The Deep Roots of Afro-Asia

(Source: https://bermudaradical.wordpress.com)

This post is the first of a short series on Afro-Asia—the cultural and political exchanges and historical connections between people of African and of Asian descent. In subsequent installments, I sit down with Yuichiro Onishi and Robeson Taj Frazier to discuss their recent books on the subject. Guest blogger Crystal Anderson will also share some of her recent work on the cultural representations of Afro-Asia.

More often than not, when my students hear the terms “Afro-Asian solidarity,” they usually point to the Rush Hour movies, featuring the talented duo Jackie Chan and Chris Tucker. When I taught a group of high school students last summer, their faces lit up when they suspected I might show a clip from one of the movies. They were wrong. I showed a video clip of Fred Ho and his Afro Asian Musical Ensemble instead. I wanted my students to think about Afro-Asia as part of our ongoing conversation about the meanings and functions of black internationalism. Since none of them had heard of Fred Ho (1957-2014), I was also excited to introduce them to this musical genius, writer, and activist.

My students were astute to draw a connection to Rush Hour. Our popular memory continues to associate Afro-Asia with a myriad of cultural productions including novels—i.e. Frank Chin’s Gunga Din Highway and Ishmael Reed’s Japanese by Spring—and films such as Unleashed, Cradle 2 the Grave, and Rising Sun. The Rush Hour movies, first released in 1998, certainly exemplify the cultural manifestations of Afro-Asia even as they perpetuate racial and ethnic stereotypes.[1] Describing Rush Hour 2, in particular, Crystal Anderson argues that the film “embraces interethnic male friendship, but only on the basis of a reductive notion of national identity, which reinforces the distance between the African American and Chinese leads.”[2] This is true but I also think the portrayals of two police detectives—one African American and the other Chinese—working in tandem to fight crime in the United States and abroad symbolically allude to a richer, deeper, and dynamic history.

Indeed, the historical experiences of peoples of Asian and African descent have been deeply intertwined for centuries. “From the earliest days of the United States,” Fred Ho and Bill Mullen explain, “Africans and Asians in the Americas have been linked in a shared tradition of resistance to class and racial exploitation and oppression.”[3] In a 1905 speech, civil rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois acknowledged the link between the “color line” and ‘Yellow Peril.’[4] The racist ‘yellow peril’ ideology of the late nineteenth century, which stemmed from white fears and anxieties over Asian immigration, persisted well into the twentieth century and extended beyond national borders. The negative images and stereotypical depictions of Asian cultures that dominated Western mass media mirrored the pervasive global racist attitudes towards African Americans, and other people of color.[5] Du Bois understood this connection and during the early twentieth century, he advocated political collaboration and solidarity between peoples of African and Asian descent.

Like Du Bois, countless black activists promoted Afro-Asian solidarity as a radical political response to global white supremacy. A number of historical developments strengthened this point of view including Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) and Japan’s withdrawal from the League of Nations in 1933 (a direct refutation of Western control). During the 1930s, many viewed Japan’s military victories as a symbolic triumph against global white supremacy. Many of these same individuals overlooked Japan’s aggressive attempts to colonize China. In 1931, members of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA)—the largest and most influential global black nationalist movement of the twentieth century—grappled with this issue in the Negro World newspaper. “No true Garveyite who is instinctively anti-imperialist will show sympathy to the imperialist activities of Japan in China,” the unidentified writer began. “However,” they continued, “Japan’s high-handed action in Manchuria has opened new opportunities for the triumphal march of Garveyism.”[6] While criticizing Japan’s military aggression towards other people of color, the author proceeded to explain that Japan’s rise would still benefit people of African descent—especially those who advocated political self-determination.

Source: http://www.blackleftunity.org

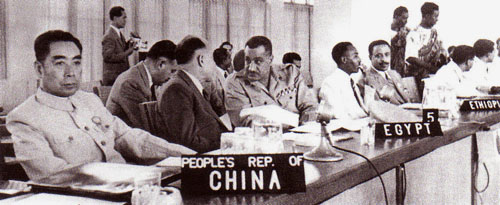

Years later, the 1955 Bandung Conference, held in Indonesia, represented a watershed moment in the history of Afro-Asian relations. Organized by a small group of prime ministers—Muhammad Ali (Pakistan), Jawaharlal Nehru (India), U Nu (Burma), John Kotelawala (Ceylon/Sri Lanka), and Ali Sastroamidjojo (Indonesia)—the conference brought together representatives from twenty-nine developing and non-aligned nations. The core principles of the conference included human rights, sovereignty, Third World solidarity, mutual respect, and political self-determination. It functioned as a critical site for these leaders to promote Afro-Asian solidarity; agitate for the end of colonialism; and ultimately blaze a path towards liberation and independence. As historian Penny Von Eschen and others have argued, the 1955 conference challenged the legitimacy of a bipolar, Soviet-U.S. world during the early Cold War. It ultimately served as the catalyst for the Non-Aligned Movement, laying the ideological groundwork for subsequent conferences including the Non-Aligned Conference, held in Belgrade in 1961.

By the time the first Rush Hour movie was released in September 1998, the Bandung Conference was a distant memory. However, the movie would become a segue into the subject of Afro-Asia—the cultural and political exchanges and historical connections between people of African and of Asian descent. Beyond creative storytelling, martial arts, and Hollywood cinematography, there is a long and rich—yet oft-ignored—history of how people of African descent and those of Asian descent have joined forces to eradicate global racism, colonialism, and white imperialism. As the recent #Tokyo4Ferguson protests reveal, this history is one that continues to unfold.

(Source: http://globalvoicesonline.org/)

[1] Crystal Anderson, Beyond The Chinese Connection: Contemporary Afro-Asian Cultural Production (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2013), 7.

[2] Anderson, Beyond The Chinese Connection, 45.

[3] Fred Ho and Bill V. Mullen, eds., Afro Asia: Revolutionary Political and Cultural Connections between African Americans and Asian Americans (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 3.

[4] See Reginald Kearney, “The Pro-Japanese Utterances of W.E.B. Du Bois,” Contributions in Black Studies, Vol. 13, Article 7 (1995).

[5] Erika Lee, ‘The ‘Yellow Peril’ and Asian Exclusion in the Americas,’’ Pacific Historical Review 76 (2007): 537–562; Eiichiro Azuma, Japanese Immigrant Settler Colonialism in the U.S.-Mexican Borderlands and the U.S. Racial-Imperialist Politics of the Hemispheric “Yellow Peril,” Pacific Historical Review 83, (2014): 255-276.

[6] “Garveyism’s World Opportunities,” Negro World, 5 December 1931.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Fantastic post, Dr. Blain. I am looking very forward to this series, and the unique perspectives that you, Onishi, and Frazier bring to the topic. I’m especially intrigued to hear more on Onishi’s analysis of Du Bois’s thought and more about Frazier’s experiences as an exchange student in China and how those experiences have informed his book. Great work!