The Lasting Legacy of Black Marxism

This is the second day of our roundtable on Cedric Robinson’s book, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. We began with introductory remarks by Paul Hébert on Monday. In this post, historian Joshua Guild traces the influence and inherent challenge within Cedric Robinson’s vision of the Black radical tradition.

Joshua Guild is an Associate Professor of History and African American Studies at Princeton University. He specializes in twentieth-century African American social and cultural history, urban history, and the making of the modern African diaspora, with particular interests in migration, black internationalism, black popular music, and the Black radical tradition. Guild is currently completing his first book, In the Shadows of the Metropolis: Cultural Politics and Black Communities in Postwar New York and London, which will be published by Oxford University Press. The book examines African-American and Afro-Caribbean migration and community formation in central Brooklyn and west London from the 1930s through the 1970s. His chapter, “To Make That Someday Come: Shirley Chisholm’s Radical Politics of Possibility,” appeared in Want to Start a Revolution?: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle, edited by Dayo F. Gore, Jeanne Theoharis, and Komozi Woodard. He edits the Medium series Focus. Follow him on Twitter @jbguild.

Joshua Guild is an Associate Professor of History and African American Studies at Princeton University. He specializes in twentieth-century African American social and cultural history, urban history, and the making of the modern African diaspora, with particular interests in migration, black internationalism, black popular music, and the Black radical tradition. Guild is currently completing his first book, In the Shadows of the Metropolis: Cultural Politics and Black Communities in Postwar New York and London, which will be published by Oxford University Press. The book examines African-American and Afro-Caribbean migration and community formation in central Brooklyn and west London from the 1930s through the 1970s. His chapter, “To Make That Someday Come: Shirley Chisholm’s Radical Politics of Possibility,” appeared in Want to Start a Revolution?: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle, edited by Dayo F. Gore, Jeanne Theoharis, and Komozi Woodard. He edits the Medium series Focus. Follow him on Twitter @jbguild.

“To define our liberation in terms of a canon or the multiculturalization of knowledge therefore simply serves to continue our ongoing destruction as a population group. ‘It’s the Black ones that are dying,’ as Sistah Souljah pointed out. Their death is the ‘price of our ticket,’ our canon, our treason as intellectuals…We cannot as a population group of African descent, wholly or partly, expect any other result but our continued degradation and global disempowerment, within the terms of our present conception of the human, Man, and the order of knowledge by means of which this conception is elaborated.”–Sylvia Wynter, “A Black Studies Manifesto” Forum N.H.I.: Knowledge for the 21st Century (Fall 1994)

“As a scholar, it was never my purpose to exhaust a subject, only to suggest that it was there.”–Cedric Robinson, preface to the 2000 edition of Black Marxism

Black Marxism is not a book one reads once and casually sets aside. On the contrary, it insists on being revisited, wrestled with, and argued over multiple times. Transcending disciplinary boundaries and overflowing with analytical provocations, it is a book that is best picked up not in scholarly solitude but in dialogue with others—with comrades, fellow students, or reading group co-conspirators. Cedric Robinson’s exceedingly humble retrospective disclaimer notwithstanding (“it was never my purpose to exhaust a subject”), one is struck, above all, by Black Marxism’s remarkable ambition. As many have noted, Robinson’s audacity is rather masked by the book’s title, whose powerful simplicity fails to adequately convey the sweep of its argument, the capaciousness of its archive, or the range of its bibliography.

The book’s reach and breadth is a kind of double-edged sword. They are the blade that Robinson wields so deftly, opening up huge swaths of intellectual terrain in order to reconceptualize the very origins of Western modernity and the concomitant genealogies of resistance to racial capitalism and its logics of subjugation. Black Marxism proffers nothing less than the kind of transformative re-ordering of knowledge called for by Sylvia Wynter. Yet it is the book’s very scope that makes it so daunting to the uninitiated and challenging even to the reader familiar with the broad outlines of story it seeks to narrate.

For these reasons, Black Marxism is a difficult book to teach. I’ve found that even the sharpest graduate students often struggle to find their way into the text, to gain their footing and orient themselves to its core aims. To be sure, students encountering the text nowadays are most likely to read the 2000 University of North Carolina Press reprint edition, featuring a new preface by Robinson and Robin D.G. Kelley’s indispensable foreword. This edition appeared during my first year of grad school and was my introduction to Cedric Robinson and his masterwork. Yet even with the benefit of this invaluable prefatory material illuminating context and intellectual lineages, I recall being confounded by the text’s magnitude and the way it ranges from the ancient world to the rise of the Western bourgeoisie through to the twentieth century writings of W.E.B. Du Bois, C.L.R. James, and Richard Wright (the latter a writer whom I at least thought I knew). I am not ashamed to admit that I had difficulty seeing the forest for the trees.

