The Consequences of USCT Soldiering

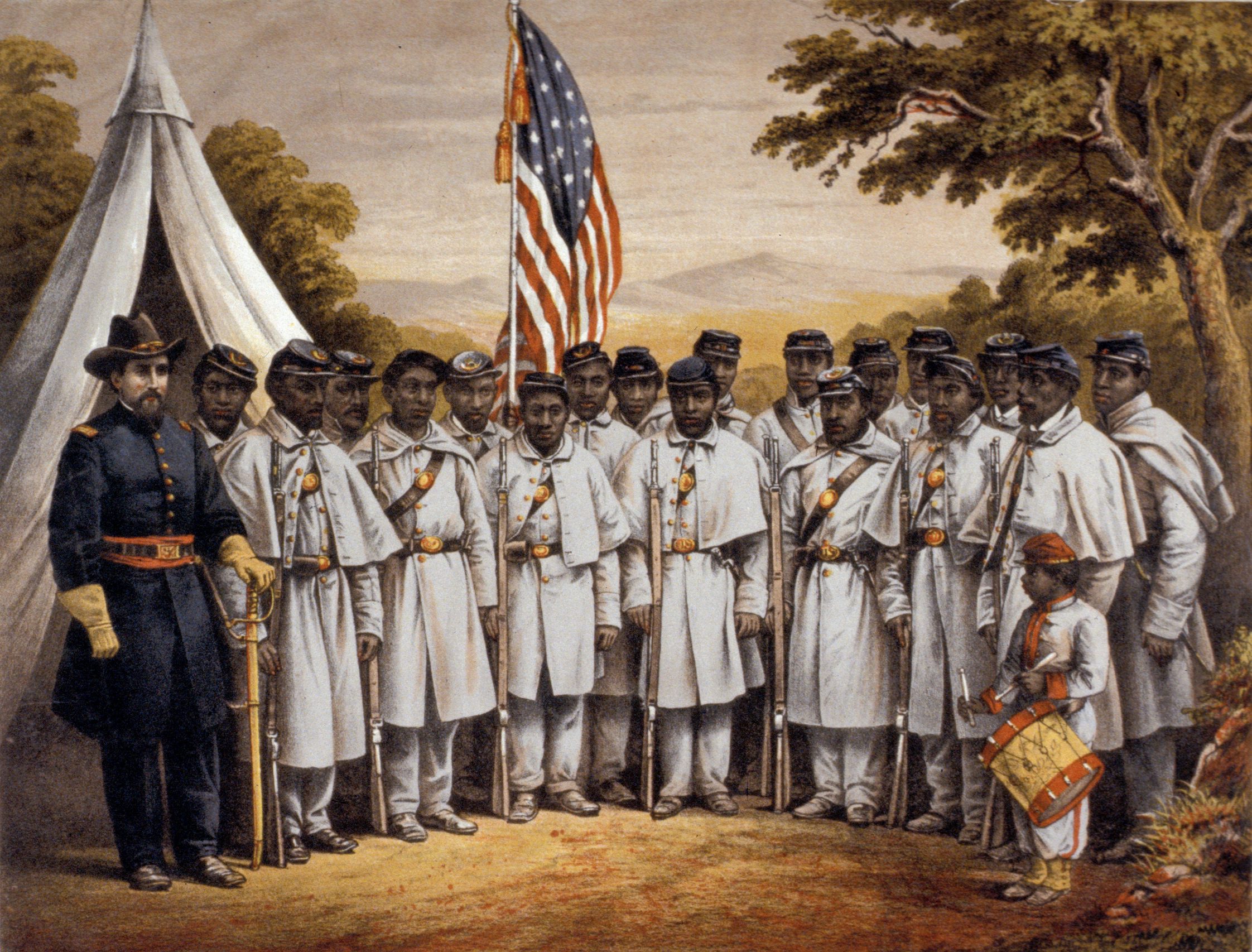

Solomon Wilson, a Thirty-First United States Colored Infantry (USCI) soldier, died in a regimental hospital on August 6, 1864. An unknown illness took his life while he served in Petersburg, Virginia. Wilson’s passing went unnoticed by many people who lived through the Civil War. On both the home front and front lines, death and violence were ever-present and, in many cases, inescapable. For instance, nearly 1.5 million casualties occurred during the war, which denotes those families and communities experienced significant losses.

