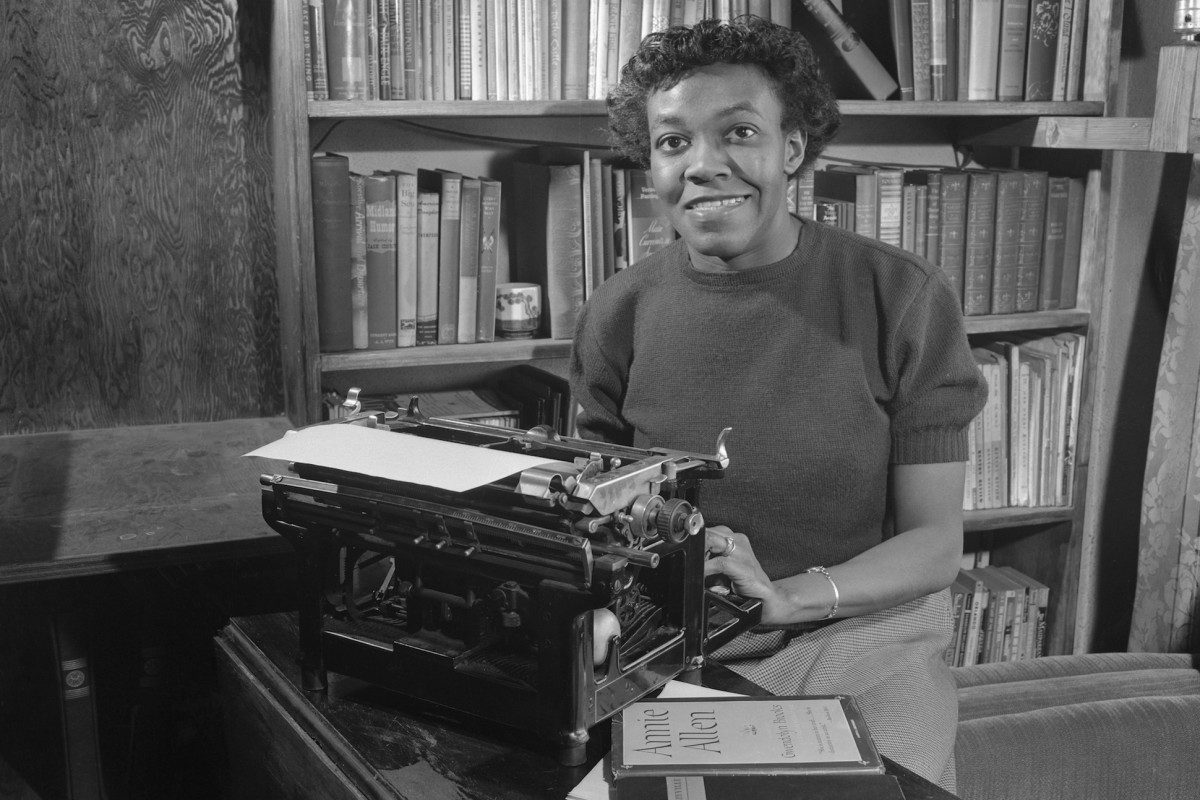

The Life and Legacy of Gwendolyn Brooks

With this past June marking the 100th anniversary of Gwendolyn Brooks’s birth, it is important that we reflect on the life and work of a woman who was truly ahead of her time. In the words of novelist Richard Wright, “America needs a voice like hers.” And what better way to celebrate her life than to spotlight her life and legacy through a brilliant biography?

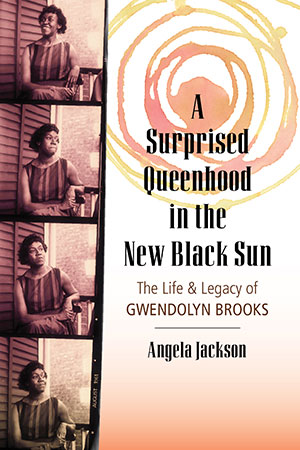

In A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun: The Life and Legacy of Gwendolyn Brooks, Angela Jackson–an award-winning poet, playwright, novelist, and fellow Chicago resident–takes up this significant task. With access to a wide array of sources, including oral histories from Brooks’s family members, Brooks’s personal papers, and her public writings, Jackson maps out Brooks’s long literary life and career–all while drawing attention to the creative methods of her artistic talents.

