State Surveillance of the Black Freedom Movement in Memphis

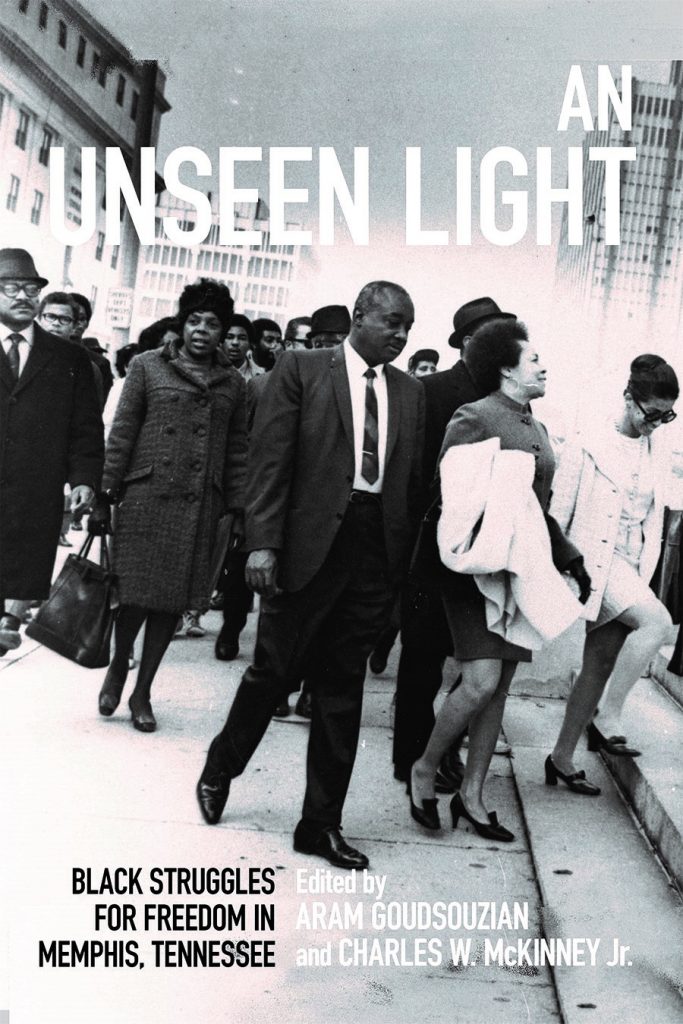

*This post is part of our online forum on Aram Goudsouzian and Charles McKinney’s An Unseen Light

On March 28, 1968, five thousand Memphians gathered to support Black sanitation workers demanding better wages, improved working conditions, and union recognition from their employer – the City of Memphis. With the help of local Black Power advocates “The Invaders,” local Methodist minister James M. Lawson, Jr. organized one of the largest anti-poverty marches ever held in the U.S. South. As the crowd of supporters grew larger, so too did the throngs of police surrounding them. The Memphis Police Department (MPD) was well aware of the intended march route, and they could easily pick out movement leadership in the crowd thanks in large part to a well-organized and federally backed Counterintelligence Operation (COINTELPRO) aimed at undermining so-called Black Extremists.

Armed with tear gas, batons, and shotguns, scores of MPD officers stationed themselves at key points along the march route. As the hot sun rose higher in the Memphis sky, the crowd waited anxiously for their guest of honor: Martin Luther King Jr. Arriving nearly an hour late, King was hurried into a car as bedlam unfolded in downtown Memphis. The march had proceeded only a few blocks before the sound of breaking glass shattered hopes of a nonviolent demonstration. Police chased the demonstrators back to their headquarters at Clayborn Temple, and fired tear gas into the historic Black church. One demonstrator, 18-year old Larry Payne, was killed when a police officer fired a shotgun into his stomach.

The events of March 28, 1968 – later called “Tough Thursday”- are well known to historians and popular audiences alike. But recently discovered FBI documents are reshaping explanations about why the march fell apart. In A Spy in Canaan, Marc Perrusquia explicates how Memphis’s famed civil rights photographer Ernest Withers served as an informant to the FBI for years. The fact that Withers spied on movement leaders is, in itself, not terribly surprising. Scholars and popular audiences have known for decades that the FBI spied on the movement, and people at the time were often well aware that surveillance was taking place.

However, in Memphis, the American city with the highest percentage of Black residents among the nation’s top twenty-five metro areas, the extent and depth of cooperation between local and federal police is only now becoming clearer. An FBI memo prepared by COINTELPRO special agents based in Memphis strongly suggests that one of their informants was at the center of the Memphis melee on March 28, 1968. COINTELPRO agents William Howell S. Lowe and William H. Lawrence interviewed James Elmore Phillips, Jr. on April 23, 1968, almost three weeks after the assassination of Martin Luther King in Memphis. The timing of the Phillips interview is odd since most interviews conducted by police about the assassination were completed by this time. An MPD officer with information about these processes has stated that it appears the only interviews these two COINTELPRO agents conducted were of informants.

