The Life of Louis Fatio: American Slavery and Indigenous Sovereignty

In 1892 a reporter for the Missouri-based Daily Globe-Democrat interviewed an elderly Black man by the name of Louis Fatio living near Jacksonville, Florida. Throughout the interview, Fatio described parts of his tumultuous life of 92 years, first as an enslaved guide for the U.S. army and then as a captive living among the Seminoles. In sitting for the interview, Fatio seized an opportunity to recount his own version of his life story—a story that had been distorted and used by white Americans for various political purposes for decades.

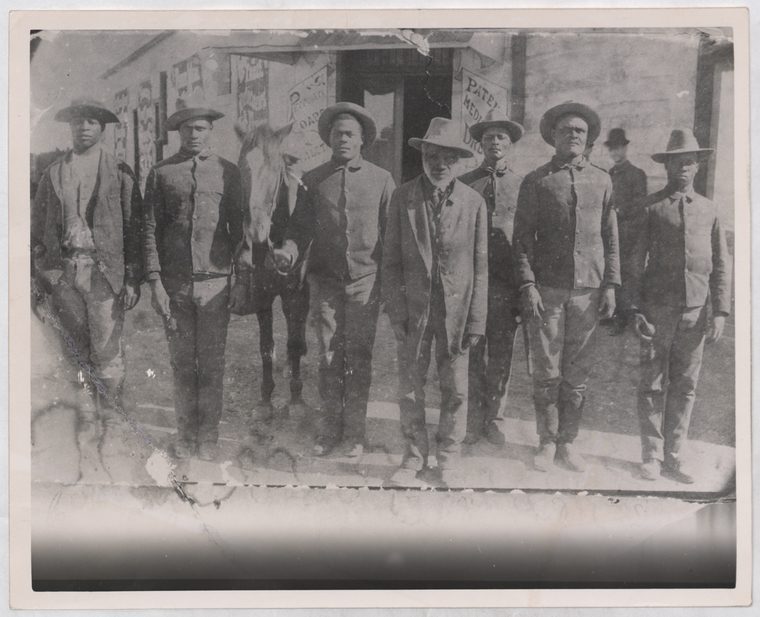

Fatio was born near Jacksonville, but he lived most of his life out West before returning to Florida around 1882. During an absence of nearly 50 years, Fatio had become relatively famous (or rather, infamous) throughout the country. In 1835 Seminole and Black Seminole warriors took Fatio prisoner after they massacred 110 United States soldiers, including Maj. Francis Dade (namesake of Miami-Dade County), for whom Fatio served as a guide. This massacre sparked the conflict known as the Second Seminole War, which lasted until 1842. Only one other person, Private Ransom Clarke, survived the attack. Fatio was initially presumed dead. It was later discovered, however, that Fatio had survived and was living among the Seminoles. From the 1830s into the 1870s, at least three white authors asserted that Fatio led Maj. Dade and his men into a trap. Fatio could not respond to this accusation because the U.S. let the Seminoles take him, along with several hundred other enslaved and free Black people, out of Florida and into Indian Territory in 1841. Fatio’s decades-long absence from Florida meant that it was white Americans who shaped his story and turned Fatio into a symbol that served different political goals on the issue of slavery. The 1892 newspaper interview allowed Fatio to seize control of his own story and directly alter the established history of the United States.

Fatio’s early life reflected the impact of Florida’s cosmopolitan population upon enslaved people. Fatio was born to enslaved parents in the year 1800 on the plantation of Swiss soldier and merchant Francis Phillip Fatio, called “New Switzerland,” which abutted the eastern bank of the St. John’s River. He grew up among Africans, Seminoles, Spanish, British, white, and African Americans as Florida changed hands between several nations before its eventual acquisition by the U.S. in 1819.

Susan L’Engle, Francis Fatio’s granddaughter, described Fatio as “remarkably intelligent and ambitious” just like his father, Adam—but that Fatio had a “roving disposition and hated restraint.”

