Teaching Quilombismo: An Afro-Brazilian Political Philosophy

In 1980, Abdias do Nascimento, one of Brazil’s greatest black activists and intellectuals, published a seminal essay titled “Quilombismo: An Afro-Brazilian Political Alternative.” Based on his address to the Second Congress of African Culture in the Americas, the essay was a sweeping declaration of black rights, asserting “the urgent necessity of Black people to defend their survival and assure their very existence as human beings.”

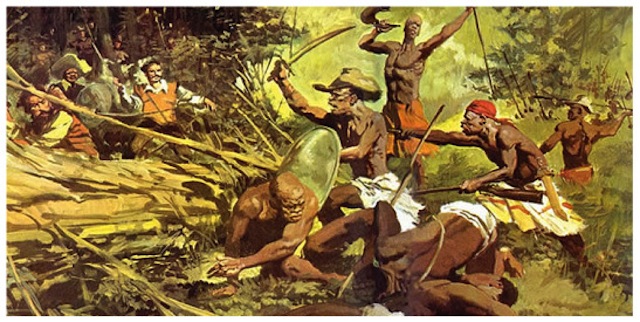

He strategically called this ideology “quilombismo,” a derivative of the term “quilombos,” which refers to the communities of escaped slaves in Brazil from the early 16th century to 1888. Similar communities with different names were found throughout the Americas: palenques, cimarrones, and maroons. Quilombismo, then, is an ideology based on an understanding of quilombos as historical beacons of democracy and equality. By offering an alternative to captivity, quilombos allowed Africans “to recover their liberty and human dignity” by organizing their own “viable free societies.”

Quilombismo is also based on an unusually broad understanding of quilombos, one that encompasses more than just remote communities of escapees. Nascimento includes any Afro-Brazilian cultural organization that provided a means of building community and facilitating African continuities, even those that were tolerated (or even encouraged) by the authorities: lay Catholic brotherhoods and sisterhoods, terreiros, afochés, and samba schools. All were “genuine focal points of physical as well as cultural resistance.” They were legalized quilombos.

In this way of thinking, a quilombo is not a relic of history but an ongoing, adaptable product of present circumstances. A quilombo is a model that “has remained active as an idea-force, a source of energy inspiring models of dynamic organization.” It is a heroic prototype of African-American liberatory activism, in a constant process of “revitalization and remodernization.”

Nascimento was an adamant pan-Africanist who believed that “black people have a collective project: the erection of a society founded on justice, equality and respect for all human beings; a society whose intrinsic nature makes economic or racial exploitation impossible.” Quilombismo is thus both a black movement and a humanist ideology.

It is African and universal, Brazilian and international. It is rests on the culture and struggle of black men and women around the world. It is radical in its call for communitarianism and its rejection of capitalism. It aims for the liberation of all human beings, sustaining “a radical solidarity with all peoples of the world who struggle against exploitation, oppression and poverty, as well as inequalities motivated by race, color, religion or ideology.”

This is a brilliant call to arms, a moving and powerful ideology of cultural reclamation, resistance, and transfiguration. It is a revolutionary manifesto, bold and unafraid, particular in its details and universal in its goals. It is vitally relevant to today’s struggles for full and equal humanity.

It is also flawed.

Quilombismo does not stand up to historical scrutiny. There are problems with the historicity of Nascimento’s ideology. For example, some of Nascimento’s premises about about black antiquity, pre-Columbian Afro-America, and Afro-Brazilian history have not held up. Scholars have largely rejected notions that Africans were present in the Americas long before Europeans arrived. Afro-Brazilians were not all, in fact, “literally expelled from the system of production as the country approached the ‘abolitionist’ date of May 13, 1888.” And the definition of favela is far more complicated than Nascimento’s simplistic description of “makeshift shanties of cardboard or sheet metal, perched precariously on steep, muddy hills or swamps” allows.

Then there is the most significant problem: that quilombismo is based on an idealized, mythical, ahistorical understanding of quilombos themselves. These communities of escaped slaves were not necessarily the bastions of freedom and communitarianism that Nascimento, like others in Brazil’s Black Movement, assumed (and continue to assume) them to be. Indeed, the largest, most iconic of them all—Palmares, a quilombo of twenty thousand people who resisted all state attempts to destroy it for nearly 100 years—was not an egalitarian society at all. It was hierarchical. It was organized not by democratic but by tributary and kinship relations, along modes of the Central African states from which many of its first residents originated.

Nor was it entirely black and entirely free. As Robert Nelson Anderson has argued, while many of the founding residents were born in Angola, over time Palmares became a multi-ethnic and largely creole community, with most palmarinos having been born in Brazil of African descent. The community included enslaved people, displaced Portuguese and Dutch colonists, and impoverished immigrants of various racial backgrounds. It was not only an alternative society for Africans and Afro-Brazilians; it was an alternative to the colonial state for any who wished to reject it.

So here we come face to face with what Africanist Luise White, in another context, has called the difference between historical fact and social truth. Quilombismo is an ideology based more on the myth of quilombos than on their historical realities. What we today believe Palmares to have been is not, in fact, what it was.

What do we do with this as scholars, teachers, writers and activists? How do we confront an ideology that is historically problematic at the same time that it is politically powerful?

I believe we can do this by not discrediting Nascimento’s vision. We can recognize its errors while celebrating its purpose. We acknowledge what is true and we challenge what is not. And we raise questions—useful, generative questions—about the ways in which history is used for political purposes, by whom, and how. Indeed, one of the most fascinating aspects of his groundbreaking ideology is that it celebrates a history that is more legend than fact and that yet, in spite of this, is a significant and powerful history.

Nascimento’s agenda was nationalist, pan-Africanist, and humanist. His sense of responsibility was for “the destinies and futures of the Black Africanist nation worldwide.” He used his understanding of history to advance his goals, imperfect though that understanding was. In considering his work, we can be both admiring and critical. We can use history to both interrogate and respect his ideas. Teaching “Quilombismo” is one way, at this critical moment, to support our students’ activism while also sharpening their acumen.

Laura Premack is a historian of Latin America and West Africa and an interdisciplinary scholar of religion, culture, and globalization. She is currently Assistant Professor of Latin American History at Keene State College. She is working on a book manuscript entitled, Atlantic Demonologies: A Spiritual Cartography. Follow her on Twitter @LauraPremack.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Intellectual warfare- Dr. Carrutherts is right on point.

There’s a significant contrast between myth and reality about the early American colonies and establishment of the country. It’s time we looked more carefully at that as well!!