Additional FBI reports indicate that Phillips, then a student at the historically Black LeMoyne-College, was a key facilitator in the window breaking on March 28 that brought long percolating tensions between white police and Black activists in Memphis to a boil. An informant recalled that on the day of the march, Phillips stated: They were going to “tear this SOB town up today.” Phillips made some general statements about some high school students being “chicken” and staying in school rather than marching and he stated that the white people who were participating in the march were fools for marching because if any trouble started that the Negro Marchers would turn on them first. An FBI report after the march confirmed the following:

Source two stated that the march started at approximately 11:39 a.m., and that Phillips and [Samuel] Carter [of LeMoyne College] and some unknown associates remained behind. As the March progressed north of Linden on Hernando, Phillips and another associate from LeMoyne College, understood to be in the [Black Organizing Project] BOP group, Clinton Ray Jameson, went back into an alley and obtained some sticks and bricks.

While it’s possible that FBI agents were attracted to Phillips only after observing his role in the events of March 28, what is clear is that by late April of 1968 Phillips was one of at least five movement activists providing information directly to COINTELPRO agents in Memphis.

These documents indicating collusion between local and federal police in surveilling the Memphis movement are significant for at least two reasons. First, the unraveling of King’s march in Memphis tarnished his reputation nationally and forced him to return to show that he could, in fact, still lead a nonviolent march. King was assassinated in Memphis on the eve of this second march. Second, some historians and contemporary observers have suggested that the failure of two distinct wings of the Memphis movement to work together contributed directly to the dissolution of the march. The thinking goes that the nonviolent wing under James Lawson’s leadership simply couldn’t corral the younger advocates organized through the Black Organizing Project (BOP).

I beg to differ. My research suggests that in the variegated milieu of Black politics in late 1960s Memphis, Black power advocates and nonviolent activists worked together through the War on Poverty. They established an alliance between these otherwise distinct factions of the movement. The explosive events of late March and early April 1968 are better explained, therefore, by two other factors: shared and dedicated political resistance by local and national officials to these Black-led anti-poverty efforts, and a robust and likely illegal effort by the FBI and local police to infiltrate and undermine both the Black power and nonviolent wings of the Black Freedom Movement.

This past summer, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) sued the City of Memphis for violating a 1978 consent decree that expressly prohibits “the City of Memphis from engaging in law enforcement activities which interfere with any person’s rights protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution including, but not limited to, the rights to communicate an idea or belief, to speak and dissent freely, to write and to publish, and to associate privately and publicly for any lawful purpose.”1 The decree was issued in 1978 following widespread, intrusive surveillance of activists involved both in anti-war and civil rights organizing activities. The decree made clear that the “the gathering, indexing, filing, maintenance, storage or dissemination of information, or any other investigative activity, relating to any person’s beliefs, opinions, associations or other exercise of First Amendment rights” was no longer acceptable.2 In short, collecting “political intelligence” on people not engaged in criminal activity was prohibited by law.

On August 10, 2018, Judge Jon McCalla ruled that the city of Memphis had in fact violated this 1978 consent decree by unlawfully collecting “political intelligence” on Black activists beginning in 2016 – efforts that likely flowed from a demonstration where activists closed the Interstate 40 bridge at Memphis. The ACLU furnished evidence that included a Joint Intelligence Briefing prepared by the Department of Homeland Security and the Memphis Police Department – a collaboration that harkens back to MPD’s joint efforts with the FBI in 1968. Memphis Police gathered intelligence on the Black Lives Matter movement by using false identities on social media: The ACLU trial has revealed that a Memphis Police Sergeant named Timothy Reynolds operated under the pseudonym “Bob Smith” to gather intelligence on Black demonstrators through Facebook. And on at least one occasion, Smith – who is white – falsely portrayed himself as “a man of color.” These jointly prepared intelligence briefings were shared with private citizens who worked at Memphis based AutoZone, a Fortune 500 company, and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, the sixth largest non-profit in the United States. The trial also revealed that the city maintains more than 1,000 surveillance cameras in public spaces.

The 2018 surveillance of Black activists in Memphis must be placed within this broader historical context. Since the early twentieth century, the United States has deployed the most sophisticated surveillance apparatus in the history of human civilization, and many of these technologies have been used for generations to monitor Black Americans and chill their freedom of expression. In both 1968 and 2018, Black Memphians were organizing to impact the major challenges they faced: poverty and police violence. These organizers were not criminals or engaged in criminal behavior, but they were surveilled as if they were. The criminalization of Black resistance not only deters free speech, it also encumbers the exercise of collective power by people engaged in naming and working to solve core problems facing their community. Such surveillance inhibits the unfettered exercise of collective, nonviolent power that has been used by people in the United States to influence the structural forces determining the context of their lives. Like much that happened in the City of Memphis during the twentieth century, the outcome of the twenty-first century ACLU trial will have significant implications for the lives of Black people in Memphis and beyond.