Starfish and Guerrilla Warfare: Marlon Riggs’s Tongues Untied at 30 Years

*This post is part of our online forum to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of Marlon Riggs’s groundbreaking film, Tongues Untied.

During a funeral scene in a recent episode of the television drama Pose, entitled “Never Knew Love Like This Before” (a nod to the R&B/Disco anthem originally made a commercial hit by singer and gay icon, Stephanie Mills), Candy’s ghost appears to Pray Tell who is presiding over her service. She was found stabbed to death in a seedy motel where she turned tricks to earn money to support herself and her “children” as Mother of a Ballroom House. Faced with limited opportunity, her choice against suffering is not an act of martyrdom but a gift of death, an act of non-transcendent faith and love. After declaring she forgives Pray Tell for how he treated her when she was alive, a mercy she believes was necessary for her survival as a dispossessed Black transgender woman, she asks why he refused to recognize her obvious beauty. With tears and some invective, he responds, “Maybe I didn’t want to look at you. You are unapologetic. Loud. Black. Femme. All the things I try to hide about myself when I go out into the real world. You are ALL of them. I guess, in a way, I was just trying to protect you.” She responds, “What good is everyone’s opinions when you’re gone …” Pray Tell admits that he was jealous of Candy’s “bravery.” She enlightens him. “I never had a choice to hide who I was. My loudness walked into the room before I did. Not a d*mn thing I could do about that.” And in a breath that releases Pray Tell of any guilt or shame for being a guarded Black gay man attempting to normalize himself in stigmatizing anOther, Candy assuages, “Maybe you’re just doing what you got to do to stay alive.”

Inextricably linked as Black Americans by a unique cultural heritage developed out of a racialized history of enslavement, apartheid, and institutional racism, Black transgender women and Black queer men suffer a common lived experience of catastrophe, albeit in different ways. Reconciliation between Black people is perpetually burdened by an intercommunal violence operating within neocolonial racism while imposing a heteropatriarchal order of corporeality and psychic desire in the regulation of race, gender, and sexuality in service to capitalism. Social contract liberalism is inherently fraught with the coercive violence between self-ownership as natural law and labor value determined by commodity capitalism. Free will, freedom of choice, foundational to the predetermined autonomous individual, then, encapsulates tautological death for Black subjectivity (always in proximity to commodified Blackness).

Refusing to play surrogate to a fantasized heteronormative Black masculinity like Pray Tell, to hide in her bravery or sacrifice her identity as if she could filter or edit out parts of her body, her experiences, her history — her loudness — Candy makes the choice to reject epistemological and ontological estrangement. Her survival as a Black transgender woman involves claiming the life-affirming and redemptive value of reconciliation through what Delores Williams refers to as the “ministerial vision of righting relations,” to deal with the cruel dehumanization and identity killing epistemologies of Christian theology and Cartesian metaphysics that uphold Empire and render Black women invisible and powerless. As Ibrahim Farajajé, formerly known as Elias Farajajé-Jones, argues, “the ultimate threat to heteropatriarchal fantasy,” the queer woman (whether cis-, transgender, or gender nonconforming) disrupts the private-public division by which legal violence in the liberal democratic tradition is constituted, invisibilized and reenacted in spectacular form as domestic or intercommunal violence (rape, transphobia, queer bashing, misogyny, heterosexism, racism, classism, etc.); it is for transgressing these boundaries that the violence is juridically upheld.1

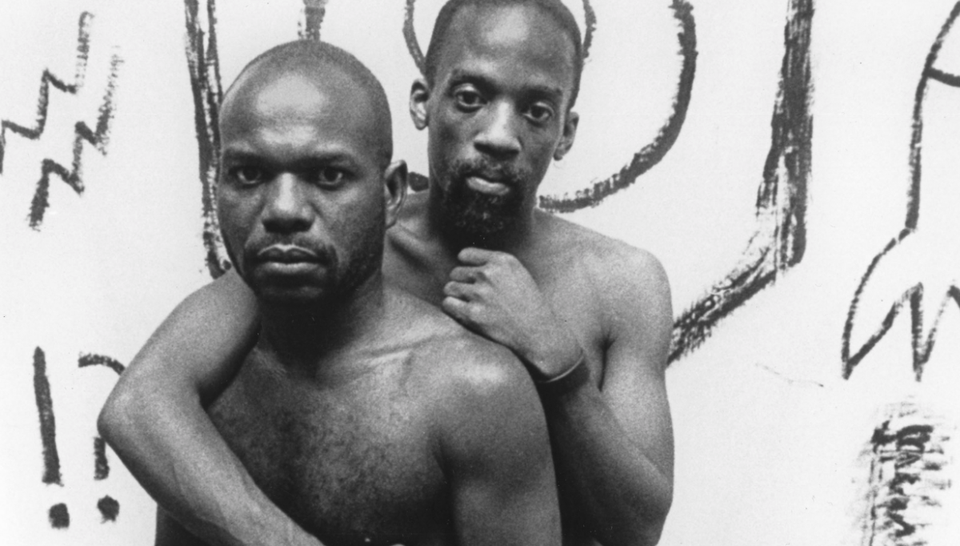

Tragically, only in memoriam does Candy’s “beloved community,” her chosen family, disavow fear and shame and embrace the complexities of Black queer existence and communitas, or what Stefano Harney and Fred Moten refer to as “undercommons,” a destructive orientation, fugitivity, predicated on difference that is concurrently sustaining and widening for future possibilities. This way of “dreaming in the open,” as Joseph Beam writes, is a survival strategy for living in-the-life of radical difference, an Otherness that disallows reductive identity and alienation to become permanent existence. Despite its obvious failures, Pose’s commemoration of Candy (a Black transgender woman sex-worker) is a move toward a radical Black queer “multiplicity” of becoming envisioned by Marlon Riggs’s Tongues Untied (1989) thirty years ago.

