The Historical Significance of Black Queer Films

In the context of the reemergence of Black nationalist rhetoric and ideologies in hip-hop music in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Ice Cube released his album Death Certificate in 1991. Among the track list is a song entitled “Horny Lil Devil.” Cube spends most of the second verse associating homosexuality with whiteness and marking its subordinate status. Cube suggests that non-heterosexual Black people could not assume an authentic role within the community. According to Cube’s lyrics, “true n—– ain’t gay.”At the same time that Cube’s album exposes and calls into question the violent history of white supremacy, he also fuels homophobia and the exclusion of Black queer folks from the liberation that he argues that all (heterosexual) Black people deserve. As scholar Charise Cheney explains, 1980s and 1990s hip-hop artists, including those within the conscious hip-hop movement like Chuck D and KRS-One, in addition to so-called “gangster rappers” like Ice Cube, embraced the rhetoric of Black nationalism and viewed themselves as building on the legacy of their “forefathers” in a masculinist genealogy of Black Power. In a range of tracks, Black artists sought to influence, empower, and educate Black communities in relation to white supremacy; at the same time, the music centered the empowerment of heterosexual Black men often negating the blackness of Black queer communities altogether.

Responding in the context, Angela Davis wrote her 1992 essay, “Black Nationalism: The Sixties and the Nineties,” raising a challenge to the reemergence of popular forms of sexist and heterosexist Black nationalist ideology or what she termed, “narrow nationalism.” In the same era, other Black queer thinkers interrogated narrow nationalism through film. For example, while addressing the stringent boundaries of Blackness and perpetuation of heteronormativity in Black communities in particular, Marlon Riggs’s Black is, Black Ain’t (1994) and Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman (1996) critiqued the homophobic rhetoric that further marginalized Black LGBT folks and excluded them from visions of Black liberation. In particular, Riggs and Dunye provided nuanced perspectives on Black LGBT communities’ positionality and experiences within Black communities. Both films centered the experiences of Black queer people not only to communicate how Black LGBT folks endured further marginalization within Black communities because of their queerness but also to interrogate the ways that the conflation of queerness and whiteness attempted to exclude Black queers from the bonds and protection of community.

Taken together, these films examined Black LGBT folks’ experiences with intra-racial antagonism and homophobia. They challenged the perpetuation of a politics that privileged some and excluded others pointing to the ways that it reinforced the social structures of white supremacy that Black nationalist rhetoric ostensibly aimed to dismantle. Riggs’ and Dunye’s interrogation of heteronormativity in Black communities illustrates their use of film to depict a form of what José Esteban Muñoz has described as (dis)identifcatory politics, understood as the act of critiquing the rigidity of identity categories while also engaging them in order to access community and combat systemic oppression collectively.

