The Connections Between Urban Development and Colonialism

*Editor’s Note: This week we are publishing some of our favorite BP articles. We continue with this essay by historian Paige Glotzer as part of our forum on Race, Property, and Economic History.

“It’s kind of manifest destiny…now the marketplace and the city has begun to catch up.” This is how architect David Manfredi recently described a billion-dollar residential, commercial, and retail complex to be built in 2015 in Baltimore. Speaking to a reporter, Manfredi was emphasizing how the new project he was working on would further extend the upscale development of Baltimore’s old waterfront into formerly industrial territory. His word choice was telling.

“Manifest destiny” was a phrase coined in 1845 to call for the westward expansion of white settlement and slavery across North America as well as to sanction Native American genocide and a war with Mexico. Probably unwittingly, the architect spelled out the real yet subtle connection between contemporary urban development across North America and the history of settler colonialism. These ostensibly distinct “destinies,” in Baltimore and the West had common roots in colonial and imperial investment dating back over a century.

Long before upscale glass high rise complexes dotted Baltimore’s harbor, earlier developers planned some of the first segregated suburbs in the United States, and they did so with the aid of British investors. Financed with capital from four hundred British shareholders in 1891, the newly created Roland Park Company worked to ensure long-term returns for its investors by experimenting with racial segregation. The Roland Park Company sought to deliver steeper returns with racial exclusion. The Company spearheaded the use of racially restrictive covenants as a way to boost the value of their residential communities. Such contracts, first used in Baltimore’s affluent suburbs, contained strict community-wide rules that made no distinction between prohibiting Blacks, livestock, and factories. Each appeared in a long list of banned “nuisances.”

The deeper connections between an earlier era of urban development and colonialism become apparent when looking at these shareholders and where they got the capital that they invested in the forms of segregation that became foundational for the rise of Jim Crow. Two of the Roland Park Company’s biggest investors have a traceable history of previous business ventures that gave them the capital to invest in Baltimore. Both Alfred Fryer and Jacob Bright had become wealthy through colonial investments in the mid-nineteenth century.

Alfred Fryer (1830-1892) began to accumulate capital as a Manchester sugar refiner in the 1850s, processing cane from the Caribbean. At that point, sugar production in the Caribbean was still deeply connected to the structures of the slave economy. Great Britain had abolished slavery in the Caribbean in 1833, providing compensation for slave owners, but the enslaved themselves received nothing. On the island of Antigua, many free Blacks left the sugar estates for part of the week to work in markets or at the ports; however, contract laws and bad economic conditions ended part-time estate work. Little land existed outside the estates, allowing planters to reestablish the labor and legal regime that had existed under slavery over the next three decades. Even Blacks who left the estates to found new villages often remained tied to the sugar economy. For example, many of the formally enslaved produced the specialized hats that Black workers wore when ploughing fields. Yet others moved from one estate to another looking for the least brutal conditions under which to work.

Fryer’s entry into Antigua was facilitated by the West Indian Encumbered Estates Act (1854). This act further enriched former slave owners by abrogating debts on the land. Antigua planters welcomed the act and intermediaries did swift business in buying and reselling estates. Fryer took the opportunity to purchase six estates, eventually founding the Fryer’s Concrete Company along with other British engineers and sugar refiners. The company produced a durable crystallized sugar product called “concrete,” which it then shipped to refiners in England. But if concrete was processed in Fryer’s own patented sugar machinery, the labor involved in actually growing and harvesting the sugar was the cheapest available. Before emancipation, the land that came to be Fryer’s estate was worked by at least 1,137 slaves, many of whom (as well as their descendants) ended up working for Fryer’s Concrete. Fryer’s business, in short, depended on continuing the exploitation of black labor under colonial conditions.

Jacob Bright (1821-1899), in turn, was an owner of cotton mills outside Manchester who became one of the Fryer’s Concrete investors. But Bright had his hands on many other ventures as well. He carried on his family’s political legacy as a Liberal member of parliament from 1867 until 1895. Over those decades, he invested in land, government bonds, banks, and companies on four continents. In January 1885, Bright assumed the directorship of the British Congo Company, having helped to defeat a British treaty that would have given Portugal control over the Congo River Basin. He anticipated that the company would soon gain access to the land and resources around the basin—and he was right. The 1884–85 Berlin Conference, involving the United States and European powers, formalized many of the mechanisms of European colonialism over the African continent. The conference gave rise to the Congo Free State, which granted trading rights to the British in the river basin. The British Congo Company’s boats gained access to the river and supplied material the company then exported.

