The Activist Work of K-12 Educators: Then and Now

Black students’ educational needs are central to Black political and social activism. It is no secret that Black activism in institutions of higher education, particularly during the tumultuous decades from the 1950s through the 1970s, catalyzed new freedom struggles and enhanced the intellectual development of African Diaspora Studies in educational spaces. Yet, the activism of K-12 educators in public schools receives too little attention. While some education scholars have documented Black teachers’ activism since the late eighteenth century, public school teachers deserve broader recognition within Black activism historiography.

From the late nineteenth century through the present, parallel movements shaped teachers’ activism: the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education ruling to desegregate schools, Civil Rights and Black Power struggles, and the burgeoning women’s movement. Against this backdrop, Black teachers served as recruiting agents for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Civil Rights movement. They also called for schools to uphold the promises of desegregation, actually integrating schools and reforming school finance through more equitable allocation of resources.

Inspired by the campus movements of the sixties, the collective efforts of K-12 educators, students, and parents at Berkeley High School, for example, led to the development of the first Black Studies department in 1969. Despite this early move to diversify the K-12 curriculum, its legacy remains in flux. Today, many teachers are front-line activists fighting for the constitutionality of African American history and ethnic studies courses in public schools. And still intellectual activism and activist scholarship is often misperceived as a project only for academics, though Black teachers in K-12 settings have long embraced these pursuits. In fact, several scholars point to a strong lineage of sociopolitical activism in education. This scholarship highlights vanguards such as Anna Julia Cooper, Carter G. Woodson, Alain LeRoy Locke, and Sylvia Wynter—Black intellectuals who receive too little credit for advancing curricular theory.

Anna Julia Cooper’s work as a teacher, leader, and innovator at M Street High School, later known as Dunbar High School in Washington, DC, encouraged Black educators to view their role not only as teachers, but also as intellectuals. Cooper’s contribution to M Street helped establish the school as a premier educational institution, boasting notable faculty and alumnae. Omissions of teachers’ intellectual activism are particularly damaging to Black educators who—without these role models—fail to recognize the broader contributions of Black scholars and educators in the social and political history of schooling in the US.

As the largest professional occupation in the US, teaching accounts for the most professional employees among college-educated white women, Black women, and Black men. While the profession is well received, most teachers receive too little credit for their efforts. Critical education scholars challenge the notion that teaching is an apolitical enterprise. Scholars such as Paulo Freire and Gloria Ladson-Billings argue that teaching is in itself a political act because education is inherently political.