Prior to Jackson’s A Surprised Queenhood, Gwendolyn Brooks’s story has been told through compiled groups of selected poems honoring her gifts and talents or examining her writing process.1 And although Brooks’s longtime friend and literary associate, George E. Kent, published the first full-scale biography of Gwendolyn Brooks in 1993, Jackson offers a more intimate homage to Gwendolyn in such a way that is reminiscent of a student carrying the torch of their mentor.

A Surprised Queenhood is more than just a sharing of key moments and memories, but a book that lovingly shares the exceptional life and work of Gwendolyn Brooks. Many of these moments, such as her participation in the NAACP Youth Council, foreshadowed her progressive thinking and life as an activist. These moments also included her leadership and literary commitment to the South Side Writers Group, which contributed significantly to her intellectual development. Additionally, as Brooks soaked in her own success as a poet laureate, she would pay it forward in her teaching and giving back to the Black community. Her giving consisted of sending Black writers to Africa for enrichment, donating monies for literary prizes to students at various Chicago Public schools, giving prize money to the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) writers’ workshop poetry contest, and initiating the Gwendolyn Brooks Literary Awards. This generosity became routine for Brooks and would continue even after her passing.

A Surprised Queenhood is more than just a sharing of key moments and memories, but a book that lovingly shares the exceptional life and work of Gwendolyn Brooks. Many of these moments, such as her participation in the NAACP Youth Council, foreshadowed her progressive thinking and life as an activist. These moments also included her leadership and literary commitment to the South Side Writers Group, which contributed significantly to her intellectual development. Additionally, as Brooks soaked in her own success as a poet laureate, she would pay it forward in her teaching and giving back to the Black community. Her giving consisted of sending Black writers to Africa for enrichment, donating monies for literary prizes to students at various Chicago Public schools, giving prize money to the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) writers’ workshop poetry contest, and initiating the Gwendolyn Brooks Literary Awards. This generosity became routine for Brooks and would continue even after her passing.

In A Surprised Queenhood, we are able to take a journey into Brooks’s writing and her innermost life–whether it be her teen years, motherhood, or her later life as an activist. Significantly, the biography not only sheds light on Brooks’s life and legacy, but it also offers a glimpse into Black life in Chicago during the twentieth century. Each chapter explores how Brooks became a key figure in contributing to the landscape of the Bronzeville-Chicago area as a space for another Black Renaissance.

Beginning at the early age of 11, Brooks embarked on her career as a poet who would eventually become an award-winning and highly regarded literary figure. With aspirations to publish, and heavily influenced by the well-known Chicago Defender newspaper, Gwendolyn was destined to share her gift of poetry to the world–so much so that her mother made the prediction of saying Gwendolyn was going “to be the lady Paul Laurence Dunbar.” And fortunately, Jackson provides readers an opportunity to read her work, while simultaneously learning the evolution of each piece and its connection to Brooks’s life.

For Brooks, poetry was a response to her experiences, whether it was personal slights and insults from her elementary school classmates (“Forgive and Forget”), to expressing her opinion on the role and purpose of Black poets (“Poets Who Are Negroes”), or giving courage and strength to the youth of Soweto, South Africa fighting against uprisings (“The Near-Johannesburg Boy”). Inspired and mentored by such literary figures as Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, and Richard Wright, Brooks also implemented work/life mantra of self through self-acceptance, self-love, and self-confidence. With each year, Brooks’s poetry was elevated, transformed and revolutionized. Jackson talks about this growth and how it would be triggered while attending the ‘Visionaries Workshop’ at the Fisk Writers Conference in 1967. From this experience, we learn that not only does Gwendolyn’s writing evolve, but her relationships and friendships took flight as well.

