The Criminalized Majority

by Dan Berger and David Stein

“Everyone should go to jail, say, once every ten years,” opined novelist and poet Jesse Ball in a recent LA Times article. It may seem like Swiftian satire, but Ball’s proposal is earnest. Addressed “to a nation of jailers,” he argues that a brief but regular stint in jail would serve as the necessary correction to make such institutions more livable–and perhaps less common. “Just think,” he writes, “if everyone in the United States were to become, within a 10-year period, familiar with what it is like to be incarcerated, is there any question that the quality of our prisons would improve?”

But this is an open question. Asking everyone in the country to spend a night in jail could just as easily produce a society of docile subjects, perpetually fearful of challenging the status quo. And this modest proposal confuses the role political elites played in creating mass incarceration. On numerous issues, politicians have resisted popular opinion–especially those from the left. It will take more than changing public opinion to dismantle mass incarceration.

Yet such logic is common. As the problem of prisons, at least in the form of “mass incarceration,” has become publicly condemned, one can find a number of articles making similar claims. Michelle Alexander begins her bestselling book, The New Jim Crow, in similar fashion. “This book is not for everyone,” she writes in the preface; rather it is for people who “do not yet appreciate the magnitude of the crisis…of mass incarceration.” Though she later says the book is also for those “locked up or locked out of mainstream society,” the book remains addressed to an imagined idea of “mainstream society” who presumably lies outside the perils of criminalization.

Such framing suggests that mass incarceration is a result of slumbering moral values. One only needs to awaken these values and mass incarceration will whither away. The trope assumes an identity of its readers: someone with little or no intimacy with the systems of policing and imprisonment. Eliciting an overdue moral outrage, many people writing on prisons speak in the second person: “we must pay attention to prisons.”

Novelist and critic Sylvia Wynter always insisted one ask: who is the “we” that is being enlisted? Written to garner sympathy, framing stories about imprisonment in this way mystifies how imprisonment is experienced by a multitude of people. These stories ask the reader to disidentify with their own experiences being arrested–with or without cause–with their own experience of when they had to spend a night in jail, or two years in prison. It asks them to ignore the imprisonment of their cousin, sibling, parent, aunt, uncle, grandparent, their friend from their high school homeroom, and so on. At stake is not just semantics; rather, it is an urgent matter of analytical clarity of what the carceral state is, who it affects, and how it can be dismantled.

This imagined reader bears little resemblance to the far-reaching experience most people in the U.S. have with the carceral system. Approximately 70 million Americans have criminal records. More than one in five people have been arrested, jailed, or otherwise encountered the criminal justice system. By contrast, only 14 million Americans belongs to a labor union. Progressives have rightly cried foul that Donald Trump and rustbelt politicians champion the needs of the nation’s 77,000 coal miners while ignoring those of the 15 million who work in the retail sector. Yet too many discussions about mass incarceration treat imprisoned people and their loved ones as a pitiable tragedy rather than as a powerful political constituency.

“Politics does not reflect majorities, it constructs them,” wrote the great scholar-activist Stuart Hall. The past four and a half decades of mass incarceration have indeed functioned to construct political majorities–or, more accurately, power blocs–for the right through voter disenfranchisement and other forms of civic and social exclusion. Declaring that “we need to pay attention to (or spend time in) prison” elides currently and formerly incarcerated people and their loved ones. Beyond chiding people to “pay attention” to prison, the challenge is to shape politics with those who have been and remain there.

