The “Mock Revolution” at Mosinee: On The Racism of Anti-Communism in the US

For most of the last one hundred and fifty years, anti-communism has been a defining aspect of American political culture, both domestic and foreign. As historian Nick Fischer has argued, after the Civil War, anti-communism was deployed to suppress an unruly underclass of people, including the working poor, women, and Black Americans, and prevent any real attention on their working and living conditions. This anti-communism was deployed by an “elitist” class who sought to divide working people among themselves, and prescribe acceptable behaviors, including patriarchal heteronormative familial relationships. When those same people made demands for equal treatment, or even just decent treatment, the epithet “communist” or “socialist” has been deployed to delegitimize their claims to rights.

In America’s contemporary divisive political debates, communist and socialist are regularly hurled at those who attack the white male political structure. This is obvious in the treatment by both right-wing and moderate media of “the squad,” or the four Congresswomen of color — Rashida Tlaib, Ayanna Presley, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Ilhan Omar — who are regularly accused of having a communist or socialist agenda, when, at best, their programs reflect social democracy or a return to New Deal policies. Not only are the attacks by the president and his ilk on these women racist, but they are also nativist, as the president told them to “go back” to where they came from. This language is and has been deeply embedded in the racist history of American anti-communism, from both the right-wing and progressive forces in the United States, who have used communism and socialism as slurs to hinder real substantive progress in achieving racial, gender, and economic parity on the route toward equality.

The communist takeover of Mosinee, Wisconsin on April 20, 1950 exemplifies the racism at the heart of anti-communism. American anti-communists staged a 48-hour revolution to dramatize the perils of communism, but what it did instead was reveal the fears at the heart of American anti-communism, the fear of gender and race equality. The event was planned by the American Legion, with the help of two former communists, Benjamin Gitlow and Joseph Zach Kornfeder. During the coup, the mayor was publicly arrested, as were all religious leaders. They were herded into makeshift concentration camps while communist forces, played by American Legion members carrying unloaded weapons, secured the rest of the town. Mosinee’s one great industry in 1950, a paper mill, was shuddered, and the capitalist at the helm was arrested. Throughout the day the American Legion forces carried out summary arrests and occasional “executions” including of the police chief. Former communist turned anticommunist crusader, Benjamin Gitlow was named Commissar of the United Soviet States of America and made a speech at the local high school to the newly created Young Communist League. For 48 hours Mosinee was under “communist” control as a way to dramatize the elimination of liberties under communism. It was part of a larger movement spearheaded by the American Legion, to seize May Day from the left and celebrate May 1 as Loyalty Day. The revolution ended with the burning of all the communist material that was distributed, the raising of the American flag, and the mayor suffering a very real and very serious stroke while the remainder of liberated Mosinee celebrated at a bonfire. The Mayor died five days later, a minister who was also arrested, died May 7. The staged communist takeover was nevertheless declared a success.

The Wisconsin Communist Party and the National Communist Party noted that what Mosinee residents put on display was not the danger of a Soviet America, but what they really feared, racial integration and gender equality. The local Mosinee newspaper ran articles reflecting on the event in the days after. In one article Benjamin Gitlow, parroting old stereotypes about the intellectual weakness of women, warned that it was the average housewife who was most vulnerable to communist propaganda. But it was in the home where communism could be fought, the home where he presumed women ought to be. He warned not to be taken in by talk about peace; peace was a communist plot to weaken the United States for a Soviet takeover. Women, he feared were Soviet prey because of their vulnerability and had to remain diligent. The most poorly treated populations were believed to be the most susceptible to propaganda. Instead of encouraging better treatment, anti-communists warned others that change reeked of communism.1

After the takeover, the Daily Worker ran an article revealing that Mosinee had an “unwritten law” that prevented Black people from living within town limits or to remain overnight. The local paper mill, the primary industry of Mosinee and a large employer, would not hire Black people. The mill owner, E.P. Woodson, was linked to Masonite Corporation, a Mississippi business whose head was part of an anti-Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC) organization. Whether Mosinee had an unwritten rule that prevented Black residents is unclear, but in the 1950 census, the Black population of Mosinee stood at zero. The all-white Mosinee community revealed their true fears during the mock revolution, a change in the status quo that challenged their privilege.

