The Complexities and Contradictions of the Nation of Islam

This post is part of our online roundtable on Ula Taylor’s The Promise of Patriarchy

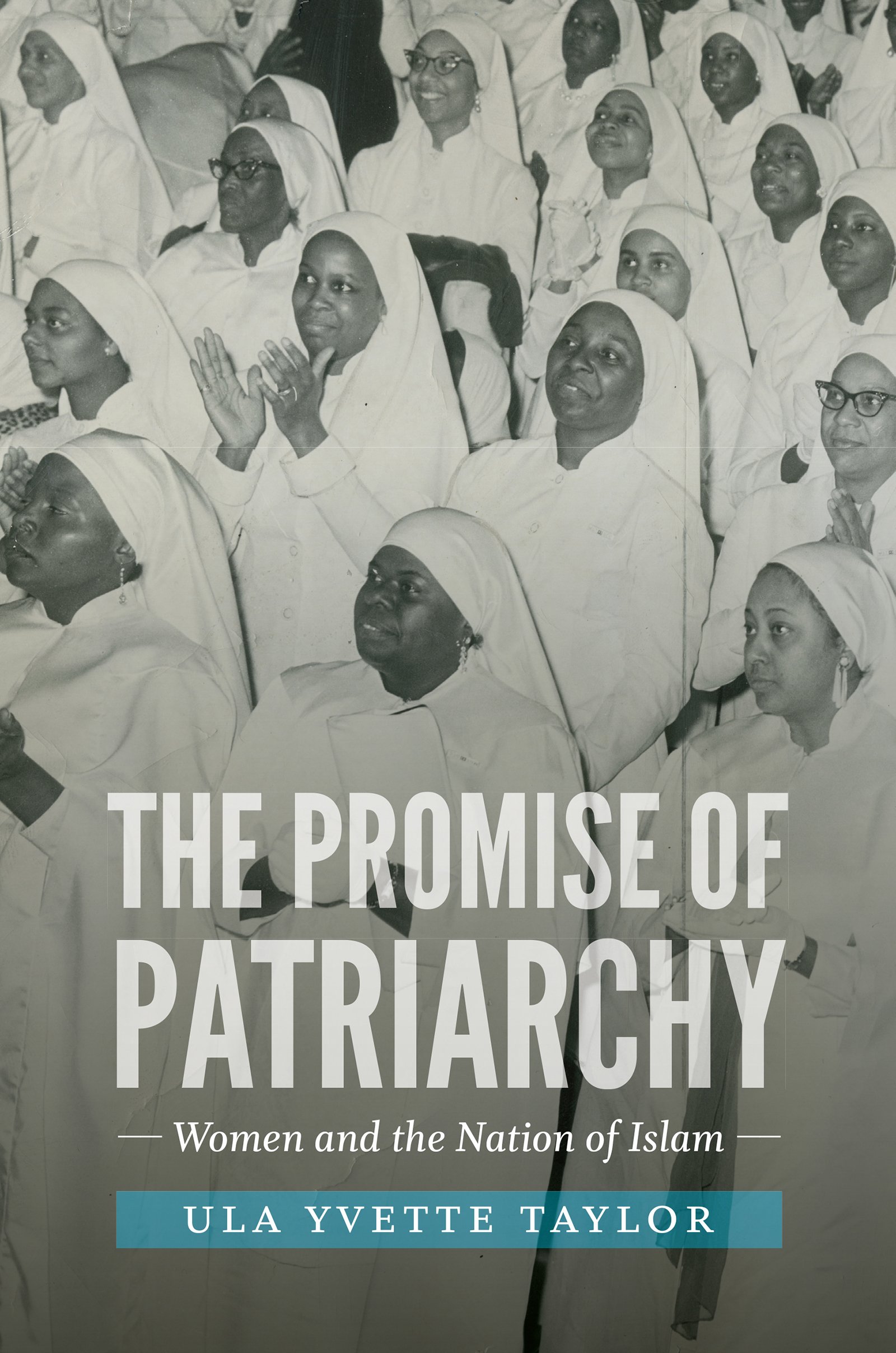

In The Promise of Patriarchy: Women and the Nation of Islam, Ula Y. Taylor examines the complexities of race, gender, class, and sexual politics in the movement from 1930 to 1975. Taylor investigates Black women’s attraction to and lives within the Nation of Islam (NOI) as they navigated shifting economic and political realities in the context of the Great Depression, World War II, the Cold War, and the Civil Rights, Black Power, and women’s liberation movements. Taylor masterfully constructs an archive, piecing together diverse and oftentimes limited sources to illustrate a complex picture of women’s experiences and choices within the movement. By centering women, Taylor intervenes in dominant narratives of the NOI. The Promise of Patriarchy is an instructive text that not only re-narrates the history of the NOI, but also reveals the deep complexities and contradictions of the movement by using an intersectional lens.

Taylor’s archival excavation reveals that women’s labor was foundational to the development of the NOI from the very beginning of the movement. Clara Poole, wife of Elijah Muhammad and the matriarch of the NOI Royal family, first introduced her husband to W. D. Fard, architect of the movement. Poole’s efforts to remake her husband, who struggled to keep a job, into a provider for her family set the path for Elijah to find purpose and to rise to power. Because Elijah could not read, he depended on Poole to read things to him. Without Clara Poole, the Nation of Islam and Elijah Muhammad as we know them would not exist. In the early years of the movement during the 1930s women went door to door spreading Fard’s message. Women ran the Moslem Girls’ Training and General Civilization Class (MGT-GCC) that trained women in domestic duties, they helped to establish the University of Islam schools for children, they wrote articles in The Final Call to Islam, and they were indispensable in both the daily functioning of the NOI and recruitment of new members to the movement. Women, however, could not serve as ministers and gender hierarchy shaped every aspect of their lives. The NOI demanded that women take a secondary role both within the family and within the movement. Like the women of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, the Civil Rights Movement, and Black Christian churches, NOI women did the heavy lifting that kept the organization afloat although histories of these movements tend to highlight male figureheads.

