the Black Arts Movement and sections of the Black Power Movement merged to fashion the politics of black cultural nationalism in the Modern Black Convention Movement.” (1) Woodard suggested that the movement aided Black leadership development in several fundamental ways:

it created a forum for an ideological struggle over the direction of the Black Revolt; it was a political training ground for new leadership, offering workshops and plenary sessions where young people were exposed to new political perspectives; it nurtured in many local leaders a new identity in a national movement; and it created the political atmosphere for the development of black united fronts.” (84)

In no uncertain terms, Woodard outlined the intentional approach Black youth took in their struggles for self-determination and against structural inequality. In doing so, he produced one of the first studies to take seriously the intellectual and social contours of Black youths’ contributions to Black Power.

According to Woodard, Black Power and Black Arts activists launched the MBCM in 1966, with the Black Arts Convention in Detroit and the National Black Power conference-planning summit in Washington, D.C. At the 1967 Newark Black Power Conference, for example, civil rights and Black Power leaders such as Jesse Jackson and Maulana Karenga, and members from the National Urban League and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) met to discuss several issues that were pertinent to the Black community. These included Black economic development, political coalition building, and the urban crisis. Conference organizers coordinated workshops and plenaries that featured position papers on crucial political and economic issues. (86) The movement went on to produce four organizations: The Congress of African People (CAP), the African Liberation Support Committee (ALSC), the Black Women’s United Front (BWUF), and the National Black Assembly (NBA).

The struggles for power in electoral politics and public housing exemplified the impact and limitations of the Modern Black Convention Movement. For example, the NBA produced victories in mayoral elections, with Newark Mayor Kenneth Gibson’s win as the most prominent case. Additionally, Newark CAP developed its own community-based urban development project, Kawaida Towers, which was an apartment building that would house 200 families and would feature such amenities as a daycare center and a hobby shop. This project would serve as an alternative to the traditional urban renewal projects that displaced Black communities for business development. However, as Woodard masterfully shows, the story of the MBCM is not a celebratory history. We see this most forcefully in Mayor Gibson’s lukewarm support of CAP’s Kawaida Towers project despite the fact that it was the support of local Black communities that made his election possible. This betrayal marked the beginning of Baraka, and CAP’s, shift from Black nationalism to Marxism.

Although the MBCM revealed the limits of the “united front” approach to movement building, it remains a useful framework for making sense of the role of Black Power conferences in the leadership development of Black youth. Artist and scholar Michael Simanga’s experience as the founder of the Detroit CAP is an excellent example. At the age of 17 or 18 years old, Simanga earned the position of Secretary General of the Michigan Black Assembly in addition to leading the Community Organization Committee of the Detroit Chapter of the African Liberation Support Committee in 1972. However, when historians take a closer look at Simanga’s early adolescent years, we find that prior to organizing the Detroit CAP, he was one of the founding members of Detroit’s African-centered Ujima School. At the age of 16 years old, he was also one of the key strategists for the Mumford High School building takeover of 1971.1

Simanga’s relationship with Baraka and CAP illuminates the mutually beneficial relationship between Black youth and the MBCM. Although the activist found in Baraka additional inspiration to engage in the study of “international revolutionary thought, especially from Africa and the third world” and the opportunity to further develop his leadership skills, CAP gained in Simanga a young activist who had years of organizing experience in Detroit’s local communities.