Fatio’s life further illuminates the relationship between American slavery and Indigenous sovereignty that has been studied by historians such as Jane Landers, Barbara Krauthamer, and Alaina Roberts. The Seminoles’ refusal to respect American borders and property rights, particularly over enslaved people, ultimately led to war with the U.S. It also provided opportunities for enslaved people such as Fatio to exert their mobility and build relationships with different communities across multiple languages. Fatio’s desire for greater freedom and mobility was, L’Engle asserted, encouraged by the “free-and-easy roaming life” of the Seminoles who frequented the area. Furthermore, the Seminoles had stolen one of Fatio’s brothers as a child and raised one of Fatio’s sisters in their midst. Fatio thus had close kin among the Seminoles. According to L’Engle, Fatio picked up the Seminole language from his brother. Fatio made a name for himself in the area as a multilingual and educated enslaved man whose “knowledge of the Indian language made him almost invaluable.” He also married a freedwoman living in St. Augustine and frequently visited her for weeks at a time without permission. Eventually, a Cuban named Antonio Pacheco purchased Fatio and hired him out to several U.S. officers, including Maj. Francis Dade as an interpreter and guide.

An indemnity case brought to the U.S. Congress in 1842 cemented Fatio’s reputation as a willing participant in the massacre and revealed white Americans’ use of Fatio in whatever manner best suited their political purposes. It was John Lee Williams, a resident of St. Augustine, who first suggested in 1837 that Fatio had coordinated with the Seminoles, claiming that Louis “was frequently absent from the troops on the march; he fell on hearing the first gun, but directly after joined the enemy.” How Williams arrived at this conclusion is not known. It may be that Fatio’s Black Seminole siblings brought news to his wife and parents, or he was identified among the Seminoles. Fatio’s survival was officially confirmed in 1841 during negotiations between a Seminole leader named Coacoochee (called “White Cat” by white Americans) and U.S. General Thomas S. Jesup. Coacoochee brought Fatio along and claimed Fatio as his property by right of capture. Jesup agreed to let Coacoochee take Fatio with him, along with several hundred Black Seminoles, into present-day Oklahoma. Soon after Fatio’s removal, Antonio Pacheco’s heirs sought compensation from the U.S. government. The Pacheco family alleged that Maj. Gen. Jesup’s decision to allow Coacoochee to take Fatio into Indian Territory had robbed them of their slave and proper compensation for his loss. The Joint Committee on Claims (of which a majority of members were slaveholders) approved payment to Pacheco’s heirs.

Abolitionists in Congress used the case to launch attacks on the federal government’s direct financial support of slavery, with Fatio as an unwitting symbol for the abolitionist cause. In 1858, Representative Joshua R. Giddings of Ohio published a book on the Second Seminole War that portrayed Fatio as a heroic rebel against the U.S. slave power. Giddings excoriated U.S. slaveholders’ attempts to reclaim escaped enslaved people (or seek indemnities for their loss) who were living among the Seminole Indians in Florida precisely because it led to war. He depicted Fatio as a revolutionary who took “revenge for the oppression to which he was subjected.” In “sacrificing a regiment of white men, who were engaged in the support of slavery,” Giddings proclaimed that Fatio “asserted his own natural right to freedom…and made bloody war upon the enemies of liberty.” Thus, wrote Giddings, was the “life of this slave Louis…perhaps the most romantic of any man living.” Fatio the freedom fighter served a far more effective challenge to slavery than Fatio the unwilling war captive. Unable to tell his own version of the events from the fateful day in 1835 and all that followed, Fatio thus became an icon for both proslavery and anti-slavery arguments in the halls of U.S. Congress.

In his interview with the Daily Globe-Democrat, Fatio told his own story. Without Fatio’s account, he would have remained a symbol for others to use for their own purposes. Fatio framed himself as a victim of circumstance and outlined how, as an enslaved man, nations at war subjected him to their machinations over enslaved property. He asserted that he tried to warn Maj. Dade several times that the Seminoles might attack, which Dade simply “laughed” at and ignored to his peril. When the Seminoles took Fatio as a prisoner, he told them that “I wanted to go back to my people and that I was Spanish property.” The Seminole leader reportedly replied that Fatio was “enough American” for them, and he could not go back. Much as the Pacheco family laid claim to Fatio’s monetary value following his capture and removal to Indian Territory, the Seminoles laid claim to him as war booty.

By the time Fatio returned to Florida, the news of his survival and his version of the Dade massacre had reached Floridians, and it may be that he began to give interviews to ensure his return home would be peaceful. Fatio stated that he had received threats against his life as early as 1841. One can surmise from his multiple interviews that he at least anticipated some hostility. After “living for years and years among the Indians and wandering to and fro over the world,” Fatio wanted to come back to the land of his birth to be “among his own people and to lay his bones near where those of near and dear ones lie.”

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Fascinating!!

Thanks for this piece.

Amazing !