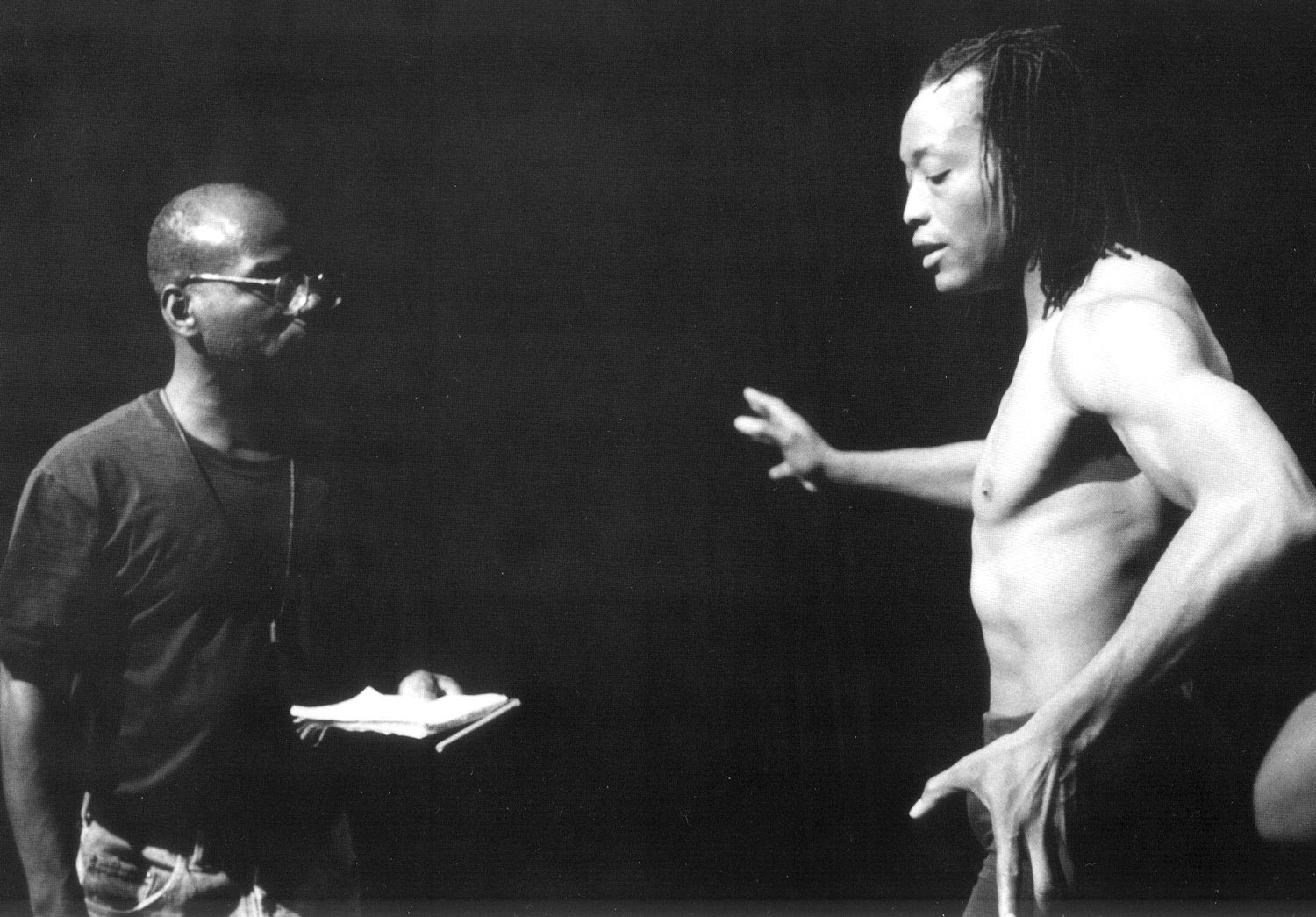

In his 1996 documentary, Black Is, Black Ain’t, Marlon Riggs interrogates the perpetuation of monolithic understandings of blackness within Black communities that delimit the possibilities of how blackness can be embodied. Throughout the film, Riggs engages Black intellectuals, thinkers, and artists, who experienced ostracization due to demarcations of queerness as beyond the boundaries of blackness. At the outset of the film, Riggs presents gumbo as a metaphor for the variance in embodied and experiential Blackness. This vision of blackness as a complex and non-uniform stew sets up his challenge to the absurdity of Black essentialism and the marginalization of Black LGBT folks, which are the subjects of the rest of the documentary. Barbara Smith’s and Essex Hemphill’s commentary along with “Portrait of Jason” performed by poet Cheryl Clarke, illuminate how Blackness was often equated with maleness and heterosexuality in the context of the “narrow nationalism” Davis’s essay described. Hemphill speaks, along with Smith, about how his queerness was used in an attempt to negate his Blackness and how homosexuality was seen as “the final break in Black masculinity.” Like Davis, Riggs connects the violence of narrow nationalism to the erasure of the significant contributions of queers in the context of the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements. Specifically, he draws attention to Bayard Rustin, who was responsible for the organization of the March on Washington in 1963. Riggs uses Rustin’s marginality in his own era and his suppression in popular memory as an indicator of how heteronormative Black political ideology preserved conservative constructions of Blackness that helped to entrench white supremacy as well as sexism and heteronormativity.