For these reasons, Black Marxism is a difficult book to teach. I’ve found that even the sharpest graduate students often struggle to find their way into the text, to gain their footing and orient themselves to its core aims. To be sure, students encountering the text nowadays are most likely to read the 2000 University of North Carolina Press reprint edition, featuring a new preface by Robinson and Robin D.G. Kelley’s indispensable foreword. This edition appeared during my first year of grad school and was my introduction to Cedric Robinson and his masterwork. Yet even with the benefit of this invaluable prefatory material illuminating context and intellectual lineages, I recall being confounded by the text’s magnitude and the way it ranges from the ancient world to the rise of the Western bourgeoisie through to the twentieth century writings of W.E.B. Du Bois, C.L.R. James, and Richard Wright (the latter a writer whom I at least thought I knew). I am not ashamed to admit that I had difficulty seeing the forest for the trees.

I took some solace in the knowledge that I was not alone. In his foreword, Kelley recounts his own first encounter with Black Marxism while in graduate school at UCLA in the 1980s. Assigned to review the book for a student journal, Kelley confesses to being so daunted by the text that he had to set it aside. “I finally completed my first reading of Black Marxism about two months after I took it home. The book so overwhelmed me that I suffered a crisis of confidence,” he writes (xv). But like Kelley and, I suspect, legions of other readers, my persistence was rewarded.

Kelley goes on to call attention to the relative critical silence surrounding the book upon its publication in 1983, noting the paucity of substantive reviews in either academic journals or more popular media outlets. Indeed, one of the few extended reviews of Black Marxism didn’t appear until five years after the book’s initial publication. Writing in the socialist magazine Monthly Review, Cornel West lauded Black Marxism while taking issue with key aspects of Robinson’s method and analysis. West declares:

Robinson’s book is a towering achievement. There is simply nothing like it in the history of black radical thought. It is, in many ways, too ambitious. Yet in trying to do too much, Robinson raises the most fundamental questions facing both the black and white Left in America: to what extent are Marxist explanations of social history capable of grasping the many dimensions of racial oppression? What is and ought to be the relation of black resistance to broader working class insurgency? What is distinctive about dominant forms of black radicalism in contrast to non-black forms? How ought black left intellectuals relate to Marxist traditions?1

In suggesting that Robinson tries “to do too much,” West points to a central paradox of the book. If the text struggles at times to bear the full weight of its ambitions, one wonders if it could actually be any other way. Could a book of more modest conception both account for the failings of Western Marxism and trace an alternative history of resistance with any satisfaction? Put differently, do not Robinson’s animating concerns regarding the longue durée of black liberation demand engagement on an epic scale?

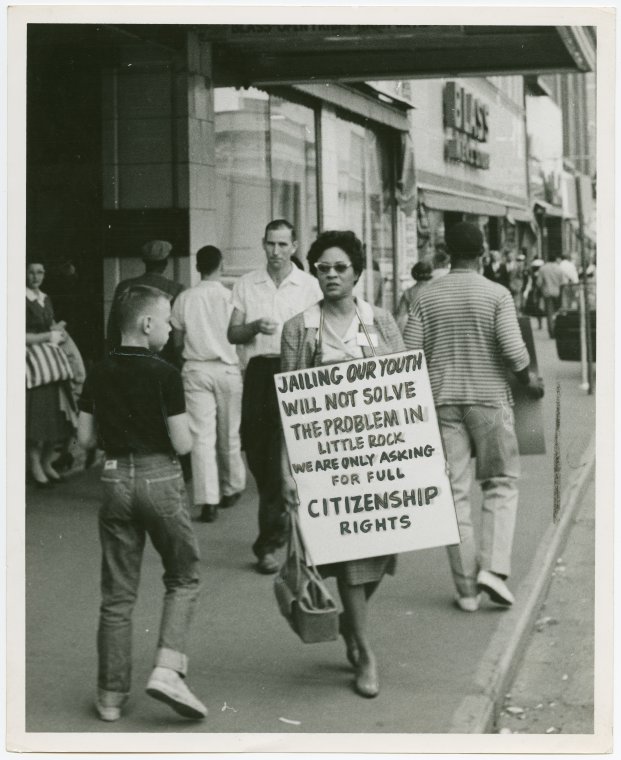

Perhaps Black Marxism’s greatest gift is the way Robinson casts an expansive Black radical tradition so as to help us imagine a radical future. In not simply asserting but, instead, carefully reconstructing a centuries-long “tradition” of radical thought and action, Robinson challenges a range of orthodoxies—from conventional Marxism to nationalism—regarding the wellsprings and contours of (black) resistance. Historical excavation, the book argues, is a necessary prerequisite to cultivating black radical imaginaries.