As The Promise of Patriarchy reveals, no singular narrative captures the dynamics of NOI women. The NOI attracted Black women from a variety of backgrounds and social locations. Because of this diversity “NOI women experienced patriarchy unevenly and in unpredictable ways” (178). Taylor’s work uncovers the lives and choices of both known and unknown NOI women. Singer Etta James joined the Atlanta Temple in 1960 and poet and scholar Sonia Sanchez joined the movement in 1972. A former SNCC activist, Gwendolyn Simmons, known as Sister Gwendolyn 2X, held a leadership role in the National Council for Negro Women while simultaneously living as a member of the Nation. Social and financial capital afforded high profile women like James, Sanchez, Simmons, and Belinda Ali, wife of Muhammad Ali, a different set of options and means to navigate NOI patriarchy. Sonia Sanchez was able to skirt the NOI rule that banned women from working at night by paying a male escort to accompany her. Etta James continued to eat pork and wear fitted dresses that showed off her cleavage despite her NOI membership. Within the NOI, therefore, “a woman’s financial position impacted how she might be able to navigate patriarchal structures” (177). For Taylor, capturing the complexities of race, gender, class, and status requires an intersectional analysis.

To center women in an analysis of the NOI uncovers the complex contexts in which women navigated the movement. On the one hand, the NOI was often “out of step with mainstream black America” (2). NOI leaders instructed followers to stay away from politics and heavily criticized the Civil Rights movement and integrationists. Yet the growth of the NOI from fifteen temples in 1955 to fifty temples in twenty-two states by 1959 speaks to Cold War realities of McCarthyism, anti-communism, and the persecution of radical thinkers and activists (74). Despite the Nation’s official apolitical stance, women like Sanchez and Simmons saw their membership in the NOI as a continuation of their radical political activism. Directly confronting white supremacy while maintaining puritanical gender and sexual politics, “the boundaries between conservative politics and black nationalist rhetoric were heavily blurred” in the Nation (139). Delving into women’s participation in a movement that at once promised them protection and rendered them secondary to men, Taylor grapples with the very idea of Black radicalism and the extent to which the NOI offered radical possibilities for women. The NOI’s commitment to Black capitalism, uneven sexual politics, and rejection of Pan-Africanism delineate the deep contradictions at the foundation of the movement.

