Teaching Living History: Between the Living and the Dead

Fall is looming close, which means it is that time of the year when many of us are returning to the classroom. It is an especially chaotic time for academics as we gear up for the teaching work that accompanies the life of the mind. For many, that means course preparation, syllabus (re) fashioning, advising, and mourning the loss of a summer that was not nearly as productive as one might have hoped. For me, the beginning of a term is all of these things, but it is also a time to reflect on what went well and what went wrong the previous year, and to mull over what I want my students to take away from each of my classes. My own process ties those goals to course objectives stated succinctly in the syllabus, but it also entails a necessary inward turn to consider what I really want students to learn.

Earlier this month, Dan Berrett wrote “A Year of Racial Tumult Brings Potent Lessons—and Risks—to the Classroom,” [1] in which he described the ways that last year’s litany of “racially charged events” made for pedagogical interventions that were powerful and provocative, but also had potential pitfalls. The article, which featured insights from our fearless AAIHS leader Chris Cameron, spoke largely to the pedagogical choices teachers make and the challenges (and emotional exhaustion) that can accompany those choices. For those of us who teach about race (and gender, and sexuality, and religion), the simultaneous impact of reality and history are never too far removed as there is always some salient headline that can be incorporated as a teachable moment, and events affecting our every day lives have resounding relevance in the classroom space. The challenges of separating identity from ideology in one moment, while keeping students attentive to how identity and ideology intersect in ways that have lasting economic, political, social, and cultural implications in another, is something that we adeptly navigate. It has been interesting for me to watch that ways that the “racially charged events” Berrett discussed are being engaged in such highly publicized ways. For many of us, including Ferguson, BlackLivesMatter, the Charleston Nine, and other “heavy racial topics” was never just incorporated to enliven our courses, nor is it (or the potential emotional exhaustion that accompanies such topics) anything new. Rather, this is the work that goes on in our classrooms every day, and the general population is only now understanding what it is that we do.

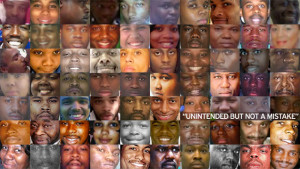

“Unintended But Not a Mistake”~image courtesy of Gawker[2]

As any teacher well knows, the risks of incorporating these moments can vary, as can student responses to them. Rather than shying away from those risks I tend to embrace them head on, and allow the events that shape our present to filter into our readings, assignments, and discussions. I tend not to worry about what may go right (or wrong). Even as I have a syllabus that I spend a great deal fretting over, my approach to teaching can be likened to improvisation. And, as any musician well knows, there are the risks of falling flat, but when done well, improv can take your music to another place. It involves trust and a willingness to be open in the space, and to allow what happens to literally just take you. Even as I write this sounds a bit romanticized, but as a teacher, it is true for me. Admittedly, I have a freedom to do that because I have learned the pedagogical patience that comes from experience and because I have the privilege of teaching at one of the most prestigious liberal arts colleges in the country, which supports and takes great pride in pedagogical innovation and its accompanying risks.

But I like to think that there is something else that has positioned me to do this work in this way. As a religionist and historian (not to be confused with a religious historian or a historian of religions), my scholarship forces me to consider the spaces where the living and the dead intersect.[3] This means that I spend a great deal of time thinking about how the living and the dead encounter each other through space, time, materials, genealogy, and events. I have learned that the living and the dead are never too far apart, even as the objectives of modern education might suggest that we suppress those connections. The recent events surrounding the death of Sandra Bland and the accompanying twitter activist intervention #sayhername harken to historical events of a not-so-distant past, and are indicative of those connections. The dead are now called upon to give witness to and remind us of the deep costs of devaluing black lives. These moments remind us that the dead remain present with us.

So as summer comes to an all too swift end, there is a part of me that hopes that my classroom this fall will not be overwhelmed by additional events indicative of this seemingly racially tumultuous climate. There has, after all, been enough “data” over the past five years to modify an entire curriculum. That said, however, I am also optimistic about continuing to consider the ways in which the living and the dead speak to and inform each other. I want my students to recognize that those spaces between the living and the dead are never as far removed as we like to think, and that the rewards of teaching living history are always worth the risk.

[1] The Chronicle of Higher Education. August 7, 2015.

[2] http://gawker.com/unarmed-people-of-color-killed-by-police-1999-2014-1666672349

[3] Talking to the Dead: Religion, Music and Lived Memory among Gullah/Geechee Women (Duke University Press, 2014).

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

First off I would like to say awesome blog! I had a quick question which I’d like to ask if you do not mind. I was interested to know how you center yourself and clear your mind prior to writing. I have had a hard time clearing my mind in getting my thoughts out. I do take pleasure in writing but it just seems like the first 10 to 15 minutes are wasted simply just trying to figure out how to begin. Any ideas or tips? Appreciate it!|

Hey There. I discovered your blog the usage of msn. That is a very smartly written article. I’ll make sure to bookmark it and come back to learn more of your helpful information. Thanks for the post. I will certainly return.

After reading your articles i became very keen follower you..