The Life of Betsey Stockton

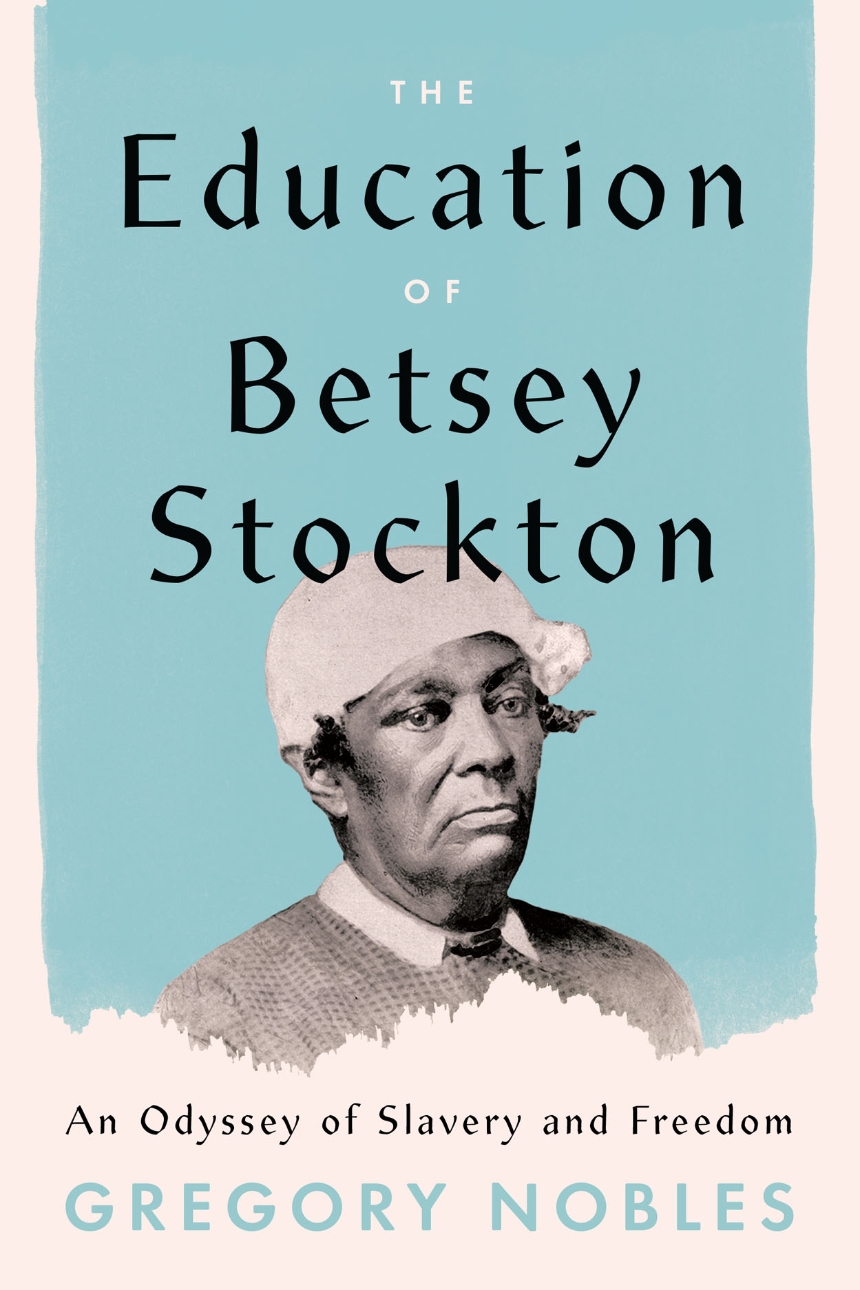

Gregory Nobles’s new book, The Education of Betsey Stockton: An Odyssey of Slavery and Freedom, is a tour de force. In this captivating work of biography, the author examines not only his subject’s life and passions but also the communities where she resided and the geographies she travelled. While Stockton’s archival record is relatively thin, Nobles creates a remarkably full picture of her and the world she inhabited. Each chapter provides a window into different social worlds, as we follow Stockton from her enslaved childhood and to her death as a free woman in 1865.