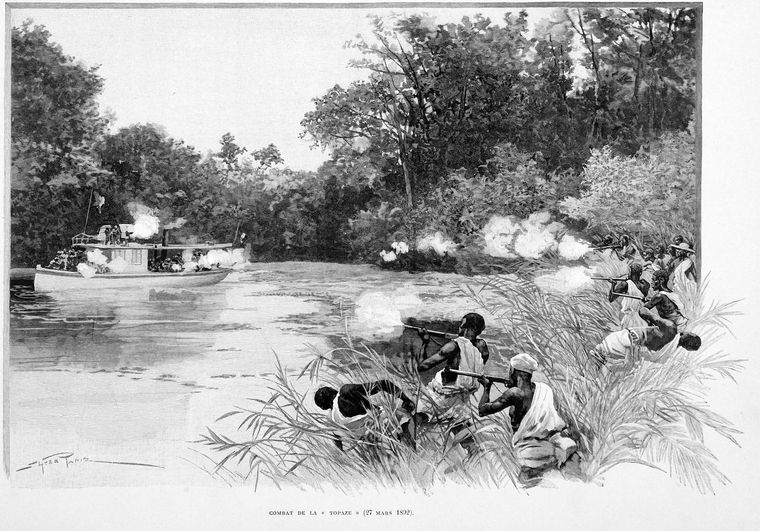

Black Marxism advances an argument that history contains if not a blueprint than a series of torchlights for revolutionary struggle. Robinson writes, “In the twentieth century, when Black radical thinkers had acquired new habits of thought in keeping, some of them supposed, with the new conditions of their people, their task eventually became the revelation of the older tradition. Not surprisingly, they would discover it first in their history, and finally all around them” (p. 170). The work of charting a new course forward, Robinson suggests, begins with a critical appraisal of and appreciation for the past.

Alongside its groundbreaking analytical framework and host of thought-provoking interpretations, a return to Black Marxism also raises some vexing questions. Chief among these is: Where do we locate women, as both thinkers and as historical actors, in this Black radical tradition? We’re left to speculate, for example, about what it would mean for a figure like Claudia Jones, who theorized the complicated interplay of gender with race and class in the context of her evolving Marxism, to be properly situated in the ranks of the “renegade intelligentsia” alongside her ostensible contemporaries Du Bois, James, and Wright.

But more than being simply a matter of “inclusion,” we have to ask how a gendered analysis of enslavement and colonialism—and the economic, political, and social orders that followed in their wake—rearranges the picture and alters the conclusions drawn. What does the long trajectory of black labor and class formation—and, by extension, radicalism—look like when we center gender? Thankfully, we have at least three generations of scholarship informed by black feminism to begin to answer these questions, to supplement and revise Robinson’s template.

“It is almost always impossible to say when and where a movement will arise,” writes Keeanga-Yahmatta Taylor, “but its eventual emergence is almost always predictable.”2 More than three decades ago, Cedric Robinson bequeathed to us a kind of almanac of radical struggle. While Robinson refrained from making scientific predictions about the future, his book nonetheless offers a bold new way of reading the past intended to equip us, his readers, with tools to foresee a new world coming and the paths that might be taken to get there collectively. “The resoluteness of the Black radical tradition,” Robinson concludes, “advances as each generation assembles the data of its experience to an ideology of liberation.” That tradition, he argues, increasingly “adhere[s] to its own authority,” no long reliant on models of change theorized out of the conditions of others (p. 317). In this current tumultuous moment, we would be wise to sit in dialogue once again with this landmark book.

Josh —

Thank you so much for this great look at Black Marxism.

I’m especially curious about your experience teaching the book. I read it on an exam list in grad school, and never really had the chance to wrestle with it in the collaborative setting of a seminar. I would love to know more about how students — especially students who are not necessarily specialists in the history of Black radicalism/Black intellectual history/anti-colonial thought — react to Robinson’s complete re-framing of the narrative of “Western civilization.” I think because I had read enough Eric Williams and CLR James early on in my intellectual development, I was a little more ready to accept the terms of Robinson’s argument — but what are the experiences of students who have never engaged with the tradition that Robinson is rooted in?