The Difficulty of Uncovering Obscure Lives and Hidden Histories

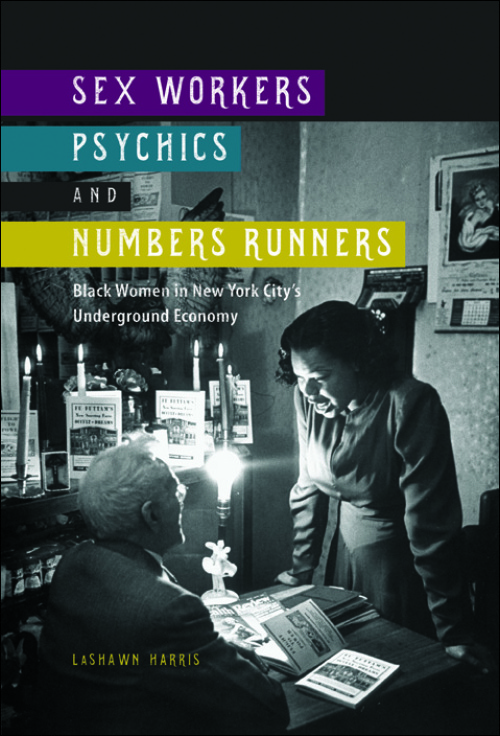

Today is the fifth day of our roundtable on LaShawn Harris’s new book, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy (University of Illinois Press, 2016). On Monday, blogger Keisha N. Blain introduced the book and its author followed by remarks by Julie Gallagher on Tuesday; Shannon King on Wednesday; and Talitha LeFlouria on Thursday. Dr. Harris is an Assistant Professor of History at Michigan State University. Completing her doctoral work at Howard University in 2007, her area of study focuses on twentieth century United States History. Harris has recently published articles in the Journal of African American History, Journal for the Study of Radicalism, and the Journal of Social History. Her first book, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners, examines the public and private lives of an all-too-often unacknowledged group of African American female working-class laborers in New York City during the first half of the twentieth century.

In today’s post, Brian Purnell highlights the strengths of Harris’s evidentiary base but poses critical questions about Harris’s methodologies and analyses of primary sources.

LaShawn Harris’s Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy makes an admirable contribution to a reader’s knowledge of Black women in early twentieth century New York City. I appreciate how Harris highlighted the complicated ways the women who form the core of this book – Stephanie St. Clair, Dorothy Matthews Hammid, and Ella Fitzgerald, with appearances by Billie Holliday and Jackie Mabley – earned money in New York City’s “underground economy.” Despite the hallow cries of early twentieth century moralizing reformists about Black women caught up in gambling rackets, prostitution, and clairvoyance trades, Harris does not tell a one-size-fits-all story of Black women making a living off-the-books.

LaShawn Harris’s Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy makes an admirable contribution to a reader’s knowledge of Black women in early twentieth century New York City. I appreciate how Harris highlighted the complicated ways the women who form the core of this book – Stephanie St. Clair, Dorothy Matthews Hammid, and Ella Fitzgerald, with appearances by Billie Holliday and Jackie Mabley – earned money in New York City’s “underground economy.” Despite the hallow cries of early twentieth century moralizing reformists about Black women caught up in gambling rackets, prostitution, and clairvoyance trades, Harris does not tell a one-size-fits-all story of Black women making a living off-the-books.

Some of the women in this book are tragic. Others are triumphant. Most are just ordinary people dealing with extraordinary conditions of monetary want and suffering.

Racism and sexism compounded their bleak lives. Discrimination based on color, race, gender and class gave these Black women few options for work, high living costs, and far too many social stigmas that judged everything about them as wrong, bad and unworthy.

Still, poor and working class Black women in New York City from 1900-1930 proved capable of doing whatever they had to do in order to live. That is the saving grace of this book: it refuses to turn sinners into saints, or to traffic in one-dimensional depictions. Harris’s subjects are inherently complicated and diverse Black women, and Harris does nothing to smooth over the jagged edges of their lives or round out the contradictions that run through their thoughts and actions. In Harris’s capable scholarly hands, Madge Wundus speaks for so many of the women in this book when she explains why she worked off-the-books, selling hot sweet potatoes from a pushcart in the streets of Harlem, rather than working as a domestic in a white person’s home. Her food hustle on the streets was “easy money,” she said, “dangerous money too, but money nevertheless. It doubled [my] daily income, [and] enabled [me] to do the things [I] had set to do” (41). Some of the women in Harris’s book succeed. Others do not. This book is not without unspeakable tragedy. Throughout Black history, the fates of Nannie Green and Lenora Smith (29-30) occur too often – and once is too often.