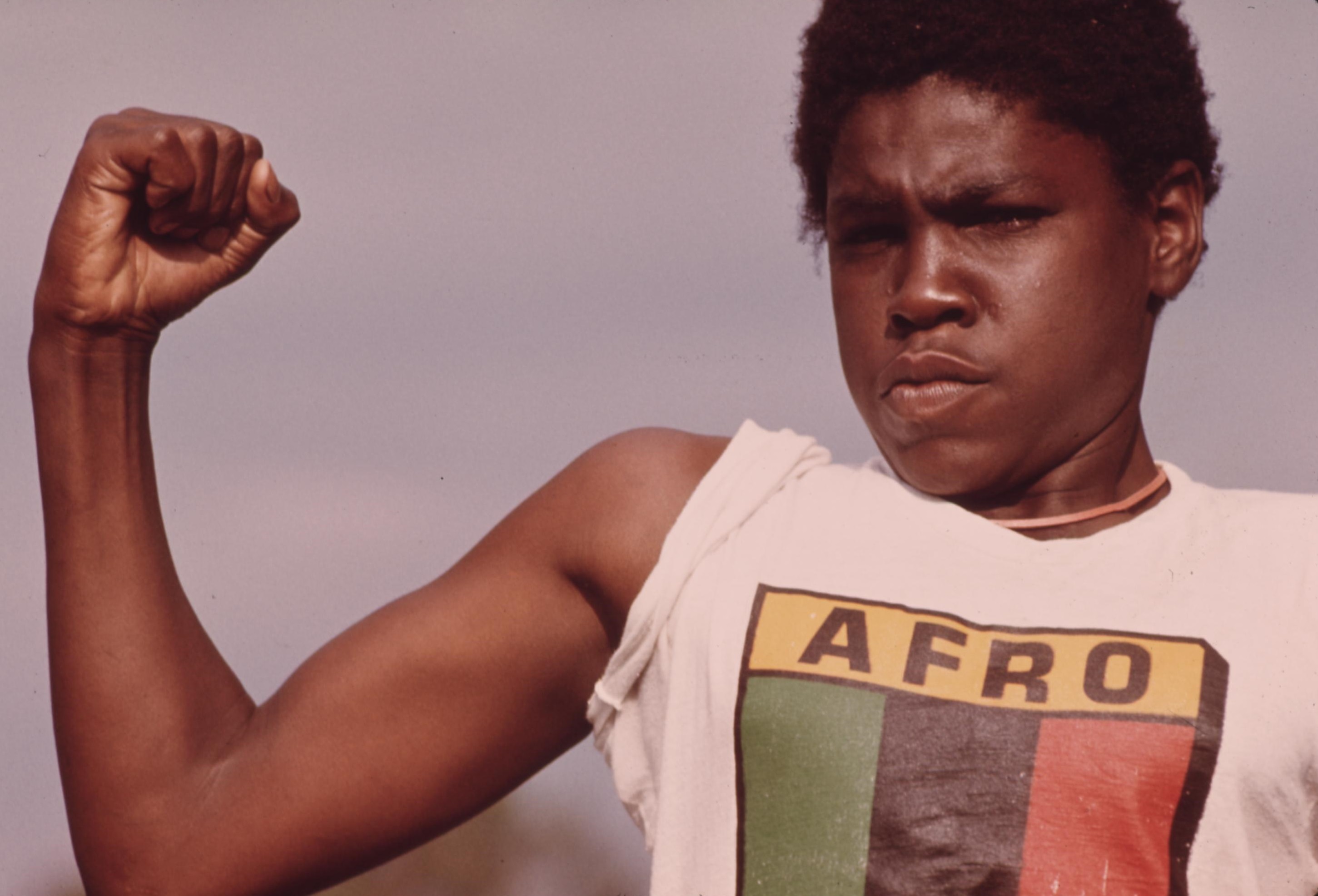

While Black youth found in the MBCM space to join the movement as leaders, they also likely gained the inspiration to organize independent national and regional Black youth conferences. In the fall of 1967, Black youth in L.A. held Black Youth Regional Conferences that sought to “’establish a national black communication system, create awareness and promote activity in the Western states, establish operational unit with inner city groups, and define and present new meaningful narratives as to how to cast off the oppression as imposed on black and oppressed people.” Two years later, youth affiliates of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers planned to organize a Black youth conference in Detroit that would take place the same week as the Black Economic Development Conference. These youth called for organizers and position papers, and invited speakers that would include: Dr. Nathan Hare, Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), Ron March of the League, and H. Rap Brown. The organizers proposed several workshops that aimed to explore: “Methods of organizing, building and maintaining a National Black Youth Organization and Voice, the Black Cultural revolution in the community and the schools.”2 In a political moment where Black youth shouldered the burden of police violence and racial inequality in schools, they sought to fight for liberation, collectively.

The twentieth anniversary of A Nation Within a Nation should prompt scholars to explore both the historical importance of the Modern Black Convention Movement in the development of Black youth leadership, and the possibilities and limitations such histories might reveal about this contemporary moment of youth activism. More pointedly, we should heed Woodard’s call to support the development of youth leadership by taking seriously histories of young people’s strategic approaches to social and political struggle.