Struggle and Progress: A Framework for African American History

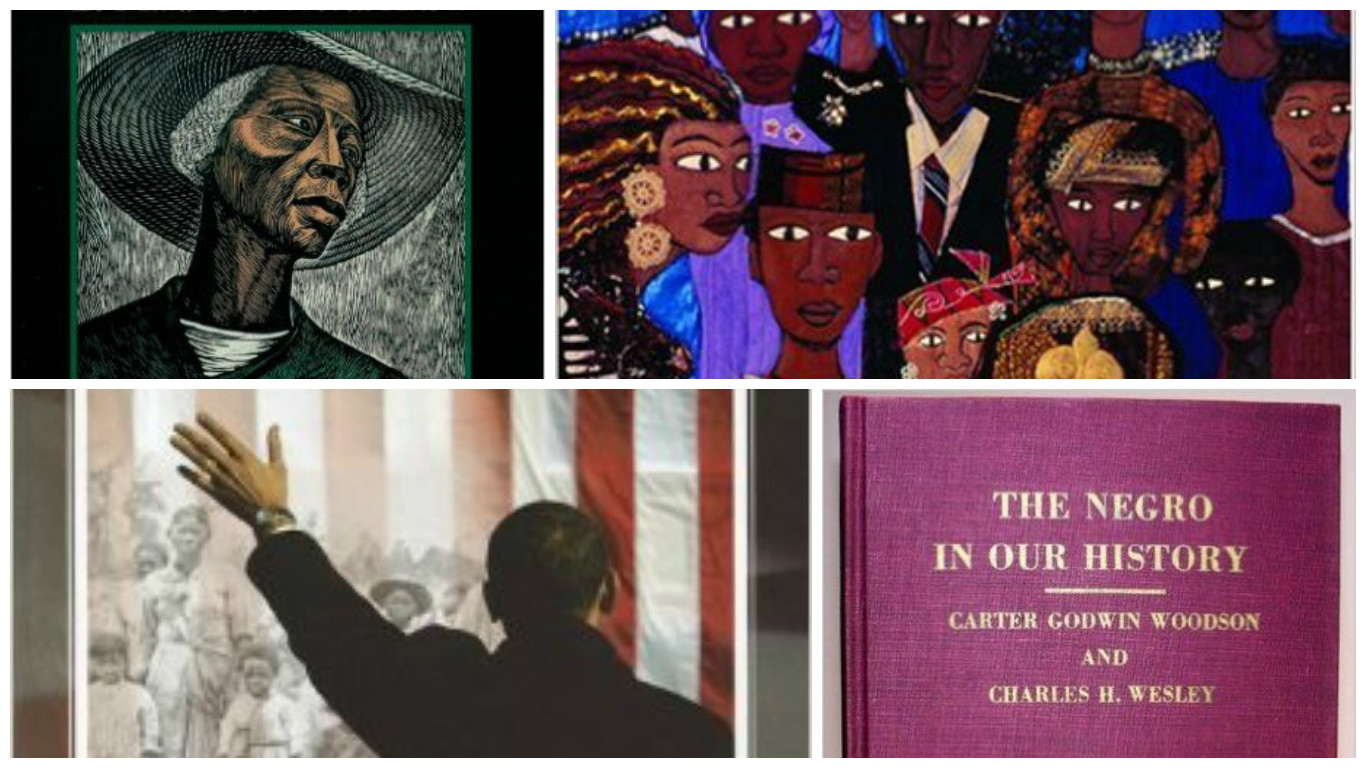

(Four books that synthesize African American history: To Make Our World Anew, edited by Robin D. G. Kelley and Earl Lewis; a later edition of Carter G. Woodson’s The Negro in Our History, with co-author Charles Wesley; Nell Painter’s, Creating Black Americans; and the ninth edition of John Hope Franklin’s From Slavery to Freedom, with co-author Evelyn Brooks Higgenbotham.)

With racism, violence, class struggle, and xenophobia so omnipresent in contemporary times, Americans, especially Black Americans, cannot help but wonder what, if any, social progress the nation has made.

Michelle Alexander, and others, raised awareness about how, during a supposed age of colorblindness, mass incarceration created a racial caste system like the one that controlled social, economic and political life during Jim Crow segregation.

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s recent book, From #Blacklivesmatter to Black Liberation, takes the commonplace question – can America still be racist with a Black man as President – and argues persuasively that, not only does racism continue during the Age of Obama, but it actually worsens. Levels of segregation, underdevelopment, and disparity in everything, from housing to education to employment to policing, shows how, for the group as a whole, over the past thirty-five years, Black people’s progress has remained stagnant and even deteriorated.