As a young girl, Stockton was given to the president of Princeton University, a presbyterian minister named Ashbel Green who was the son-in-law of Stockton’s first owner. Green would be one of the central figures in Stockton’s life. He emancipated her as a young adult and maintained a close albeit complicated relationship with her until his death. While born enslaved, Stockton devoted her life to teaching. She began her career as a missionary in recently “discovered” Hawai’i before running schools for Black children in Philadelphia and Princeton up until her death. Moreover, Nobles analyzes the influence of Princeton—town and university—on Stockton from birth to her death in 1865, making an able contribution to the study of slavery and universities. In every chapter, then, we learn not just about Stockton but also the institutions that influenced much of antebellum northern Black life.

Nobles also provides an excellent blue print for writing a scholarly biography of a person whose story is only partially captured by the archive. As the author puts it, “Trying to know Betsey Stockton on her own terms has involved the detective work of history, digging for shards of evidence from a variety of sources, exploring the physical environment and sensory experiences of her world, finding what other people wrote about her, occasionally reading against the grain of their belief and biases, trying to fill the empty spaces and silences in the archival record by judiciously engaging in some measure of historical speculation” (6). This is no work of historical fiction though, as Nobles makes explicit. Instead, he is adept at creatively using primary sources from correspondence among Stockton’s friends to contemporary accounts of the streets she walked.

The book comprises eight chapters plus a prologue and epilogue, with the first two chapters covering Stockton’s childhood up to her emancipation in 1817. By then, she was approximately nineteen years old. These chapters grapple with the complexities of slavery in the early republic and further reveal why Stockton is a such a rich figure for study. During this period, Stockton got into normal childhood hijinks, leading Green to deem her unruly and send her away for several years to a colleague in Philadelphia. In Philadelphia, Stockton became a keen student of Christian theology, a trait that would eventually earn her Green’s respect. Green, who owned Stockton during her childhood, was a reluctant slaveowner. Yet, either he or more likely a man from his wife’s family fathered Betsey Stockton with an unknown enslaved woman owned by Green’s in-laws. Green was also a colonizationist, representing many of the contradictions associated with the movement. The American Colonization Society had some roots in Princeton, seeming to mirror Green and the town’s dichotomous approach to the institution. Gradual emancipation occurred at a glacial pace in New Jersey. Likewise, Princeton residents and university students regularly debated slavery, yet both the town and university had a notoriously friendly relationship with slaveowners.

By virtually any standard, Stockton lived a remarkably mobile life, as is central to chapters three and four. In 1822, Stockton embarked on a mission to convert Hawaiian natives to Christianity. First though, Nobles spends an entire chapter analyzing her experience in route from the Northeast to Hawai‘i as a Black woman missionary. In the antebellum era, most with her complexion would be relegated to menial service rather than serving as a teacher. Upon arrival in Hawai’i, the racial dynamics only grew more complex. Her first reaction to the locals was shock at their scant clothing, describing them as appearing as “half man and half beast.” However, she confronted her own prejudice almost instantaneously, reminding herself that “They are men and have souls” (93). In Hawai’i, while Stockton met the local royalty, she spent much of her time teaching literacy and the bible to everyday people or the maka’āinana. While in service of a colonial project, Stockton’s desire to and skill in teaching everyday people shaped much of the rest of her life.

The next three chapters mostly relate to the prime years of Stockton’s life in the antebellum United States. Nobles recounts her teaching career in Philadelphia and then Princeton as well as her formative role in the founding of one of Princeton’s first Black churches. Once again, Stockton’s life provides critical insights into antebellum northern society. Black congregants founded the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church after white Presbyterians could no longer tolerate a unified church with segregated seating. Notable during this period, northern institutions began to practice systematized racial segregation. On the other hand, Stockton’s life also intersects with positive developments in the United States, notably the emergence of Northern states’ public education systems. Despite the segregation of education, Black children were not excluded. Stockton, moreover, played a critical role in cultivating a culture of literacy among Princeton’s Black residents. In 1855, Ann Maria Davison, a white Southern critic of slavery, toured Princeton’s Black community. Visiting many residences, she unknowingly found ample evidence of Stockton’s influence. “Madam,” a local resident explained to her, “you will not go into any of the houses of the colored people and not find pen and ink, or paper and pencil” (194). Books strewn about too; Davison found in the homes of families of more means. Stockton could not take all the credit by any means. Still, the city’s Black residents greatly benefitted from not only having a school but an experienced and exceptional teacher.