In some ways, the NOI connects directly to the Black nationalist ideology of Garveyism, and Minister Fard “instructed all followers to read works by Marcus Garvey” (19). Unlike Garvey, Fard and Muhammad were decidedly not Pan-Africanists. According to NOI beliefs “the black men in North America are not Negroes, but members of the lost tribe of Shabazz, stolen from the traders from the Holy City of Mecca 379 years ago” (12). The belief that African Americans derive from the “original” people from Egypt, Arabia, and East Asia was an outright rejection of a sub-Saharan African homeland. This origin story and its cultural politics left intact the idea of African savagery and backwardness. According to Malcolm X, after his departure from the NOI Elijah Muhammad was “as anti-African as he was anti-white” (147). Furthermore, for Fard “only black Americans, or the ‘so-called Negro,’ as opposed to continental Africans, could actually embrace this God-given identity” (14). One NOI member refused to send his children to a “colored only” school because they “belong to a different black race” (38). Recasting blackness as “Asiatic” rather than rooted in Africa, NOI members remade themselves as a distinct body separate from both white America and Black cultures they considered lascivious and uncivilized.

Like other Black nationalist movements, the NOI’s remaking of race required heavy surveillance of and control over women’s bodies. Nation rules drew a strict “aesthetic boundary” that sought to physically distinguish NOI women from other Black women (68). The NOI governed women’s clothing, hairstyles, diet, and body weight. Women were directed to eat once daily and were weighed twice a month (162-163). Wearing one’s natural hair texture in an Afro was considered uncivilized and broke NOI rules. Using and even carrying a tampon could cause a woman to be reported (165). Directly confronting dominant representations of Black women such as the overweight Mammy, the oversexed Jezebel, and the dependent welfare queen, the Nation attempted to remake Black womanhood by producing slender, sleek-haired, conservatively-dressed mothers of a new Black nation. “The Nation’s ultrapuritanical code of sexuality” conflicted with the sexual escapades of Elijah Muhammad, who impregnated seven women, including several of his teenaged secretaries, and fathered thirteen children outside of his marriage to Clara. While four of his secretaries were tried in the Chicago temple for being “unwed and pregnant,” Muhammad continued to satisfy his sexual appetite without penalty (129).

Navigating the incongruity between NOI teachings and economic realities, women often made decisions for themselves and their families that were in direct conflict with Nation mandates. In this space between ideology and reality, Taylor highlights women’s agency and what she calls “trumping patriarchy.” In trumping patriarchy, NOI women “found ingenious ways to work within the patriarchal system” (106). Women trumped patriarchy by taking control of family planning and using birth control, which the NOI prohibited, divorcing men who did not fulfil their duties as husbands, and finding opportunities to seize short-term power in the household. By trumping patriarchy, however, NOI women did not intend to dismantle it. NOI women “[broke] the rules of patriarchy in order, ultimately, to support it” in hopes that Black men would live up to the promises guaranteed by the movement (120). Through the conceptual framework of trumping patriarchy, Taylor issues a powerful warning to scholars who investigate Black women’s lives:

It is much easier for scholars to dig in pessimism—to showcase the unloved woman or the disrespected wife as the way to analyze gender domination. But the lived experiences of African American women in general, and of NOI women in particular, demand us to do more” (175).

Our jobs as historians of Black women’s history is “to understand the choices they made in the context of the options available to them” (177). As the women who speak through the archives illustrate, NOI women were making what they saw as the best choices for themselves and their families from the bottom of race, gender, and, for the majority, class hierarchies. The framework of trumping patriarchy situates NOI women as architects of their own lives who make strategic choices, albeit in constrained contexts.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.