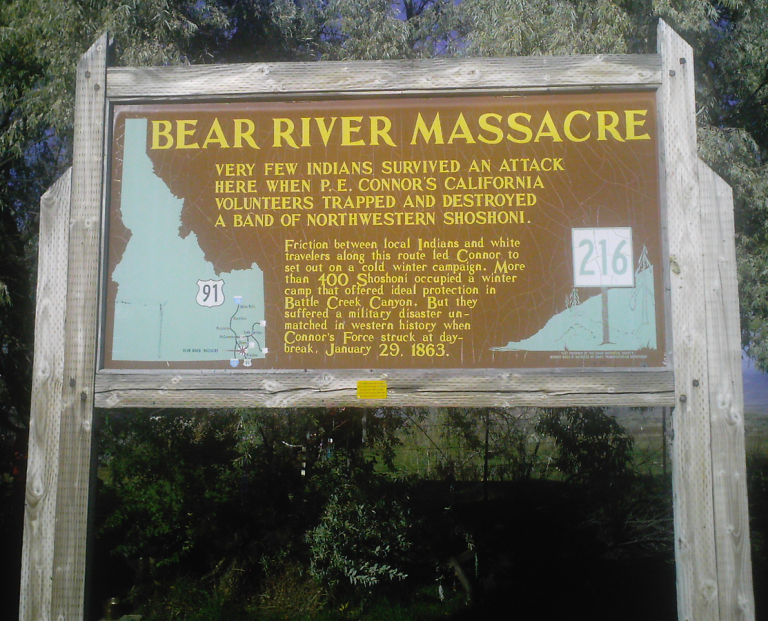

Kansas City financiers Samuel Miller Jarvis (1853-1913) and Roland Ray Conklin (1858-1938) concentrated their capital into US westward expansion, thousands of miles away from Antigua and the Congo. White settlements in what is now Utah and Idaho were making survival increasingly difficult for local Northwestern Shoshone Indians. In 1863 federal troops retaliated for a Northwestern Shoshone raid by killing three hundred men, women, and children in the Bear River Massacre. This spurred negotiations between the Northwestern Shoshone and the federal government, opening the area to state-sponsored settlements and enabling railroads to run their rights of way through the valley. The railroads sold land near the tracks to two Jarvis and Conklin, who formed the Bear River Canal Company to supply water to towns in Utah and Idaho. Jarvis and Conklin may not have displaced members of the Northwestern Shoshone themselves, just like Fryer did not employ slaves. However, they made advantageous business decisions directly based on the results of colonial state violence. The primary customers of Bear River water were the very ranchers who settled the area and who employed Northwestern Shoshone as low-paid seasonal farm laborers and domestic servants. Jarvis and Conklin also sold canal bonds to British and Scottish investors. Fryer was one of them.

In 1887, Jarvis and Conklin reached out to Fryer about a new venture, who, in turn, brought Bright on board. They founded the Lands Trust Company in London the following year. The company released a mission statement declaring that it would purchase “lands in those more newly settled parts of the United States, or in the Colonies, where from the influx of population they are rapidly enhancing in value.” 1 Such a mission struck a chord among members of the British public, who subscribed to all 500,000 shares of the company, at one pound each, within three months. The lands they invested in included not only western territories that stood in the path of white settlement, but also property on the peripheries of rapidly growing cities such as Chicago, Cleveland, and Baltimore, where affluent whites sought places to live away from central cities. For some, this might have been the only investment they made in their lifetimes. For others, such as Fryer and Bright, the Lands Trust Company was simply the latest of their globe-spanning investments, funded by the ones that preceded it.

In 1891, the Lands Trust Company financed Baltimore’s Roland Park Company, which went on to develop a 2500-acre district in northern Baltimore that remains one of the majority-black city’s whitest and wealthiest enclaves. Here, as in the Antigua, the Congo, and Utah, profit was predicated on white settlement. Beyond the masonry walls, tall hedges, and dead-end streets that constitute the district’s well-defined borders, lay impoverished neighborhoods inhabited by those that deed restrictions excluded for the sake of returns on the investment. The practices pioneered by the Roland Park Company effectively tied real-estate profit to racial exclusion in ways that would inform federal housing policy in the decades to come. These policies have made it extremely difficult for blacks to build and pass on wealth. Linking all of these apparently unconnected ventures is not just a common source of investment in British shareholders like Fryer and Bright, but in how they reaped profits from the dispossession of land and wealth from people of color.

Given the history of development in Baltimore, it is fitting that one of the architects responsible for Baltimore’s harbor project described it as a “kind of manifest destiny.” Those links continue into the present. Manfredi works for Corporate Office Properties Trust (COPT). Though relatively understudied, Real Estate Investment Trusts channel international capital into urban property development. COPT specializes not only in urban real estate but tools of present-day American imperialism: national security and defense property for the U.S. government. By referencing manifest destiny, the architect tapped into the deep connections linking American real estate and colonialism.

- Prospectus for the Lands Trust Company, London Metropolitan Archives, London Stock Exchange, Applications for Listing CLC/B/004/F/01/MS18000/23B/S49. ↩

This article was very enlightening and has motivated me to continue researching this long history of business and residential segregation, all in the name of future profits. My heart aches sometimes because it’s this history that fails to make the pages of secondary and post-secondary history books. Maybe it’s being taught in the law and business schools. So many of us still believe that racism is about a personal dislike for another person when it’s simply about power. In the case of this article, economic power and political power. So much of our retirement and educational funding comes from investments made by companies that were built on the premise of racial segregation. Further, as we invest, we’re supporting companies with this long history. How do we drill down through the layers and discern which companies to invest in? How do our local politicians approve permits with the discernment that prevents supporting a company whose foundation and motives are based on segregation. I don’t know whether to cry or scream!!!