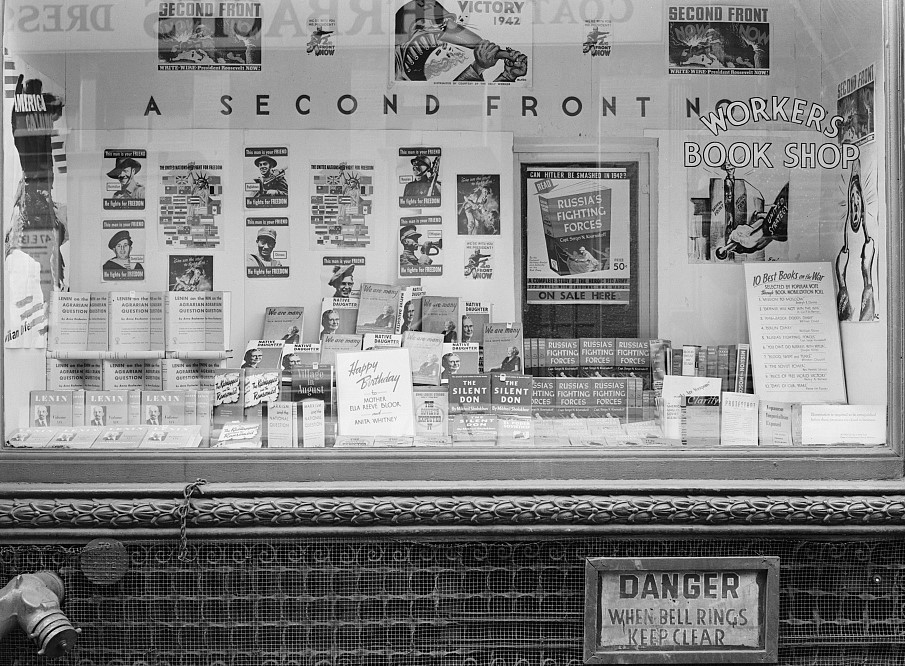

The Wisconsin Communist Party circulated leaflets in Mosinee that considered an alternative celebration for May Day, a day of union against capitalist interests that exploited workers and the racial and gender divisions that kept them divided. The pamphlet argued that the only thing capitalism offered Mosinee residents was low pay, poor conditions, and the perpetuation of Jim Crow policies. Capitalism, the pamphlet stated, only guaranteed Black oppression. It mentioned the bipartisan efforts to destroy the wartime FEPC, and the growing unemployment among Black workers. The communists noted that lynch violence in the South was only mirrored by police violence and brutality in the North, and housing discrimination, in places just like Mosinee, that prevented Black Americans from securing decent housing. Capitalist America could only offer Black Americans poverty, unemployment, violence, and discrimination. But white communities like Mosinee could guarantee their own success by capitulating to capitalist interests, accepting lower wages and poor conditions, in exchange for security in their own whiteness. The Party warned that capitalists made their wealth by shoring up white supremacy, and undermining labor conditions for all workers. 2

The Communist Party argued that if Mosinee residents really wanted to experience communism for a day, then it would be happy to send its own representatives to simulate it. But that simulation would include integration and equality, something the Mosinee residents did not appear interested in. The Party argued that what the mock revolution really mirrored were the fascist sentiments of Cold War policy that limited free speech and targeted dissidents. The “police state” during the mock revolution appeared to be much like the “witchhunt of 1950” that targeted Communist Party leaders and supporters and tried to make communism illegal.3