The portrayal of Rustin’s invisibility and marginalization, coupled with Smith and Hemphill’s commentary, directly indicts the mobilization of what Cathy Cohen describes as a single-oppression framework. A single-oppression framework, according to Cohen, not only perpetuates essentialism but reifies the same power structures Black political ideology was meant to destroy. Toward the end of Clarke’s performance piece from the film, “Portrait of Jason,” the unseen narrator asks, “How long have they sang about the freedom, the righteousness, and the beauty of the Black man and ignored you? How long?” Riggs prefaces this performance moment with the Ice Cube quote, “true n—– ain’t f——!” discussed above. As previously mentioned, Cube makes it clear throughout the song that he viewed Blackness and queerness as incommensurate. Instead, the vision of blackness Cube advocated was naturalized as male and heterosexual. Riggs’ film draws on Black lesbian feminist critique. It also anticipates Cohen’s critique of a single-oppression framework, offering a way to understand the danger of a political mobilization that prioritizes racial terror as the singular axis of Black experiences while neglecting other forms of gendered, sexual, and class-based oppression. Black queer folks’ challenges to this paradigm are brought to the forefront as Riggs presents an example of “narrow nationalism” alongside commentary from folks who bore the brunt of its homophobia and exclusion.

In the 1996 film, The Watermelon Woman, Black lesbian filmmaker Cheryl Dunye presents the audience with a film about a fictional documentary that is being created by a Black lesbian filmmaker of her same name. Throughout the documentary, the character Cheryl conducts archival research, personal interviews, and film analyses in hopes of uncovering the (fictional) life of the “Watermelon Woman” also known as Faye Richards. Cheryl is friends with another Black lesbian woman, Tamara, with whom she works in a movie store. During the film, Dunye chooses to showcase a variance in embodied Blackness by allowing some points of contention to manifest between Cheryl and Tamara – one of these resulting from Cheryl’s choice to date a white woman. This particular storyline within the film draws out and critiques essentialized notions of Blackness which suggests that Black folks who choose to date white people are betraying their own Blackness and the broader Black community. In a conversation following a double date, Cheryl and Tamara have an argument in which Tamara interrogates Cheryl’s obsession with “white girls who want to be Black,” and closes with, “what’s up with that Cheryl, you don’t like the color of your skin nowadays?” Cheryl responds to Tamara asking, “Who’s to say that dating someone white means I don’t wanna be Black.” This extended engagement calls into questions the perpetuation of essentialist demarcations of community even within what Patricia Hill-Collins refers to as “subpopulations.” Through this conversation, Dunye asserts that not only is there no one way to be Black, but there is also no one way to be a Black queer, echoing E. Patrick Johnson’s reflections on Black Is, Black Ain’t: “when African Americans attempt to define what it means to be black, they delimit the possibilities of what blackness can be.”

Dunye’s pushback against the exclusion of Black queers with white partners from Black and Black queer community is accompanied by the incorporation of Black lesbian acknowledgement and affirmation of Black women’s beauty throughout the film. Tamara uses descriptors like beautiful, fine, and cute to describe many of the Black women she encounters. In the scene set during a performance at the “Sistah Sound” community center, Cheryl gets upset with Tamara after catching her zooming in on Black women in the audience while she was supposed to be filming the artist on stage. Tamara says, “besides, who can resist capturing all these fine, I mean fine Black women on film.” Dunye emphasizes the presence of Black queer affirmations as a means of resisting the perceived “deviancy” of Black queer sexuality and expressing a radical proclamation of women loving women.

Read alongside the hip-hop of the period as well as other popular cultural productions that reinforced heteropatriarchy, Black Is, Black Ain’t and The Watermelon Woman recenter Black queerness in its myriad forms and interrogate confining visions of Blackness weaponized against queer Black people to marginalize and exclude them. These films interrogate the creation of restrictive criteria one has to meet in order to be considered an authentic member of Black communities.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.