Underground economy. Off-the-books. Under-the-table. Unregulated. Veiled. Lumpen. Shady. Hustling. The words and images we conjure to describe the penumbral world of capitalism bespeak the nightmares faced by an historian who seeks to investigate these aspects of the past.

How can a researcher and writer find information and recreate a story about people and practices that, by their very nature, did not want to be found or known?

Or, as Harris writes, “concerns and even fears about the dearth of primary documentation on women profiled in this book made the thought of archival research daunting at times.” What Harris called “the paucity and even unavailability of primary material” must have made researching and writing this book seem difficult, if not impossible.

How did Harris do it? What decisions did Harris make about narrative and analysis, organization and interpretation? How did the lack of sources shape this historian’s work, and what choices did Harris make, and why?

The complicated methods Harris had to adopt stemmed from the difficulties inherent in her chosen historical subject. Those difficulties bear repeating: this is a book about women almost universally condemned by their contemporaries, who perform work that, by its nature, is supposed to be quiet and hidden. If working in an underground economy is spoken about it is done in whispers and hushes, not in the types of public declarations, or even private recordings that create the documents and records that become the tools of the historian’s trade. When such work became public, it often happened because of criminal justice proceedings, or state investigations. Court documents, police reports, welfare office studies, child custody battles – even investigative journalism: when criminal activity is the issue, none of these documents come without serious compromises, biases, and omissions.

Many women in Harris’s book enter the historical record through exactly these types of state records: criminal investigations, arrests, deaths, raids, and sexual assaults. Some black women working in the urban shadow economy became objects of fascination for black novelists and journalist, Blueswomen and poets. In Harris’s use of the Pittsburg Courier profile on Madge Wundus, we hear the street peddler reject public assistance in favor of the independence she experienced working for herself. “It was hard standing on corners swallowing your pride,” Wundus said through a journalist, which becomes a powerful piece of evidence for Harris. “So many were satisfied with relief. Well, no relief for [me]. Better to stand out here in the [streets] and be your own boss” (42).

At times, Harris tries to do too much analytical explanation, with too many theoretical off shoots. In parts, the author tells readers how Black women in New York City’s underground economy reclaimed and reinterpreted urban space, but also suffered from violence inherent in those spaces. Harris analyzes how these women simultaneously prospered and perished in the shady economy, but the reader does not have much of a sense of why one fate, and not another, might befall a particular woman. In Harris’s analysis, the underground economy liberated and ensnared Black women. They entered it to serve their families, and they entered it to augment their own pleasure. But how are readers to make sense of those contradictions? The underground economy involved so many different types of hustles, jobs, and scams –some illicit like prostitution, and some that were legal jobs in underground places, like working the coat check in a speakeasy, or working as the maid in a brothel– that it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish where the shady economy begins and ends.

The complexity is, in part, Harris’s point. These women and their working worlds did not fit into neat categories.

Still, an historian has to take the messiness of the past and, through evidence and narrative and argument, smooth it out into analytical coherence and clarity. Sex Workers, Psychics and Number Runners is an excellent example of how a principled, creative, incredibly hard working social historian can resurrect a seemingly dead, or forgotten subject.

The book teaches readers that there is not one, simple way to understand the obscured lives and hidden histories of Black women working as sex workers, palm readers, and number runners in New York City from 1900-1930. At its best, the book showed Black women’s underground work, and it let the women describe, analyze and explain the meanings of those worlds in their own words.

The footnotes alone make Sex Workers, Psychics, and Number Runners an admirable achievement. If no archive on these women existed before Harris’s researched and wrote this book, one exists now.

Brian Purnell is Associate Professor of Africana Studies and History at Bowdoin College. He is the author of Fighting Jim Crow in the County of Kings: The Congress of Racial Equality in Brooklyn (University Press of Kentucky, 2013), which won the New York State Historical Association’s Dixon Ryan Fox Manuscript Prize. His research, writing, and teaching areas generally fall within the broad field of African American history with specific concentrations in urban history, oral history, civil rights and black power movement history, and modern United States history. He is writing an African American history of New York City since 1626 and an oral history-driven narrative of the Brooklyn-based activist-educator, Jitu Weuis.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.