These “witchhunts” specifically targeted organizations and individuals that advocated racial or gender equality, solidifying the link between anti-communism and racist policy. Historians have argued that the anticommunist crusades that plagued 20th-century America linked anyone who advocated racial integration to communism in the eyes of a “segregationist public.” As civil rights figures like Paul Robeson, Claudia Jones, and W.E.B. Du Bois became critical of American foreign policy, the mainstream movement was forced to mute its criticisms. Those who refused became political pariahs and sacrificial lambs to the American intelligence apparatus. As Gerald Horne has argued, this “critical and radical perspective” was removed preventing the American left from becoming an important voice in criticizing American capitalism. The mainstream Civil Rights Movement could push for a Black American to eat at a lunch counter, but that same Black American might “lack the wherewithal to buy a hamburger.” Though these radical voices were muted, advocacy of anti-racism was seen as akin to communism and dismissed out of hand. Anti-communism allowed civil rights demands to be reduced to communist propaganda and gave a free pass to white America to ignore the plight of Black America.

These tensions were on full display in the Mosinee revolution, where an all-white town mocked the aspirations of those who sought equality and economic justice. This pageantry in Mosinee is one demonstration of the hostility toward civil rights and its criticism of capitalism. Obfuscating the intentions of communism and socialism has done real, long-lasting political damage to American political culture. Any program, no matter how moderate, to address poverty is painted as socialist, while actual corporate handouts are ignored and policies supporting corporate hording of wealth are celebrated. But worse, civil rights agitation has regularly been reduced to a terrorist threat, as evidenced by recently leaked information suggesting that the so-called Black Identity Movements garner more attention from federal intelligence agencies than white supremacist organizations who have employed terrorist tactics to murder hundreds of Americans. And civil rights goals are reduced to a communist plot to restrict the rights of white people, when the reality is that they threaten white supremacy. The American fear of communism has worked in tandem with racist policies as any attempt to emancipate Black Americans has been linked to communist agitation. This is the power of anti-communist policies that linger to this day, the fear that an “unruly underclass” will usurp the power and wealth of capitalists, and lay bare the inequalities inherent in American capitalism.

- Dorothy Parnell, “How to Avoid Falling into Communist Trap,” Benjamin Gitlow Papers, Box 5, Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University, Stanford, CA. ↩

- “For Peace, May Day 1950,” Benjamin Gitlow Papers, Box 5, Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University, Stanford, CA. ↩

- “Mosinee Also Wants Peace,” 2 May 1950, Daily Worker, p. 2. ↩

I am enlighten, again excellent coverage.

I would like an email address for you. Don’t have a twitter account.

At some point you might be interested in looking into Sarah E. Wright,

author of the classic novel This Child’s Gonna Live, celebrating the

50th anniversary of its original publication this year. A pioneering

work involving a unique kind of hero, field-working uneducated Black

woman in the Jim Crow South during the Great Depression. Ms. Wright,

while never a Party member was close friends with a number of Black

Communist leaders in the 1950s and thereafter. Was also an activist

in the African and African-American liberation movement.

If you would like further information you may reach me at

joekaye52831@aol.com. I was her husband of some 50 years.

Her papers are held at Emory University.

Thank you for this thoughtful analysis of a revealing episode in American history. I knew nothing about this incident at Mosinee until reading this piece, although as Dr. Lynn makes clear, it reflects a persistent, ongoing effort to discredit anti-racist efforts that continues today. I was struck by the timing of this piece, appearing the day after the New York Times posted its obituary of Jack O’Dell, whose contributions to the Civil Rights movement were curtailed by John F. Kennedy’s insistence that Martin Luther King, Junior purge “a Communist” from the SCLC. As disturbing as it is to hear the current right-wing attacks on, for example, Congressional Representatives Rashida Tlaib, Ayanna Presley, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Ilhan Omar, the reminder of Kennedy’s role in ending O’Dell’s activist contributions shows just how insidious this practice has been, on “both sides of the aisle.”