Riggs’s films, particularly Tongues, present what Gilles Deleuze might call minoritarian cinema, an assemblage of perceptual refraction occurring when one thinks and imagines in non-standardized language delimited by majority power. Tongues emerges through what Deleuze refers to as a “contamination” of poetry. This poetry, as James Baldwin argues, articulates the horror that is an epistemological war of exteriority, an existence outside the image of thought. In a cacophonous arrangement of divergent and conflicting subject/object relations, “intensities,” disrupting and re-ordering the sensory-motor circuitry perception regimes, Riggs affects a crisis in material structure along the actual/virtual axis of indiscernibility — the genesis of the dislocated, unknown body and unthought thought crystalized in the “time-image.” With each iterative utterance (at once) authoring agency and self-destruction, the Black/queer is already a poet. Reiterating Deleuze, Kara Keeling discloses, “The Black is a time-image … an interminable present” by which Black affective and bodily identity is constantly and continuously changing in relation to past projections of the Black imago. Oddly, Keeling’s study of the “black femme” shoreline of western thought does not consider Riggs’s cinematic work, which like her theory is indebted to Audre Lorde’s Black lesbian feminist, emancipatory conceptualization of poetry: to bring the unthinkable thought, the un-thought, into being — theorized in “Poetry Is Not A Luxury” and “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action,” a decade before Deleuze and Félix Guattari.

Because a generation of artists in the 1980’s and 90’s give life to Black queer cinematic images, even as many faced impending death due to the HIV/AIDS pandemic, a transformative art-activism erupts into what is only now the budding realization and incremental progress with a potential Black queer film, television, and web media industry. Riggs intended Tongues along with his short-films Affirmations (1990), Anthem (1991), and Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien/No Regret (1993) to unfix multiple schisms distorting Black queer life and contributing to the haunting silence surrounding disproportionate rates of death and destruction among Black Americans during an apocalyptic period of HIV/AIDS, multiple wars on drugs and crime, and a hyper expansion of the prison industrial complex and carceral state. However, for nearly two decades following the posthumous release of Riggs’s Black Is…Black Ain’t (1994), Ada Gay Griffin and Michelle Parkerson’s feature documentary, A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde (1995) and Cheryl Dunye’s feature romantic comedy, The Watermelon Woman (1996) — at the height of the pandemic and supposed New Queer Cinema propagating the message of queer tolerance (“We’re Here, We’re Queer, Get Used to it!”) — the media landscape was nearly devoid of images representing Black queer life. It is not until Rodney Evans’s drama revisioning Bruce Nugent and the Harlem Renaissance, Brother To Brother (2004); Patrick-Ian Polk’s groundbreaking but short-lived television series Noah’s Arc (2005-6); and Dee Rees’s breakout lesbian coming of age drama, Pariah (2011) that there is waning re-emergence of Black queer filmic images.

The alienation of Black queer desire from the cultural frame of popular media and public health education, which have largely been controlled by white gay and lesbian run neoliberal organizations, exploits the taboo of racialized sexuality undergirding a hegemony benefitting from biomedical discourse trafficking in vocabularies of colorblind ideology. In dealing with anti-discrimination law reforms defined by an integrationist standard of civil rights — to reproduce an equal protection rhetoric-absent analysis invested in how structural domination contributes to HIV/AIDS transmission — a distorted science upheld by research predicated on regulating individual pathology reinforces the privatization of disease as it induces public terror concerning Black sexual contagion. The normalization of a “queer paradigm” to fit into an already heteronormative government-regulatory biomedical/public health science apparatus organized around a universal risk behaviors concept further stigmatizes and alienates groups already pathologized because they are perceived as threats due to the high incidence of transmission among their communities (Blacks, youths of color, transgender, sex workers). The failure of the queer paradigm is evident in documentaries that revisit the early decades of HIV/AIDS, We Were Here (2011) and How To Survive A Plague (2012), which include next to no representations of Black/Latinx or transgender peoples.

At risk is society’s evaluation of life in its fragility, “that precariousness itself cannot be recognized,” writes Judith Butler. How have regulating apparatuses and aesthetic technologies — law, medicine, film, media — ordered the frame of loss by which these departed lives have gone unrecognized, discounted, misrepresented, misinterpreted, or altogether uninterpretable? How might we make the case for restorative justice? Tongues Untied is Riggs’s S-O-S to all Black/LGBTQIA+ peoples to end the silence of past deaths accumulated in present living and dying — to confront political alienation and psychic disorientation by “looking for the dead … looking for the AIDS dead now,” as Dagmawi Woubshet phrases it.

- My reading of Farajajé is informed by Sara Ahmed, Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality (New York: Routledge, 2000); and, Sandeep Bakshi, Suhraiya Jivraj, and Silvia Posocco (eds), Decolonizing Sexualities: Transnational Perspectives, Critical Interventions (Oxford: Counterpress, 2016). ↩