The Communist Reimagining of Black History

The American Communist Party was aware that history was a powerful tool. It frequently used history in its propaganda to attract new members, particularly women and minorities. Party schools across the country regularly held classes in labor, Black, and women’s histories. Its newspapers and magazines featured stories on prominent historical figures. Though the Party’s women’s paper, The Woman Worker–renamed The Woman Today-–regularly featured stories about prominent women, it almost never discussed Black women historical figures. After 1949, when Claudia Jones admonished the Party to end its “neglect” of Black women and recognize their triple oppression, the Party began to spend more time fostering Black women’s leadership. Black women’s history became a hallmark of communist publications. Because the Party desperately sought class unity, these articles did not often refer to divisions between working-class white people and minorities. Rebellion against authority, white benevolence, and cross-racial unity were the most common themes in these articles. The Party’s goal with these histories was to solidify class solidarity.

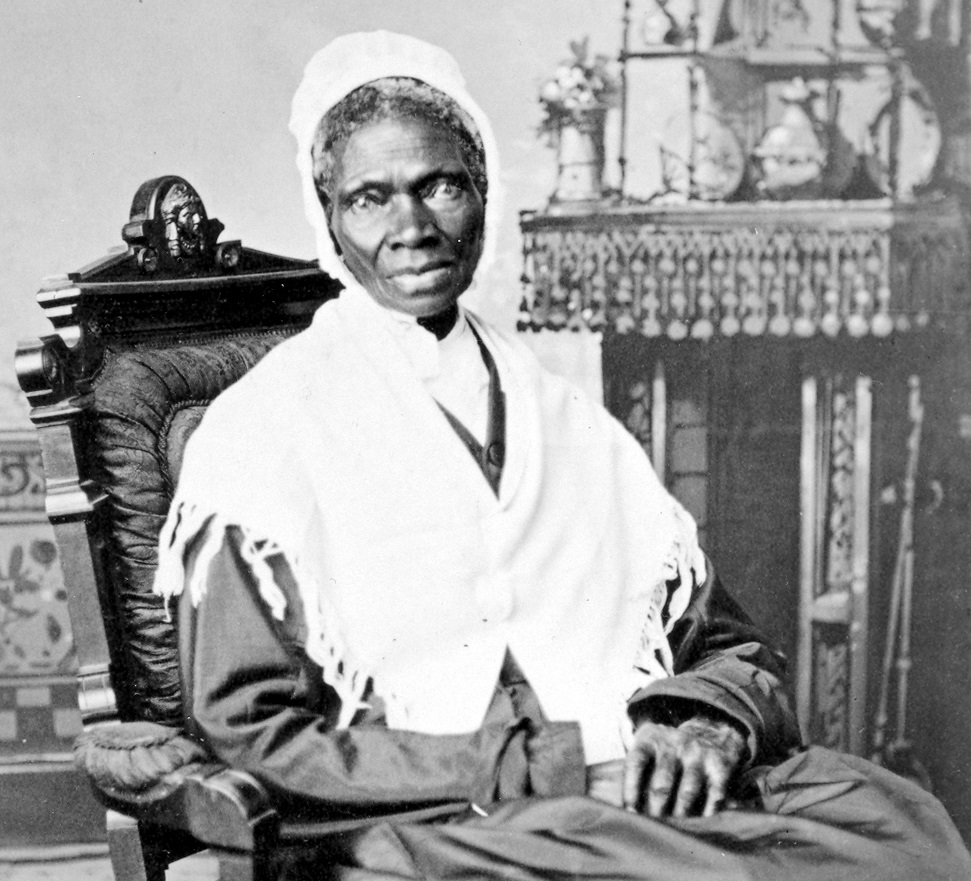

In a December 1936 issue of The Woman Today, there was a small penciled image of Sojourner Truth next to an article on Black women in politics. A brief description portrayed Truth as an “antislavery worker and lecturer” who was renowned for “humor, sarcasm” and quick repartee that often got her out of “difficult situations” accompanied this image.1 Until The Woman Today discontinued publishing in 1937, this was the only reference to a Black historical figure. Though there were occasional references to Black women’s history in other communist publications, Kate Weigand has argued that it only was after Claudia Jones’s article admonishing the Party for its neglect of Black women did the Party give Black women’s history serious treatment.

