Teaching Religion, Politics, and Civil Rights

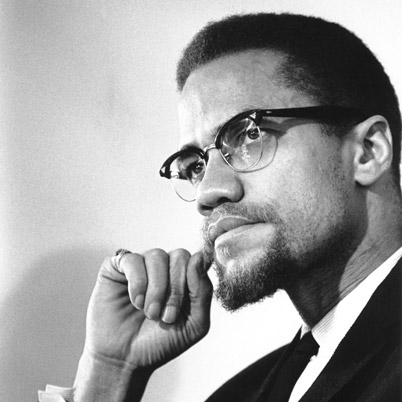

With undergraduates I recently explored the complexity of thought among several Civil Rights writers and activists. During our conversation, students rethought the meaning of terms like radical, conservative, and moderate and they reflected on how we define religion and politics as either separate or related modes of analysis. Students had to prepare for discussion by briefing comparing the mid 1960’s views of Malcolm X, James Baldwin, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Joseph H. Jackson. Most students easily compared Martin and Malcolm, and some others added Joseph to this mix. Virtually all the students knew of Malcolm and Martin, but none knew of Joseph H. Jackson, and those who knew of Baldwin had not been introduced to him as a Civil Rights writer.

Even after an introductory lecture where I stressed some of the differences between these activists, many students argued that all of these writers were more similar than different; they were all black, they were all male, and they all had mostly the same goals when it came matters of racial freedom and equality. Furthermore, students explained that Malcolm was more radical than Martin. When I asked students if these writers agreed on the timing and the rate of social change for equality, they began to make comparisons they had not made before. Students took a closer comparative look at Joseph H. Jackson’s From Protest to Production (1962) speech to the National Baptist Convention and Martin Luther King’s Letter From a Birmingham Jail (1963). Investigating these two documents allowed students to recognize that although King and Jackson were both prominent Baptists their theological differences were subtle but lead to significant political differences.

Moreover, for the students, this pairing added a new dimension to the usual critics brought to bear in discussing the various motivating ideologies underlying the Civil Rights movement and its immediate results. When comparing Jackson and King, students no longer easily thought of King as a kind of accommodationist in comparison to Malcolm. Viewed from the perspective of Jackson, Martin and Malcolm became more similar in how they defined and argued for civil rights. Most importantly, students began to understand how the vague categories of “radical” and “conservative” obscure important nuances of similarity and difference concerning ideas of theology, community, and social change.

We also watched Muhammad Ali (Cassius Clay) to discuss further how the labels of radical and conservative only reify problematic presumptions about religion and politics during the Civil Rights era. I explained to students that a previous generation of scholars first thought about Black Muslims and the Nation of Islam as expressions of political thought rather than religious belief. I was not surprised to find that some students initially found this interpretation reasonable. What is at stake are a set of presumptions about Islam and about religious belief. Students presume that Islam is something that is less about religion and more about politics, and that religious belief arises from concerns for peace, harmony, and reconciliation instead of from strife, disagreement, and inequality. All the students know Muhammad Ali and they tend not to think of him as a radical figure. When I explain all that Ali lost by refusing to enter the draft because of his religious belief, students begin to rethink their prior contrasting of religion and politics. Ali knowingly sacrificed a significant part of his career for religious belief. Ali and the Nation of Islam understood that the rest of America viewed their religious choices through a political lens. It is important that the students also make this distinction so that they can understand how religious belief and political ideology inform and infuse each other.

We also read excerpts from James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time (1963). Baldwin provides yet another useful perspective from the 1960s that further allows students to rotate Civil Rights writers in an ideological kaleidoscope where the meaning of terms like radical and conservative changes and where these terms cannot elide historical and theological specificity. Baldwin introduces a mode of analysis that many students did not expect.

Baldwin wrote critically of the Nation of Islam, but he also provided perspective on their uniqueness and attractiveness for growing numbers of African Americans. Baldwin, like King, believed that the United States might fully reconcile itself with its racist past, yet unlike King, Jackson, and Malcolm, Baldwin was willing to consider God as an idea, a construction. Baldwin emphasized the colonial legacy of Christianity:

“Christianity has operated with an unmitigated arrogance and cruelty — necessarily, since a religion ordinarily imposes on those who have discovered the true faith the spiritual duty of liberating the infidels.”1

Here Baldwin partially echoed Malcolm X, yet unlike Malcolm, Baldwin was willing to let go of God:

“If the concept of God has any validity or any use, it can only be to make us larger, freer, and more loving. If God cannot do this, then it is time we got rid of Him.”2

Baldwin revealed the depths to which Pentecostal Christianity framed his personhood in his majestic and powerful novel of ten years earlier, Go Tell It On the Mountain (1952). Yet, even in Go Tell It On the Mountain, Baldwin revealed the paradox of a conversion that sanctified the 14 year old protagonist, John Grimes, but that did not draw out his father’s love and that probably led John away from ever understanding himself as being gay. Baldwin makes this question about religion explicit in The Fire Next Time. He raises important issues about the relationship of religious practice and belief to self-affirmation and to activism.

This discussion leads students to recognize the complexities of religious and political thought within Civil Rights activism. However, students also ask what lessons they should take from the juxtaposition of these different and differing thinkers. My answer to this is not straightforward. As an historian, I am certainly comfortable explaining the past to my students; however, they sometimes ask me to help them unravel the present. I explain that we explore the ideological and political differences between black thinkers not to discount their ideas and strategies but to understand better how and why they came to believe what they believed. This becomes my answer. The past can give us vital perspective about the present, but we are building today together. Furthermore, like the thinkers we study, we should allow ourselves to imagine better futures.