While Jackson’s book unquestionably features Brooks’ poetry and literary life, it also speaks to her life as an activist. When talking about Brooks we tend to only focus on her literary contributions and impact in and outside of Bronzeville. However, there is racial pride–as Brooks would say, a “beauty of Negroness”–which mirrored that of Chicago’s neighboring cultural movement the Harlem Renaissance. Jackson highlights how Brooks is more than just a poet but a “committed race woman,” and as a race woman, issues of Black housing and racial injustice against Black people became central themes in Brooks’s poetry. This is seen early in her active commitment and involvement with the NAACP Youth Council particularly around the issue of lynching (“The Ballad of Pearl May Lee”). Where most people associate the anti-lynching campaign primarily with Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Brooks also offered her talent as a poet to this cause. She focused on lynching as well as offered her words in relation to the murders of Emmett Till, Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X. Brooks had an honest reaction to such things as Black life and culture, music, and the war. All the while, never forgetting her lifelong connection to the Black Metropolis-Bronzeville area.

As a Black woman poet-activist, Brooks also exemplified what it meant to balance womanhood, motherhood, and art. Jackson, as a poet herself, crowns Brooks into “queenhood” in a way that also channels a Black feminist approach to her life and work. Through Brooks’s life and work, Jackson shares the many layered emotions that a Black woman might embody in a racist society. In the early chapters, we learn of Brooks’s desire to experience motherhood, much like how her mother, Keziah Brooks, did for her and brother Raymond. Jackson also reveals the many voices of womanhood and motherhood and how essential these experiences were to Brooks– even if it meant traumatic moments.

Disclosing sensitive moments deftly and with respect is a trait that works well for Jackson as she allows readers to gain a clear view of Brooks’s home, personal, social, and activist life. This is particularly shown through both the moments of struggle and happiness within Brooks’ marriage to her husband, Herbert Blakely. This honesty is further exemplified through a bold poetry move. In the chapter titled “Visionaries,” Jackson shares with us the courage and strength that Brooks embodies through her poem “The Mother” as she tackles the controversial subject of abortion. This poem had such an impact that when asked to evaluate Brooks’s full volume of poems, later to be called A Street in Bronzeville, fellow poet and novelist Richard Wright praised her poems as a whole but would object to the inclusion of “The Mother.” Despite Wright feeling that there was no poet who could tackle the subject of abortion in poetry, Brooks was adamant to keep the poem in the volume. Her choice to keep this poem beautifully captures the raw emotions of a woman—regret, sorrow, loss, guilt. Such an undertaking in 1945 was not only illegal, but even more of a revolutionary act to write about publicly. This act of liberation is part of the transparent viewing of Brooks that Jackson articulates throughout the entire book.

In A Surprised Queenhood, Angela Jackson carefully unpacks Brooks’s work and life so that long-time admirers can continue to appreciate her legacy, while newcomers can discover her determination and bravery as a literary giant who blazed a trail for other poets and authors. Readers can see the blending of details in Brooks’s life with critical views and significant shifts of content and form in her poetry. As a budding scholar-activist and an admirer of Brooks’s poetry and activism, I find inspiration in her story—and no doubt readers will be equally inspired. Through the combination of Jackson’s incisive analysis and Brooks’s own poetry and prose, we learn that Gwendolyn Brooks was not only a literary giant—she was a teacher and student of her craft, constantly pushing boundaries and giving voice to those unable to tell their own stories.

- These works include Peter Kahn, Ravi Shankar, and Patricia Smith (eds.), The Golden Shovel Anthology: New Poems Honoring Gwendolyn Brooks, (Pine Bluff: University of Arkansas Press, 2017); Gloria Wade Gayles (ed.), Conversations with Gwendolyn Brooks, (Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2003); Maria K. Mootry and Gary Smith (eds.), A Life Distilled: Gwendolyn Brook, Her Poetry and Fiction, (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1989); D.H. Melhem, Gwendolyn Brooks: Poetry and the Heroic Voice, (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1988). ↩