The book ends with an analysis of the Civil War’s impact on Stockton’s final years, and the educator’s enduring influence in Princeton since her death. Stockton lived to hear of the Confederate surrender, but perished just two months prior to the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in late 1865. Her home state of New Jersey would not ratify the amendment until January 1866, a further reminder of its long-standing sympathy with slaveowners. Many of the institutions that Stockton built endured well after her lifetime also, Nobles shows. For example, the great twentieth-century singer and activist Paul Robeson attended the school and church she helped build on Witherspoon Street. For a period, Robeson’s father even served as the Church’s pastor. Stockton, then, shaped the Princeton of her own life and generations afterwards.

Through his use of diverse print and archival sources, Nobles has created an impressive account of the life of Betsey Stockton. Outside of Stockton’s own published account of her work in Hawai’i, Nobles relies the writings of others like Green, her former enslaver, and the records of the schools and church where she taught. Additionally, he employs a wide range of contemporary accounts to describe the neighborhoods where Stockton lived and worked. This dynamic works to Nobles’s advantage, as the reader learns not only about Stockton but what it meant to be Black woman in the antebellum North.

In short, what Nobles delivers is the best that biography can offer. In The Education of Betsey Stockton, we learn about an important, pathbreaking figure and gain a better understanding of the world that shaped her and vice versa. From the end of slavery in the North to the creation of public education, Betsey Stockton’s life is an important window into a rapidly changing United States and how African Americans navigated it.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Thanks for this great book review… There are always surprises when we think that history only occurs in February. I had heard of her before in her connection with the mission to Hawaii … nice nice context and what we so like to call intersectionality…

I have been following the AMA (American Mission Association) and my fellow alum Samuel Chapman Armstrong and Hampton… Interactions with the Africans, Indigenous Folks elsewhere and the gospel… more food for thought and more reading. Going to be a good day! thanks again…

This is a very interesting review. I am interested in reading this book as I am writing the biography of a personality whose life trajectory has a striking similary. I believe the work of reconstructing the life of those slaves with little archives is a of great values.

When the governor of Florida ludicrously asserted last year that slavery “benefited” the enslaved by allowing them to acquire useful skills, he cited the example of Betsey Stockton. Greg Nobles wrote a response that was published in the Atlanta Journal Constitution, which includes the following “correction” to the Florida African American History guidelines:

“Even as a free woman of color, [Betsey Stockton] could never ignore or escape the pervasive racism of American society, in the North as well as the South, and particularly in Princeton, at a time when the College of New Jersey actively recruited students from below the Mason-Dixon Line.

Beneath the genteel veneer of this small college town simmered an ugly underside of anti-Black prejudice, at times even outright violence. Being the one Black teacher in such a town could never be easy, but she worked at it day after day, year after year, until the day she died. Given her circumstances, Betsey Stockton stands as a success, an imposing pillar of the Black community in Princeton, where she is still remembered and revered. But to portray her success as an extension, much less a benefit, of her enslavement is to tear her out of her historical context, to embrace a benign-seeming view of the vicious institution that left its mark on her from birth, as it did so many other Black people of her era.

And yes, like Betsey Stockton, other people born into slavery did use their initiative to make their own mark on society. They were human beings, after all, with intellect and imagination, not mindless automatons merely doing rote labor. But whatever they achieved pays credit to their own effort, not to their enslavement.

To suggest, as the Florida guidelines do, that slavery could have been a springboard to success is a cynical attempt to emphasize particular individuals to sanitize a pernicious institution.”