Stuart Hall: “Familiar Stranger” of the Black Atlantic

Stuart Hall’s posthumous memoir, Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands, is the most recent entry in his eponymous book series at Duke University Press. Written with Bill Schwarz, Familiar Stranger is not a memoir in any formal sense, but an examination of “the connections between ‘a life’ and ‘ideas’” (10). Hall uses his life and ideas to trace his trajectory from Jamaica to England; colony to metropole, and from the margins to the center of the colonial experience. His emigration movement mirrored a generation of Black exiles struggling to make sense of their identities and sense of “home.” Familiar Stranger is an insightful recollection into the “connections and dissonances” of belonging between two islands. Hall and Schwarz explore the ways in which Black imperial subjects, like Hall, occupy a liminal and complex place of belonging, in the Caribbean or England. This situates the recent attacks on the Windrush generation—those who migrated from the Anglo-Caribbean to England between 1948 and 1971—into historical context. Hall is a part of this Black emigrant movement and the colonial experiences that have engendered feeling like a “familiar stranger” of the Black Atlantic.

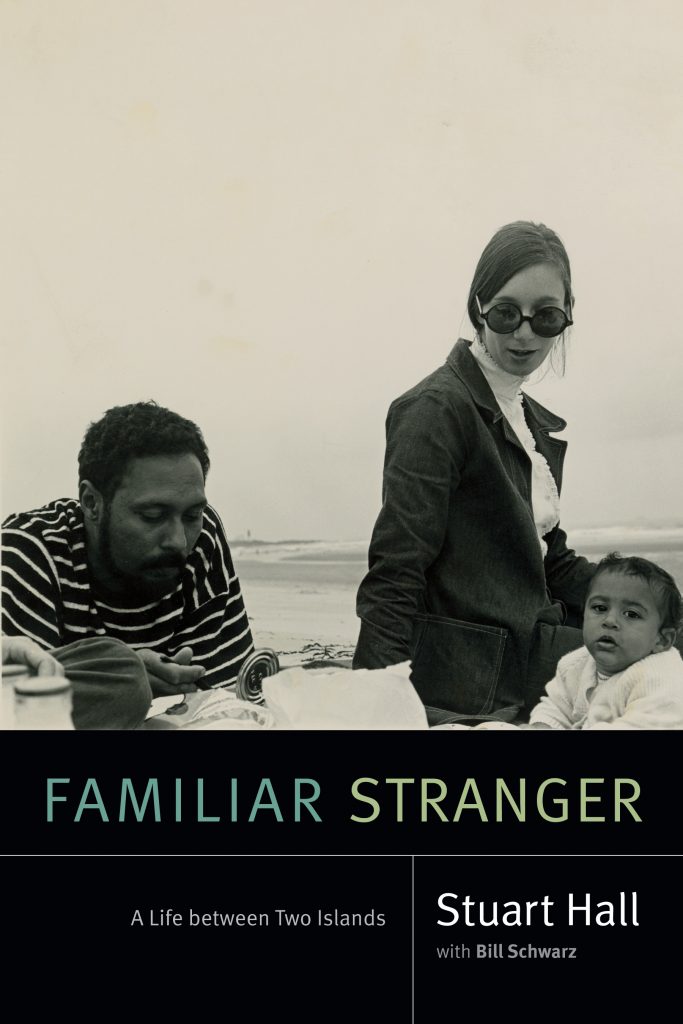

Published in 2017, three years after Hall’s passing, Hall and Schwarz created a massive manuscript compiled over the past twenty years. Through shared conversations, memories, speeches, interviews, personal photographs and annotations, Familiar Stranger takes readers on the journey of Hall’s life: from his coming of age in 1930s Jamaica, his migration to England as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University during the 1950s and ends with his decision to stay in London and pursue a career as an activist, educator, and scholar during the 1960s. This scholarly yet intimate recollection of Hall’s life is divided into four parts: “Jamaica,” “Leaving Jamaica,” “Journey to an Illusion,” and “Transition Zone,” with topics ranging from colonial subjects, race, identity, Caribbean migration, modernity, and politics. Beginning with a preface written by Schwarz, nine essays chronologically follow this timeline, culminating with an extensive citation of writers from Andrea Levy to Eric Williams that have informed Hall’s ideas throughout the book. With that in mind, Familiar Stranger offers a profound portrait of Hall’s intellectual and personal growth during his most formative years as a colonial subject and an emigrant, as well as his insightful ruminations looking back on the complexities of his identities and sense of British imperial belonging.

Familiar Stranger grapples with the contested places of Blackness in Europe; postcolonial studies within the Black Atlantic; and race and identity in British historiography. Hall frequently cites scholars like Frantz Fanon, Paul Gilroy and Tina Campt who used ideas of race, gender, nationality and culture to examine a place of belonging for black folk in Europe and the Atlantic world. He also places Caribbean thinkers such as C.L.R. James, George Lamming, and Kamau (Edward) Brathwaite into dialogue with the work of Edward Thompson, Michel Foucault, and Eric Hobsbawm. This urges readers familiar with ideas about modernity centered with white male voices, to consider and engage with a wider range of perspectives including those from the Black Diaspora. Familiar Stranger also builds on a long tradition of Caribbean and African intellectuals like George Lamming, Chinua Achebe, or Edward Said who used their memoirs to document the “perilous exercise” of colonialism, utilized texts and theories from other scholars, and challenged different forms of gatekeeping through a multidisciplinary approach. Hall acknowledges that Familiar Stranger was not the first work to tackle the “perilous exercise” of a colonial perspective through a first-person account. Lamming’s The Pleasures of Exile, which mapped out the “late colonial migration” from the Caribbean periphery to the English metropole in 1960, was written during Lamming’s self-imposed exile in Great Britain (12). Chinua Achebe’s memoir exposed the colonial subject’s complicated relationship with the British passport where materiality of belonging granted entry, but not full and equal access to British culture and society for Black British subjects. Familiar Stranger shows that these and other colonial voices are critical to better understanding the praxis of being racialized as a perpetual outsider to the British experience.

