The Little Known History of Black Women Using Soda Fountains as Contested Spaces

The accurate accusation of tone-deafness has been circulating to frame the now-defunct Pepsi ad staring Kendall Jenner. For those who missed this commercial, in the ad, Jenner plays herself, initially involved in a professional photo shoot. As a crowd participating in a millennial-plentiful protest marches by (though what they are protesting against or for is never made clear), Jenner abandons her photo shoot and either has (what can be seen as) a social movement epiphany and decides to join the fray, or sees the marching millennials and wants to join what can be seen as an alternative photo shoot full of social media-friendly non-contracted photographers ready to upload her likeness to social media spaces such as Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook. It could be interpreted that Jenner sees the protest as an opportunity of viral proportions, to do as her sister Kim Kardashian did in the past while posing nude for Paper magazine, and “break the Internet.” Whatever her motivation, Jenner flings off her blonde wig, tossing it into the hands of a Black woman, grabs a Pepsi, makes her way to the front lines of the protest, and feels either courageous, comfortable, or protected enough to offer a white male officer an ice-cold cola beverage. The officer accepts the Pepsi, cracks it open, takes a swig, and smiles, and the protesters erupt in fist-pumping jubilation, high-fiving Jenner, and they all live (operative word is live) happily ever after, “bolder,” “louder,” and unharmed after an encounter with the police while protesting.

Later in the week Saturday Night Live satirically tackled the ad, lampooning it in a skit by highlighting the multiple absurdities that converged in the ad. During said skit, cast member Beck Bennett (playing the creator and director of the ill-fated commercial) believed that he was on the receiving end of a breakout opportunity to show the world how Pepsi can be the conduit for peace during protest. It is only minutes before filming the ad that he discovers friends, family, and even strangers are disturbed by his idea of paying “homage” to a protest movement based on an attack on systemic oppression suffered by Black people in America in order to sell Pepsi. During the skit, the accusation of being “tone-deaf” was used to describe Bennett’s character and subsequently his dream come true—his first commercial centered on the idea of a utopian protest possessing nearly perfect qualities and conditions for both protestors and police, while they are clashing in actualized dystopian-like conditions.

Again, while the ad was “tone-deaf,” the satirical nature in which the controversial commercial was criticized via the aforementioned SNL skit, credible outlets like the Washington Post, and the “hilarious” memes circulating on Twitter highlighting the obvious outlandishness of framing a soft drink as an elixir possessing the power to provide peace between protesters and police officers, a piece of history was lost—the history behind race, soda, and contested spaces. When I employ the idea of contested space(s), it should be understood as the physical public space(s) at the center of conflicting interests as defined by different social actors.

With Pepsi issuing a public apology and pulling the commercial, coupled with the rapid turnover of news stories and trending topics on social media sites, the Pepsi ad rests in a space of ephemerality and has been reduced to an ahistorical blunder of a cola company being “tone-deaf” to issues of race, particularly Blackness and civil unrest, and the optics of, as well as the historical narrative affixed to protester/police contact within public contested spaces. Even Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s daughter, Bernice King, sent a tweet within the moment, saying, “If daddy would have only known about the power of #Pepsi.” While MLK may not have “known about the power of #Pepsi,” he did know about the power of protesting cola companies—on the day before he was assassinated, Martin Luther King Jr. called for an economic boycott of Coca-Cola in Memphis, Tennessee due to their unjust employment practices within the Black community.

Though MLK may have been the highest-profile Black person to use soda as a site of protest, he was not the first to recognize the intersection between race, soda, and protest. For the remainder of this essay, we will engage with the under-explored intertwining of histories between race, protest, and soda, converging to create contested space(s). The contested space(s) that I am speaking of is the soda fountain, and how it became the locus of contestation for multi-generational struggles to end Jim Crow segregation in publicly accessible spaces.

Long before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama on December 1, 1955, and more than a decade before Martin Luther King, Jr. gave the historic “I Have A Dream” speech on August 28, 1963, during the March on Washington, there was a Black woman in Iowa beginning her own fight for the destabilization of Jim Crow segregation—and her name was Edna Griffin.