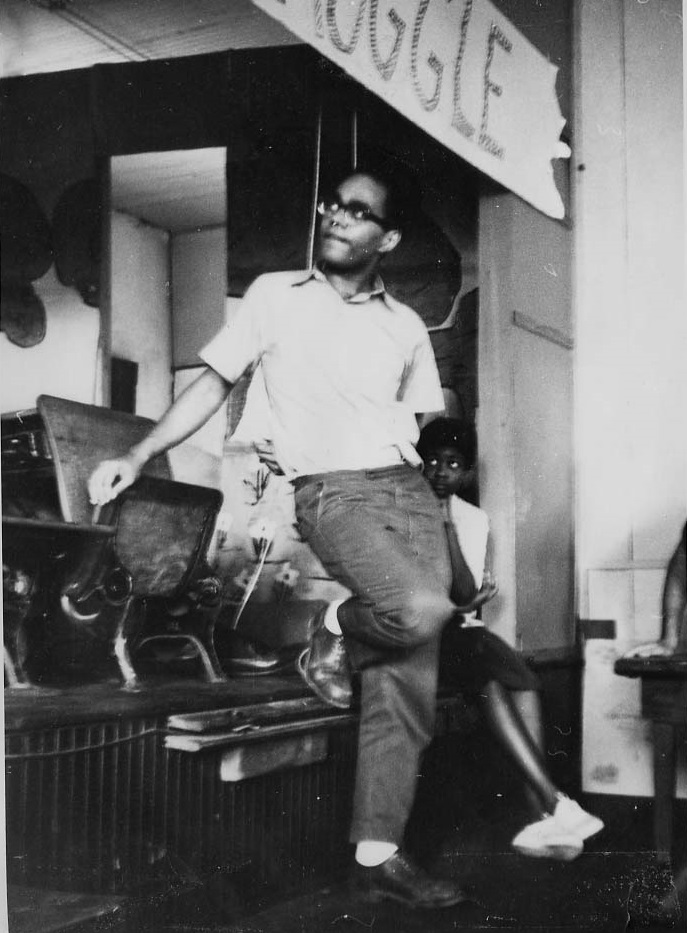

Beyond this conceptualization, the teacher-as-activist is also an identity and a consciousness one comes to assume, characterized by explicit social and political orientations against racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism, and classism. For Bob Moses, an educator and Civil Rights leader, his vision for economic and political freedom connects intricately with education: “When I was in Mississippi [in the 1960s], I saw very graphically how literacy mattered. Sharecroppers weren’t literate, so they were outside the economic arrangement. That’s what’s happening now in the inner cities. We’re growing young people who are outside the economic arrangements for the information-age technologies.”

Despite the commitment that teachers make to educate children, not all teachers are activists. Understanding when and where teachers enter activism begins with recognizing that public schools are social institutions rife with contradictions. As critical sites for socialization, schools reify dominant perspectives of anti-blackness, heteropatriarchy, Eurocentrism, and religiosity, often while providing a public good of “assimilationist” democracy.

A prominent example of this tension emerges from the historical and legal scholarship on school segregation and its impact on the teacher labor market. For example, teacher activists and researchers recounting teacher segregation in Chicago highlight discriminatory labor policies that subjected Black teachers to be newly classified as Full Time Basis Substitutes (FTBs). Despite doing the same work, this distinction amounted to different wages and benefits than white teachers received. Over the course of two years in 1967 and 1968, an organization called Concerned FTBs led more than a hundred schools in a strike against institutional and procedural racism and school segregation.

These histories reveal how societal tensions give rise to Black teacher activism. Even contemporary movements, such as Black Lives Matter, illustrate symbiotic relationships amongst movements, activism, and education. The Movement for Black Lives, a coalition of organizations demanding an end to state-sanctioned violence, considers public schooling a form of the state’s violent apparatus. With numerous policy initiatives addressing federal, state, and local inequities in school funding, excessive discipline and policing in schools, and the neo-liberalization of public schools—teacher activism is inevitable.

As a result of neoliberalism’s assault on Black youth and educators (i.e., closed schools, loss of Black anchor institutions, as well as the displacement of Black teachers), teachers have grown increasingly politicized. In May 2016 more than 1,500 teachers called in sick at 94 of Detroit’s 97 public schools. Similar activities repeated across the country in school districts in Chicago, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles. These massive protests or “sickouts” targeted many of the same practices waged in the aftermath of the 1954 ruling.

Beyond public demonstrations, forms of Black teacher activism consistently take shape inside the classroom through teaching and learning. These acts generally remain unnoticed and seldom catalyze the masses. However, many teachers express their activism through pedagogy, whereby texts become tactics. In this view, teaching-as-activism is indispensable to Black intellectual and activist scholarship. Teacher activists critique power, encourage intellectual curiosity, deepen self-identity and consciousness, and strive to make history culturally relevant for students.

Nevertheless, positioning teacher activism in this broader canon requires a degree of rupture. We must first acknowledge the traditions of teacher activism that enabled Black teachers, especially Black women, to “uplift the race, develop the community, gain for it the more equitable place in society it deserved, while creating for themselves important positions of leadership.” Second, we must recognize that teaching in schools does indeed “constitute legitimate and necessary forms of activist strategies.” This reconceptualization of activism parallels Black youths’ new age activism in the twenty-first century. At a time when there is a dire need to recruit and retain more teachers of color in the workforce, recognizing the activist work of K-12 educators is vital.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

An article that’s needed to share with parents & those working on justice in education.