This book builds upon recent scholarship on Black Europe and growing interest in situating Black British experiences. Historian Marc Matera’s Black London: The Imperial Metropolis and Decolonization in the Twentieth Century looks at how London became the nexus of Black internationalism and anticolonialism during the twentieth century. Matera demonstrates that in the 1940s, an “unprecedented number of female students” arrived in England from West Africa and the Caribbean. This was a similar migration route that Hall undertook when he won his Rhodes Scholarship to pursue an undergraduate degree at Oxford University in 1951. Familiar Stranger also complements the work of Kennetta Hammond Perry’s London is the Place for Me: Black Britons, Citizenship and the Politics of Race, which illustrates how Black Britons from the Caribbean became political actors in the metropole through negotiations of citizenship, race, and resistance. Perry centered blackness as fraught belonging in the metropole, and like Hall, disrupted the cultural amnesia and historical narrative of a completely white British nation and citizenship. Matera and Perry’s respective contributions give an historiographical depth and perspective to better consider the agency of Afro-Caribbean figures like Stuart Hall. Although his scholarly impact and legacy is profound, Hall is among the many Black Britons who lived within a British imperial world and confronted the challenges of personhood as British subjects, citizens, and people of the Black Diaspora.

Familiar Stranger is a fascinating meditation on the ontologies and isolations of being placed and displaced at the same time, offering a unique prism to interrogate the continued relevance and significance of racialized identities and colonial experiences. In the first sentence of the book’s the first essay, Hall states, “sometimes I feel I was the last colonial” (3). Born in 1932 and leaving Jamaica for England in 1951, Hall arrived in the metropole well before the formation of the West Indies Federation in 1958, and Jamaica’s independence in 1962. And yet, while Hall remained permanently in England after leaving his graduate program at Oxford without graduating in 1958, he did not feel like a British citizen. This uncomfortable feeling of displacement followed Hall throughout his life and the chapters of this book. He admits that “finding one’s place, socially and subjectively, in the complex world of the colony was a perilous exercise” (20). Although, Hall was born and raised in a British colony, his migration and settlement in Great Britain was fraught with tensions of racism, discrimination and displacement. One of the most insightful elements of Familiar Stranger is Hall’s ideas about race and identity formation over space and time. Like for many other Black people throughout the Diaspora, there is a point of reckoning with self through engagement with the other. Hall would have experienced W.E.B. Du Bois’ “double consciousness”—this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. This necessitates a constant shifting between identities, as opposed to a singular static notion of consciousness. In his adolescence, Hall understood himself to be “brown” or from a middle-class mixed-race Jamaican family. However, it was not until after arriving in England during the fifties that Hall claimed “blackness” as a personal identity, inspired by decolonization of African and Caribbean territories, African American social movements, and Black resistance politics in 1970s Britain (16). For colonial subjects inside and outside of the British metropole, Hall invoked the idea of the “diasporic” as a substitute for self-identity, in order to challenge the idea of “whole, integral, traditionally, unchanging, cultural identities” (144). By identifying as a part of the wider Black Diaspora, Hall subverted the racialized subjecthood of the British Empire, and transformed himself into a person who understood the power within articulating self-actualizing agency. Ultimately, creating self within diasporic Blackness allows the reconstruction of a discursive form of freedom and citizenship beyond the British metropole.

An undeniable boon to cultural and postcolonial studies, Stuart Hall and Bill Schwarz’s Familiar Stranger turns the traditional memoir on its head, and produced an engaging exchange about race, identity, colonialism, and culture. While this is a memoir about Stuart Hall, Familiar Stranger inspires a question on what this “perilous exercise” would be like for Black Caribbean women existing as colonial subjects moving between two islands. Familiar Stranger also disrupts the historical narrative of a benevolent Britain ostensibly offering Afro-Caribbean people opportunities for education and socio-economic advancement. This acknowledgment of the Windrush’s social, political, and intellectual contributions also serves as a reminder to those attempting to erase, remove, or marginalize Black Britons that were never deemed strangers when their help was needed. Over time, Black Britons, like Hall, became quite familiar with the liminal space of homelessness under a flag that claimed to not know their subjects by race, colour, or creed. Present-day challenges in confronting this shallow promise are not new. They are timely reminders of a British imperial world premised on the benevolence of imperial agents and citizens as they purportedly tried to civilize the Black colonial subjects. The laden violence of this civilising mission is that it allowed English people to revel in the superiority of their whiteness by conveniently ignoring how their pernicious anti-Black racisms illustrated the absence of their own civility. Ultimately, this book invites us to consider the power of a collective familiarity within experiences of being seen as unfamiliar.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.