On July 7, 1948, Edna Griffin, John Bibbs, and Leonard Hudson stopped at Katz Drug Store in downtown Des Moines, Iowa. Griffin ordered an ice cream soda from the soda fountain and was promptly denied service due to the establishment not being “equipped to serve colored people.”

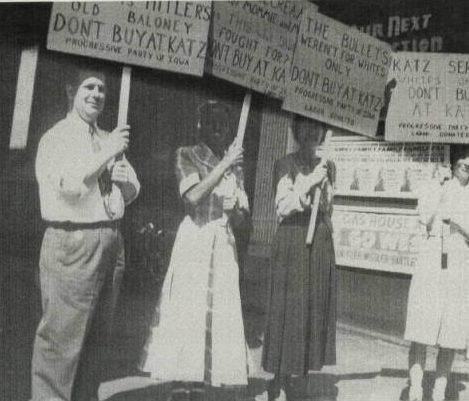

Griffin organized a boycott, conducted sit-ins, and picketed in front of the store every Saturday for two months, demanding an end to race-based refusal of service. The three filed charges against the store’s owner, Maurice Katz, in November 1948, citing violation of the 1884 Iowa Civil Rights Act prohibiting discrimination in a public place. During the criminal trial Katz was found guilty by a jury and was fined. Griffin then brought a civil suit for $10,000 in damages from the July 1948 incident against Katz. Edna Griffin’s civil case was heard and “an all-white jury sided with Griffin and awarded her $1 in damages, which her lawyer deemed a ‘moral victory.’” The landmark case ensured that soda fountains and restaurants in Des Moines had to serve Black folks by law, leading to the virtual elimination of legally upheld racial discrimination against Black people in public accommodations in Des Moines.

In July 1958, Carol Parks Hahn sat down at the popular local soda fountain at Dockum Drug Store in Wichita, Kansas. Like many other eateries throughout the country, Dockum Drug Store refused to serve Black folks at the counter. As Hahn recalls, “I ordered a coke, and then she [the waitress] came back, she notices others were coming in, and they sat down, and she looked at me, she leaned forward and said, ‘You’re not colored are you dear?’ And I said ‘Yes I am,'” and the waitress promptly refused to serve her. Starting July 19, 1958, Hahn (along with other young students) began entering the drugstore every day, filling the stools at the counter in front of the soda fountain, asking, “only that they be served a soft drink.” Every day for three weeks, the students alternated shifts of two to three hours occupying the counters, fully dedicated to a form of non-violent economic protest. On August 11, 1958 the owner of Dockum Drug Store relented, desegregating the counters at all nine of their locations, saying, “Serve them—I’m losing too much money.”

On August 19, 1958, Clara Mae Luper led thirteen youths (the youngest being six years old and the eldest being seventeen) into the Katz Drug Store in Oklahoma City, where they took seats at the counter, in front of the soda fountain, and attempted to order Coca-Colas. Denied service due to being Black, they refused to leave until closing time. They returned on Saturday mornings for several weeks. Although the Oklahoma City sit-ins only received local press coverage, they were the catalyst for the Katz chain to integrate its lunch counters and they effectively integrated every eating establishment in Oklahoma City.

What’s important to remember is that all of the aforementioned soda fountain sit-ins, from Des Moines, Iowa in 1948 to Oklahoma City, Oklahoma in 1958, predate the most well-known Civil Rights sit-in demonstration in American history, when on February 1, 1960, four North Carolina Agricultural & Technical University freshmen sat down at a Woolworth’s soda fountain in Greensboro, North Carolina. In addition to expanding on the timeline of sit-ins as a method of protest in a proactive effort to destabilize Jim Crow segregation, they also disturb the narrative of contested spaces in the fight to desegregate America’s public spaces as being an exclusively Southern phenomenon.

When considering the history of soda fountain sit-ins, particularly the Black women who were instrumental in organizing public protest and transforming formerly segregated leisure spaces into politicized contested spaces, along with how many of them have been under-recognized in the annals of Civil Rights Movement history, one can see how the Kendall Jenner Pepsi ad was not simply “tone-deaf.” The Pepsi commercial participates in the suppression of Black women’s roles in both historical and contemporary social movements, and by casting Jenner in the ad, this suppression is met with a culturally appropriated form of erasure that in many ways attempts to gentrify a generation’s place in a timeline of agency and agitation against systemic oppression.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.