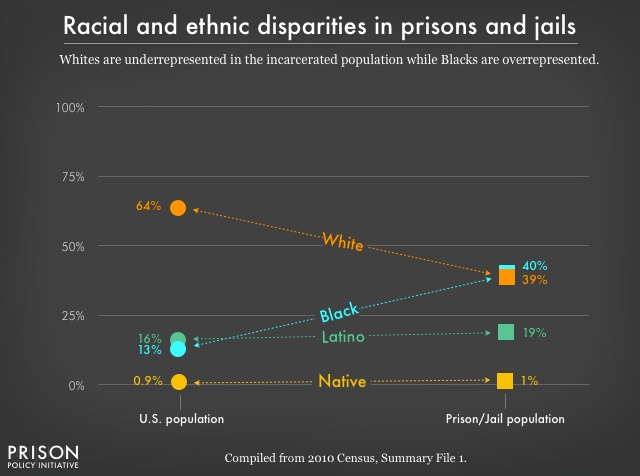

Politics, as theorist Chantal Mouffe has suggested, is about expanding that sense of who counts as “we, the people.” Seen in that light, pleading with people to care for those tragic souls is apolitical: it does not ask readers to consider themselves part of that “we.” Instead of asking “us” to care more about “them” who are criminalized, what if scholars, journalists, activists, and others writing on criminalization proceeded from the assumption that our readers and interlocutors, our friends and neighbors, are already criminalized? Recognizing the vast scope of criminalization does not minimize that those who experience the most severe consequences of criminalization are Black, Brown, indigenous, and/or trans working class people. In fact, recognizing how extensive policing and prisons are helps us understand those processes much better. Similarly, it is not uncommon for some to imagine all white people are absent from the carceral system, even in some cases suggesting that they are immune from its reach. Yet those identified as “white” represent 39% of the people in prison and jail.

Some historical parallels may help illustrate the political importance of understanding the vast reach of the carceral state. Prisons sap the capacity of communities to survive, much less resist. The stress of maintaining bodily integrity and personal security haunts the prisoner, while the challenge of maintaining social and economic stability affects those on the outside–most directly, the mothers, grandmothers, children, and partners of the accused. These strains are part of the daily rhythms of life in many working class communities of color. Recognizing this fact, the Oakland Black Panther Party operated a bus to take people to visit their incarcerated loved ones. Others, no doubt inspired by the GI Coffeehouses that provided respite for soldiers questioning the war in Vietnam, established “support houses” near some prisons. These spaces were gathering points for family members and fellow travelers to gather before or after a prison visit.

In Washington state, for instance, a small group of activists established a “Prisoners Support House” in the town of Steilacoom. An hour from Seattle, Steilacoom housed the ferry terminal through which visitors could access the prison on McNeil Island. Because it was a federal prison, McNeil held people from around the country. As activist Ed Mead wrote about his time at the house in 1972, it “provided family members with transportation to and from airports and bus and train terminals.” As at prisons everywhere, the visitors to McNeil were “usually women and children, along with an occasional brother or father.” They would be given food, meals, and transportation to and from the ferry terminal aligned with visiting hours. The house ran on donations; like similar projects, it folded in the rising tide of repression we now call mass incarceration.

In Washington state, for instance, a small group of activists established a “Prisoners Support House” in the town of Steilacoom. An hour from Seattle, Steilacoom housed the ferry terminal through which visitors could access the prison on McNeil Island. Because it was a federal prison, McNeil held people from around the country. As activist Ed Mead wrote about his time at the house in 1972, it “provided family members with transportation to and from airports and bus and train terminals.” As at prisons everywhere, the visitors to McNeil were “usually women and children, along with an occasional brother or father.” They would be given food, meals, and transportation to and from the ferry terminal aligned with visiting hours. The house ran on donations; like similar projects, it folded in the rising tide of repression we now call mass incarceration.

One of the most powerful developments over the past decade of anti-prison activism has been enhanced language to understand politically and publicly what many had previously experienced privately. Most clearly displayed in the work of organizing by formerly imprisoned people, such efforts re-made a political constituency. Many criminalized people, as this organizing makes clear, understand their experiences through the prism of the U.S.’s long history of oppression. They identify with and draw inspiration from freedom fighters of past eras. And they articulate clear pathways to reduce size and scope of the carceral system.

Personal experience–the narrow “we”– is not the only way of generating political constituencies. One need not have been to prison themselves or be the child of an imprisoned person to fight alongside those who have. After all, the tentacles of state violence can grab “us” at any moment. That is and always has been a central tenet of Black radical opposition to law and order politics. By contrast, the recent report from the Center for Popular Democracy, Black Youth Project 100, and Law for Black Lives argues that all those who want “more money for infrastructure, job training and placement, affordable housing, drug rehabilitation, educational support, youth programs and jobs, healthcare, and mental health services” have a stake in opposing policing and punishment. Such a frame recognizes that ideology, moral values, and a vision of a better world directs politics. That convergence, not personal experience, drives how political coalitions, the broad “we,” get established and mobilized, and win.

Instead of writing for or imagining a “we” that is somehow immune or separate from criminalization, let us instead follow the lead of Black feminist culture workers. “We are the ones we have been waiting for,” June Jordan wrote in a poem celebrating the mass movement against apartheid. “We who believe in freedom cannot rest,” sang Sweet Honey in the Rock, quoting legendary organizer Ella Baker. In these and other refrains, “we” are the oppressed majority. We are those who stand up against injustice. And that is a we powerful enough to defeat the carceral state.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.