Patrick Rael and others have also pointed out the backward movement on voting rights. The arguments Republicans raised to make it harder for Black people to vote in 2014 do not sound dissimilar from the arguments white supremacists raised to deny Black citizens the franchise in 1914.

Historians may look back on the Age of Obama as a time that echoed an observation made by the abolitionist-turned-Union officer Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who, during the early dark years of Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction policies, noted “Revolutions can go backwards.”

One cannot deny that certain Black individuals have experienced progress in the form of money, fame, power and prestige. Barak Obama is the most visible example, but examples of Black progress exist in nearly every corner of American society.

This is not new. Throughout African American history Black individuals who prospered existed alongside Black people who perished. Indeed, the successful few appear as a shifting shoreline that rests against an expansive ocean of Black struggle.

Given these glaring contradictions, how should historians strive to write synthesis histories of who Black Americans have been, over time, in America and the world?

Over the past one hundred thirty four years, numerous writers have taken up the challenge of producing a narrative synthesis of African American history.

Carter G. Woodson’s approach in the 1920s was to examine, “The Negro in Our History.”

The narrative arc went “From Slavery to Freedom” for John Hope Franklin.

Vincent Harding used the metaphor of a river to narrate the history of “The Black Struggle for Freedom in America.”

Darlene Clark Hine and her co-authors saw the Black past as an “Odyssey;” and Robin D. G. Kelley and Earl Lewis collected essays that showed how generations of Black people worked “To Make Our World Anew.”

For Nell Irvin Painter, African American History and its Meaning is best understood through the “Creating,” especially the artistic creating, that Black Americans did over time.

These books make excellent contributions, but what will the current generation’s synthesis of the Black past look like? How should historians living through our contradictory age tell the history of Black Americans?

The ongoing relationship between “struggle” and “progress,” offers a clear window through which to see our past and to think critically and complexly about our paradoxical present.

While Black history is filled with many different narratives of struggle, far too often, despite all we know about the half-steps, counter-revolutions, backlash, bigotry, intra-racial class conflicts, misogyny, backward movements, and regression, the relationship between struggle and progress appears linear and inevitable.

We seem stuck in a history in which slavery leads to freedom, and freedom, contested though it may be, represents an end point in a journey our ancestors (and the nation) traveled. Struggle moves along a path from one stage to another. When revolutions go backward, when contradictory examples of progress and peril appear side-by-side, our histories fall short in helping us understand how we arrived at this point and condition.

We can see a historical fixation with progress as inevitable, and history as ever hopeful in many pieces of wisdom, from our grandparents and great grandparents saying,

We ain’t what we out to be, we ain’t what we want to be, but thank God we ain’t what we used to be;

to our generation saying,

Rosa sat so Martin could walk; Martin walked so Barack could run; Barack ran so our children could fly.

Such neat narratives of linear progress should leave us dissatisfied.

How can we look at our contemporary world, with a handful of those Taylor called “black faces in high places,” offset by millions of other black faces in prison cages, and accept our history as a one-dimensional story in which hope springs eternal? Does a history that inevitably points to progress help us understand our current messes, or how some Black people experience progress, and others do not?

Examples of Black progress exist; but progress for the few does not signal a history of progress for the many.

Historically, Black struggles do not necessarily, or naturally produce progress. Nor should our histories.

Sometimes Black struggles fail, completely. Our histories need to show that.

At other times, Black struggles produce progress for some Black individuals, but leave others behind.

Some moments of struggle might secure progress for large majorities of African Americans, only to see that progress slowly erode and weaken.

While examples of progress are undeniable, the consistent part of Black history in America is struggle.

“If there is no struggle, there is no progress,” Frederick Douglass said in 1857.

One hundred years later, Ella Baker captured the relationship between struggle and progress best when she reminded us, “We who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes.”

Historically, Black people have always struggled because racism proves capable of changing and adapting and hiding in plain sight. The struggles continue. Our histories should reflect that truth even as we note change, improvement, and progress.

“Look for me in the whirlwind or the song of the storm,” Marcus Garvey said. “Look for me all around you.”

Black struggles and Black progress, indeed Black history, is like Garvey’s whirlwind: constantly circular, churning, unpredictable, kicking up dust, creating new paths while blocking others, always, always, always in motion.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Beautiful, brother. Well done.

Thank you, Russell.

I love the quote from Marcus Garvey! Struggle and the contradictions and the side-by-side failures with progress are noteworthy and true. And now? The age-old question persists: should we stay or should we go?

Blackness the Life and Times of an Unpopular People by Dr T. Nicole Shockley is also a great and easy read for those who want to understand the relationship between the past and present day status of African Americans.