Articles on Black Women’s history began to appear in the Daily Worker, New Masses, and Masses and Mainstream, and these articles introduced Party members to Black historical figures. Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman were two figures who were frequently featured. The articles about them never mentioned race, nor did they discuss white supremacy or slavery as an institution. Instead women’s resistance to authority and Truth’s and Tubman’s work with like-minded whites was the focus of these articles. The Party sought primarily to inspire and inform, not to analyze whiteness or confront white supremacy. Poor whites invested in white supremacy were absent, and this was in service to the Party’s emphasis on cross-racial unity.

In a May 1950 issue of The Worker, an article appeared on Harriet Tubman authored by Louis Green. Green recounted Tubman’s escape to freedom and her work with the underground railroad. He linked her to the long tradition of rebellious slaves including Gabriel Prosser, Denmark Vesey, and Nat Turner, and he claimed that it was the same spirit of rebellion that influenced Tubman. Tubman’s brothers thwarted her first attempt to escape, according to Green. But thanks to a local white woman, Tubman was given two addresses, directions to get to the first. When she arrived at the first home, a white couple helped to shelter her until they took her to the next station. This benevolence Green claimed was one of many lessons Tubman learned: some white people were “honest and sincere friends” of slaves.2

Though Green briefly mentioned the danger of both Black and white people selling out a runaway slave, the Party tried to convince its members that solidarity was the key to emancipation. Thus white investment in slavery was not referred to in Green’s article. Green lauded Tubman’s bravery in emancipating hundreds of slaves in her many death-defying raids into the South, but it was her work with whites that became his focus. Green highlighted Tubman’s work promoting John Brown and his attack and her desire to join him, though unplanned postponements foiled her work. He noted that Tubman began a “life-long” friendship with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and other abolitionists and suffragists, without any mention of their notorious racism, including Stanton’s.

Green also wrote about Tubman’s Combahee River expedition with her abolitionist friend James Montgomery and the successful liberation of over 700 slaves. He included an anecdote about a railroad conductor, whose race he did not mention, who tried forcibly to remove Tubman from a train and how much that offended Tubman because she fought to end his degradation as much as her own. Green closed with a note on the memorial to Tubman in Auburn, New York, and her legacy as an honored Black woman in American history. The Harriet Tubman story has all the trappings of the white savior complex with benevolent white people who helped bring Tubman to freedom and assisted her in resisting the slave power. It is a narrative that ameliorates white guilt and ignores the whiteness of the slave power.

In 1952 The Worker ran a Black history week story about Michigan abolitionists. A short biopic that featured Truth offered more insight into her life than the 1936 article, but with one glaring absence. Like the Tubman article, there was no face, name, or race associated with the evils of slavery; it was an evil that remained disembodied from white actors. The author Charlotte Williams emphasized Truth’s dogged resistance to slavery and her forceful personality and presence that made Truth the “miracle woman” of her day. Williams wrote about Truth’s speaking engagements in which she “convinced” people that all men should be free. Williams mentioned an “Ohio man” who confronted Truth after a speech and claimed that he did not think her speech would do any good and he would rather a flea bite him. She responded that the “Lord willing” she would keep him scratching. Aside from that confrontation, Williams mentioned no other resistance to the abolitionist’s message.3

Although debates about racial equality frequently divided both abolitionists and suffragists, Truth operated seemingly without resistance from her fellow anti-slavery and suffrage comrades. When legal slavery ceased to exist, and Truth realized “her work was done,” she retired. Other articles on Black and white solidarity in the underground railroad, unified resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act, and the friendship between Frederick Douglass and John Brown accompanied Williams’s article. These sanitized histories did little to enlighten readers about Black history. There was no effort to analyze white supremacy, white investment in whiteness, and the violent and concerted efforts made by rich and poor whites alike to uphold slavery and white supremacy.

What both narratives have in common is a problematic reflection on Black history. Williams and Green had the same goal: to convince their readers that racial solidarity was essential for class unity. Accomplishing this falseness meant telling a tale of two women who were heroes but ignoring that their resistance to white power was what made them courageous. The nameless and faceless slave institution in these stories does not reflect opposition to white power and indeed does not demonstrate the investment of whites in slavery despite class status. Class unity was meant to usurp any racial divisions, and the celebratory history that appeared in the Party’s papers made that argument. The Party preached class unity and the sublimation of other identities, even after Jones’s remarkable article. Throughout the post-emancipation era, an inability to reckon with America’s racial past and recognize the appeal of whiteness over class solidarity for the white working-class has plagued the American Left. Perhaps the real lessons from these histories are that until liberals and the Left genuinely confront their “neglect” of Black women and race, real substantive progress remains out of reach.