Unfortunately for the Brown family (who lived in Baltimore County, Maryland), the U.S.’s mobilization of Black regiments tragically impacted their entire household decades after Robert E. Lee’s surrender. The lives of four household members—father and siblings—forever changed when Lee Othello Brown, a twenty-two-year-old, chose to leave his home in May of 1864 and enlisted in a United States Colored Troops (USCT) regiment. Brown never disclosed the motivating factor(s) that influenced his departure. Little did he or his family know that this was the last time the entire family would see each other alive.

By 1864, USCT enlistment rhetoric was inescapable in various free Black communities. Much like the people encouraging Black men to enlist, the rhetoric differed greatly. Frederick Douglass emphasized that military service was a duty of citizenship that Black men previously performed and must perform again. William D. Kelley asserted that soldiering was a quintessential aspect of manhood. Meanwhile, Anna Dickinson argued that militarized violence was pivotal to the U.S. citizenship demands of Black men by saying, “The black man will be a citizen, only by stamping his right to it in his blood. Now or never!” Perhaps their collective efforts of pro-enlistment advocacy influenced Brown’s decision to join.

It is also plausible that financial inducements mattered to Brown in the form of bounties. Maybe his bachelorhood (combined with his occupation as a laborer) led to Brown wanting to collect a bounty—federal and local—to potentially amass a significant one-time payment that was, in many cases, immediate cash injections to enlistees. Bounties grew in normalcy after the U.S. Congress passed the Enrollment Act in 1863, which mandated each state with a required number of enlistees or a local draft would occur. Numerous northern states responded to the federal policy by offering sizeable bounties, particularly for Black men (in and outside each state), because each Black recruit “spared” a white man from serving. Even individuals who held staunch anti-Black views would later celebrate Black soldiering, especially once the U.S. war aim, after the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, changed to ending slavery rather than reunification. For instance, a white Illinois man professed, “ ‘Let the negro-hater remember that every black [man] who enlists in Illinois, counts ONE and take[s] the place of a white man, perhaps himself.’ ”

Regardless of the motivation(s) of those raising bounty funds, it was possible for men to (sometimes) earn hundreds of dollars, which illustrates that there was a business aspect to enlistment. Maybe Brown found the money appealing, though he would not receive his federal bounty (of one hundred dollars) until he mustered out of military service. Officials possibly feared that he would take his bounty money and refuse to serve, which was common for bounty jumpers.

Due to these, or other reasons, Lee Othello Brown made his way to New York, New York, and enlisted in the Thirty-First USCI on May 25, 1864. For unknown reasons, he stated that he was born in New York and that his name was Solomon Wilson when he joined. He never disclosed the reason(s) for the name change. Tragically, Wilson only “lived” for about three months until his unfortunate passing.

Not long after, John Brown (Lee’s father), with the help of friends, sought assistance navigating the Civil War pension system. Even though a Pension Bureau investigator noted in 1864 that he believed John’s claim that he was the father of Lee Othello Brown/Solomon Wilson, the case remained open until 1892. After a twenty-seven-year-long battle, the Pension Bureau awarded John, his son’s one hundred dollars federal enlistment bounty. It is most likely that the passage of the 1890 Dependent and Disability pension law exponentially expanded veterans’ eligibility and some of their kin who applied for Civil War pensions.

John’s decades-long battle highlights numerous issues he experienced while struggling with the Civil War pension system. Firstly, it was a highly bureaucratic (and in many confusing and financially costly) application process involving lengthy investigations for numerous reasons. Unfortunately, each pension agent’s views—on race and gender—were also factors that influenced their rulings, which were often rejections. However, even in John’s case, a supportive pension agent did not assure an approval would (immediately) occur.

However, John’s determination illustrates his commitment to remembering his son’s sacrifices (which contributed to ending slavery and defeating Confederates). There is no question that John financially benefitted from the additional money. At the same time, his persistence highlights that he wanted the federal government to both documents and acknowledge the lasting impact of his son’s military service on his kin. Given that this all took place during the Jim Crow era and the rise of the Lost Cause myth (or lie), it is feasible that the Browns celebrated that, through their pension case, the federal government (either intentionally or unintentionally) disavowed a racist historical interpretation that numerous white Americans championed. The Pension Bureau acknowledged that John Brown’s demands for the Families’ Cause were legitimate.

The familial dynamics of the Browns were undoubtedly complex and complicated. Moreover, the war’s impact on their family was unquestionably unique. While they are not representative of nineteenth-century Black people or the families of military service members, they do provide a way to discuss how the war impacted families. Because decades after Lee’s surrender, Black families continued fighting for the U.S. to remember their wartime sacrifices.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.